Yakuza Tattoos, often referred to as Irezumi, hold a mystique that extends far beyond their striking visual appeal. For many in the West, the image of a Japanese man adorned in a full-body tattoo immediately conjures thoughts of the Yakuza, Japan’s infamous organized crime syndicates. But the connection is far more nuanced and deeply rooted in Japanese culture, aesthetics, and a philosophy of hidden beauty. This exploration delves into the world of Yakuza tattoos, uncovering their history, symbolism, and the unique perspective that sets them apart from Western tattoo culture.

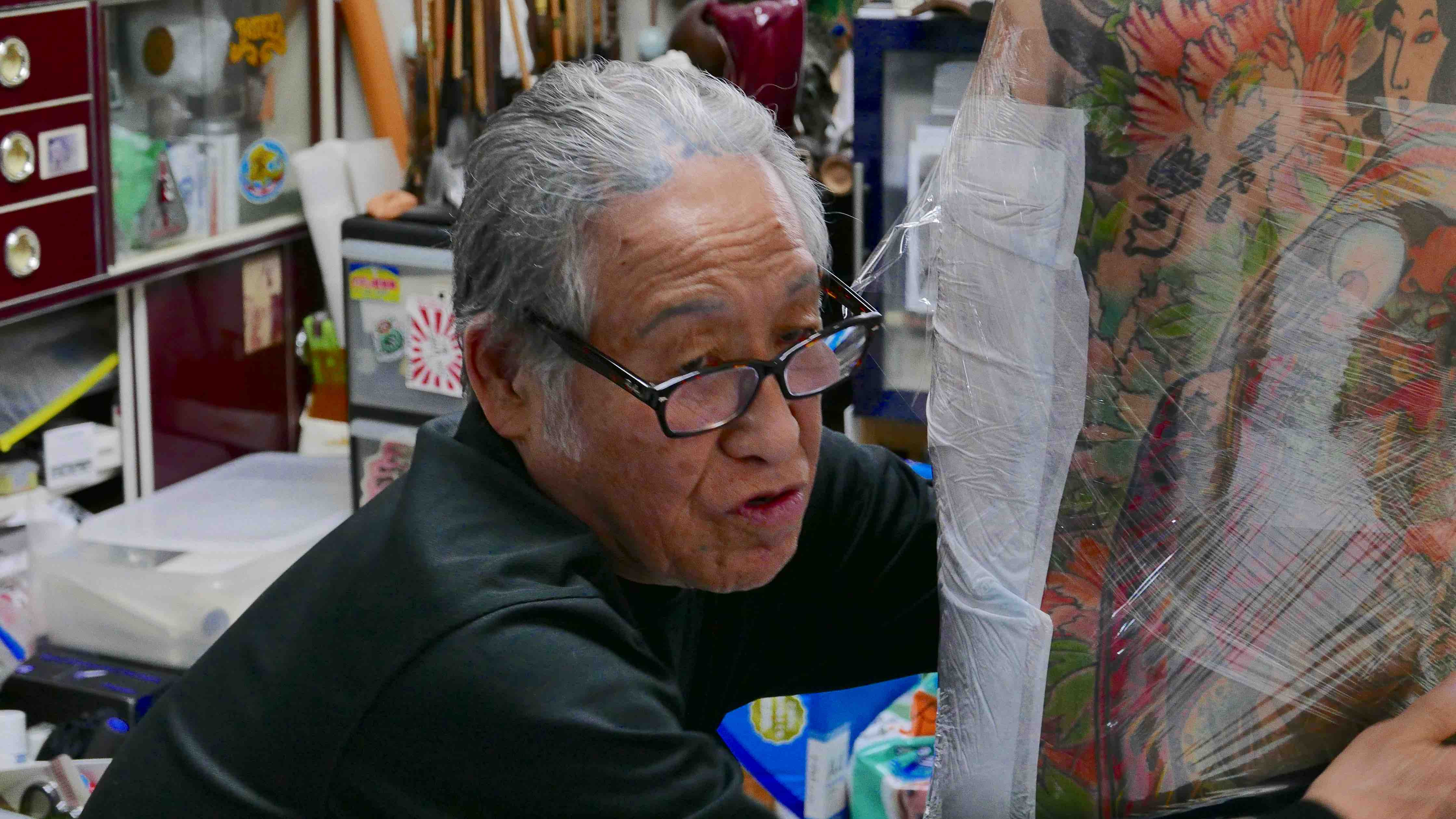

To truly understand Yakuza tattoos, it’s essential to move beyond superficial associations and delve into the heart of Japanese artistry and societal values. One figure who embodies this depth is Horiyoshi 3, a legendary Irezumi tattoo artist based in Yokohama and favored by many within the Yakuza. A visit to his studio, as described in a firsthand account, offers a glimpse into this hidden world. The atmosphere is not one of overt intimidation but of quiet dedication to craft. Even surrounded by Yakuza members, the focus is on the meticulous art of tattooing, a process that demands patience and respect.

The Yakuza and the Allure of First-Class Art

Why do Yakuza members seek out artists like Horiyoshi 3? According to Horiyoshi himself, it’s a matter of pride and a pursuit of the best. Yakuza are known for their commitment to quality in all aspects of their lives – from their attire and social circles to their vehicles. This extends to their tattoos. They seek out the finest Irezumi artists because their tattoos are not merely decorations but profound statements of personal identity and strength.

The association between Yakuza and full-body tattoos is undeniable in the Western imagination, often fueled by media portrayals. However, Horiyoshi offers a different perspective, emphasizing the positive, albeit often unseen, contributions of the Yakuza to their communities. He points out their rapid response and aid during natural disasters, highlighting a code of conduct that extends beyond the criminal stereotype.

A young member of the Yakuza patiently undergoing a traditional Japanese tattoo session, highlighting the dedication to Irezumi.

A young member of the Yakuza patiently undergoing a traditional Japanese tattoo session, highlighting the dedication to Irezumi.

Historical Roots and Symbolism Beyond Crime

While the connection to the criminal underworld exists, the history of tattooing in Japan is far richer and older. Interestingly, tattoos were once used as punishment during the Edo period. Criminals might be marked with symbols, even the Tokugawa family symbol, as a form of legal reprieve from the death penalty. However, this punitive use stands in stark contrast to the elaborate and deeply meaningful Irezumi practiced by the Yakuza and others.

Yakuza tattoos are not about flaunting criminality or engaging in “plastic intimidation.” Instead, they are often elaborate narratives drawn from Japanese mythology, folklore, and classical literature. These scenes are chosen to reflect personal values, aspirations, and a sense of inner strength. Symbols of punishment are considered undesirable, reflecting a nuanced understanding of honor and shame within Yakuza culture.

Close-up of Horiyoshi III meticulously wrapping the ribs of a Yakuza client during a full body suit tattoo session.

Close-up of Horiyoshi III meticulously wrapping the ribs of a Yakuza client during a full body suit tattoo session.

Hidden Meanings: Strength and the Shadow Aesthetic

The very nature of Yakuza tattoos – often full body suits meticulously crafted to be hidden beneath clothing – speaks volumes about their intended purpose. They are not designed for public display as a means of gang affiliation. If Yakuza members wished to openly declare their allegiance, visible tattoos would suffice. Instead, the hidden nature of Irezumi points to a different motivation.

Horiyoshi explains that the concept of “ninkyō,” meaning helping those less fortunate, is traditionally associated with the Yakuza. Yakuza tattoos, in this context, become a personal testament to inner strength – a strength intended to be used to protect and assist the weak. This strength doesn’t require public validation; its power lies in its hidden existence.

Inside Horiyoshi III's studio, displaying traditional Japanese decorations and gifts, reflecting the cultural context of Yakuza tattoos.

Inside Horiyoshi III's studio, displaying traditional Japanese decorations and gifts, reflecting the cultural context of Yakuza tattoos.

This philosophy of hidden beauty is deeply ingrained in Japanese aesthetics. Horiyoshi draws a parallel to fireflies, whose beauty is only revealed in the darkness of night. Similarly, hidden tattoos hold a unique fascination precisely because they are not constantly on display. Japanese culture, unlike some aspects of Western culture, finds beauty in the shadows, in the subtle and the unseen. Temples are dimly lit, contrasting with the bright opulence of Western churches. This appreciation for shadows is central to understanding the Yakuza tattoo ethos.

The Art of Subtlety and the Japanese Shadow

The Japanese approach to aesthetics emphasizes using shadows to define light. Instead of starting with light and understanding shadows, Japanese art and culture often begin with the shadow to illuminate the light. This is reflected in various art forms, from Noh theatre performed in firelight, where costumes shimmer in the darkness, to architecture that carefully considers the interplay of sunlight and shadow.

A detailed back piece tattoo on a young Yakuza member, exemplifying the artistry and scale of traditional Irezumi.

A detailed back piece tattoo on a young Yakuza member, exemplifying the artistry and scale of traditional Irezumi.

Even the famed Sankeien gardens are designed to manipulate light and shadow throughout the year, creating a living, breathing artwork. This sensibility extends to tattoos. Yakuza members, and those who embrace Irezumi, understand that the true power and beauty of these tattoos emerge from their hidden nature. They are not fleeting trends but profound personal statements, appreciated on a deeper, more intimate level.

Craftsmanship vs. Art: Horiyoshi’s Perspective

Despite the undeniable artistry of Irezumi, Horiyoshi himself identifies as a craftsman, not an artist. He draws a comparison to traditional Japanese sculpture, suggesting that the creators may have seen themselves as skilled artisans rather than “artists” in the modern Western sense. This humility and focus on craft are central to the Japanese approach to many disciplines.

An elder Yakuza member displaying a vibrant Koi fish tattoo, a symbol of strength and perseverance in Japanese tattoo art.

An elder Yakuza member displaying a vibrant Koi fish tattoo, a symbol of strength and perseverance in Japanese tattoo art.

Horiyoshi’s perspective challenges conventional Western notions of art. He points to the concept of negative space in traditional Japanese scroll paintings, where the absence of paint is considered the ultimate art form, inviting the viewer’s imagination. He questions the very definition of art in a modern world where context and perception heavily influence value.

Conclusion: The Enduring Fascination of Yakuza Tattoos

Yakuza tattoos are far more than just body decorations associated with organized crime. They are a complex tapestry woven from Japanese history, mythology, aesthetics, and a unique cultural perspective on beauty and strength. Their hidden nature, their intricate symbolism, and the dedication of both artist and wearer contribute to their enduring fascination. Irezumi, particularly in the context of Yakuza culture, offers a powerful counterpoint to the often-exhibitionist nature of Western tattoo trends, reminding us that true depth and meaning can often be found in the shadows.