Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy introduced the world to Lisbeth Salander, a character as captivating as she is complex. This goth- Hacker with a profound aversion to social norms and an extraordinary intellect quickly became a cultural icon. Her traumatic past, marked by witnessing her father’s violence against her mother and the subsequent retaliatory act that led to her being declared legally incompetent, shapes her intense hostility towards abusive men. When we first meet her in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, she’s employed by a security firm and has just completed a thorough background check on a prominent magazine publisher, setting the stage for a thrilling and intricate narrative.

The allure of Lisbeth Salander isn’t confined to the pages of Larsson’s novels. Her character has been brought to life on screen multiple times, leading to fascinating interpretations. We are presented with not just one, but three distinct versions of this compelling woman: the literary Lisbeth from Larsson’s book, Noomi Rapace’s fierce portrayal in the original Swedish film, and Rooney Mara’s critically acclaimed performance in David Fincher’s American remake, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movie. While all three capture the essence of Salander, subtle yet significant nuances differentiate them. Compounding these character variations are the narrative shifts between the novel and its film adaptations, creating a rich tapestry of interpretations that can be both intriguing and, at times, bewildering.

Let’s begin by revisiting the source material, the novel The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo. As a gripping “locked room” mystery, it pairs the tenacious journalist Mikael Blomkvist with the enigmatic Lisbeth Salander. This unlikely duo embarks on a quest to unravel the decades-old disappearance of a young woman, inadvertently uncovering a dark history of serial murder and sexual abuse.

While the novel garnered significant hype and commercial success, it remains firmly rooted in the genre fiction category. Larsson crafts a procedural narrative that, despite its length, is remarkably readable. The pages turn effortlessly, drawing readers into the intricate investigation. However, the novel isn’t without its flaws. Some plot points, particularly the final revelation, require a degree of suspension of disbelief, and the religious undertones occasionally feel somewhat forced. Yet, the compelling characters, especially Lisbeth Salander, leave a lasting impression, making the prospect of sequels worthwhile, even if the immediate plot feels somewhat resolved.

One notable aspect of the novel is its extensive exposition, particularly in the initial chapters. Detailed explanations of Swedish financial laws and political history, while perhaps adding depth to the setting, often impede the narrative flow and can deter some readers. Thankfully, neither the Swedish nor the American film adaptations attempt to replicate this level of detail, streamlining the story for the screen. Despite these minor criticisms, the book’s page-turning quality is undeniable, even if the prose occasionally leans towards the functional rather than the lyrical.

Despite any reservations about the novel’s literary style, the prospect of seeing Lisbeth Salander’s story adapted for film was undeniably exciting. History is replete with examples of novels that, while imperfect on the page, become cinematic masterpieces (The Godfather being a prime example). The Swedish film adaptation was viewed shortly after finishing Larsson’s novel, and the initial reaction was somewhat underwhelming. While Noomi Rapace delivered a powerful performance as Lisbeth, the film felt sluggish in pacing. The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, at its core, is a story about investigative journalism and meticulous research. The Swedish film, while faithful to the plot, struggled to translate this inherently cerebral process into truly captivating cinema.

Therefore, the announcement of David Fincher directing an English-language remake of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movie sparked considerable excitement. Fincher, known for his meticulous direction and ability to create tension, seemed like the ideal choice to inject dynamism into the narrative. His previous work, particularly the criminally underrated Zodiac, demonstrated his mastery in making the minutiae of investigation riveting. Zodiac, a film largely consisting of characters poring over documents and following leads, is a testament to Fincher’s ability to make the seemingly mundane utterly engrossing.

Adding to the anticipation was the promise of a revised ending for the American remake. Reports suggested that screenwriter Steven Zaillian had significantly altered the conclusion, diverging from the novel’s climax. This deviation from the source material was touted as an improvement, with the new ending promised to be more compelling and dramatically satisfying. The combination of Fincher’s directorial talent and a potentially enhanced narrative resolution created high expectations for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movie. Coming hot off the heels of The Social Network, Fincher’s directorial stock was at an all-time high, further fueling anticipation.

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in the Swedish film adaptation of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in the Swedish film adaptation of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

Attending the opening night of Fincher’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movie was an event filled with anticipation. The film’s opening sequence, a visually striking monochrome nightmare set to the pulsating rhythm of Karen O’s music, immediately set a dark and intense tone. This opening music video segment seamlessly transitions into the familiar world of snow-covered Sweden, piercings, leather, and the enigmatic Lisbeth Salander. Fincher’s technical prowess revitalizes the familiar elements of the story, and Rooney Mara’s portrayal of Lisbeth is nothing short of revelatory. She embodies damaged goods with such intensity that the audience is immediately drawn to her, yearning to understand her and earn her trust in a way that mirrors Blomkvist’s journey. The atmospheric score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross further enhances the mood, creating a hypnotic backdrop to the unfolding drama. The film’s runtime of nearly three hours seems to vanish in an instant, a testament to its captivating nature.

Despite the film’s undeniable strengths, a sense of dissatisfaction lingered after leaving the theater. Perhaps expectations had been set too high, but it felt as though Fincher’s adaptation hadn’t fully rectified the inherent weaknesses of the source material. Post-viewing discussions with friends attempted to pinpoint the exact reasons for this feeling of incompleteness.

One immediate realization was that the promise of a “completely changed ending” had been somewhat misleading. The anticipation of a radically different climax had been built up, but the actual differences proved to be less substantial than anticipated. To clarify these discrepancies, a return to the source material and a re-examination of the Swedish film became necessary. After revisiting both, and watching Fincher’s remake a second time, the nuances and differences began to solidify.

The Swedish film, directed by Niels Arden Oplev, emerged as a more accomplished adaptation than initially perceived. It contained crucial details that were surprisingly absent from Fincher’s version. One such detail is the foreshadowing of Lisbeth’s attempted patricide. While it’s debatable whether this event is explicitly revealed in the first novel, Oplev’s film incorporates brief flashbacks, culminating in a full reveal of this pivotal moment in Lisbeth’s past. In contrast, Fincher’s film relegates this crucial backstory element to a brief, almost throwaway line during a late-night conversation between Lisbeth and Blomkvist, lacking the necessary context and emotional weight.

Furthermore, the Swedish film offers a more nuanced portrayal of Blomkvist’s romantic life. While not as overtly promiscuous as his literary counterpart, he is depicted as more romantically engaged than Daniel Craig’s more reserved portrayal. The novel provides extensive backstory on Mikael’s relationship with Erika Berger, his colleague and co-owner of Millennium magazine. This established history makes their continued romantic entanglement understandable, though it understandably provokes Lisbeth’s jealousy. Fincher’s film, however, downplays the depth of Mikael and Erika’s relationship, leading the audience to believe in a potential romantic future between Blomkvist and Salander. When Mikael’s pre-existing relationship with Erika re-emerges, it feels more like a sudden betrayal, lacking the foreshadowing present in the novel and Swedish film. Interestingly, the Swedish film omits Lisbeth’s jealousy, instead portraying her withdrawal as a result of fear and self-preservation, a different interpretation of her character’s emotional response.

Another significant divergence lies in the method by which Blomkvist obtains the crucial evidence against Wennerstrom. In all three versions, Lisbeth ultimately provides this information. However, both the novel and Fincher’s film include a detail absent in the Swedish adaptation: Henrik Vanger’s initial promise to Blomkvist. In these versions, Blomkvist agrees to investigate the Vanger case only after Henrik promises to provide him with evidence to incriminate Wennerstrom. However, upon receiving the evidence, it proves unusable due to the statute of limitations. It is at this point that Lisbeth’s hacking skills become essential. Oplev’s film omits Henrik’s promise entirely.

While seemingly a minor alteration, this omission weakens Blomkvist’s initial motivation for taking on the Vanger case in the Swedish film. It diminishes his agency, making him appear less driven and more like someone seeking refuge from his personal problems rather than actively pursuing a professional goal. A strong protagonist is typically propelled by clear objectives, and this change makes Blomkvist appear somewhat passive in comparison.

The nuanced detail of Blomkvist’s childhood connection to Harriet and Anita Vanger is also more pronounced in the Swedish film and novel. This element adds another layer to Blomkvist’s motivation and investment in solving the mystery. The Swedish film emphasizes the physical resemblance between the cousins, a subtle foreshadowing element that enhances the narrative. This detail, regrettably absent in the American remake, could have enriched the film and made the eventual twist more organically integrated into the narrative.

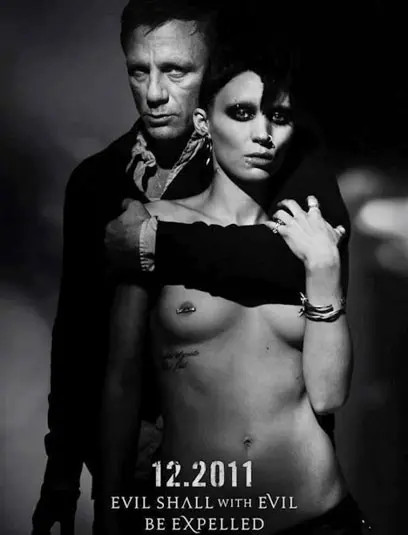

Rooney Mara as Lisbeth Salander in the American movie poster for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

Rooney Mara as Lisbeth Salander in the American movie poster for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

The endings of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movie adaptations also present notable variations. The discovery of Martin Vanger as the killer differs slightly across all three versions. In the novel, Blomkvist identifies Martin through a photograph where Martin wears the same jacket as the mysterious figure in a blurry parade photo. The Swedish film takes a different approach, with Blomkvist and Lisbeth deducing that the murder victims were Jewish, leading them to suspect Harald Vanger, a former Nazi. Blomkvist’s subsequent investigation at Harald’s home leads him to Martin, who ultimately reveals his true nature. Fincher’s film mirrors the Swedish version in the initial deduction about the victims’ religious background and the suspicion of Harald. However, Blomkvist’s discovery of Martin’s jacket photograph occurs during a seemingly innocuous conversation with Harald, after which he proceeds to Martin’s house, ultimately leading to his capture. In this instance, the Swedish film’s pacing and sequence of events feel slightly more organically constructed.

The manner of Martin Vanger’s demise also differs across adaptations. In Larsson’s novel, Martin deliberately drives his car into oncoming traffic, resulting in a fatal collision. The Swedish film portrays Martin losing control of his vehicle and crashing off the road. Lisbeth, arriving at the scene, chooses to let him perish in the ensuing fire. Fincher’s version also involves Martin losing control and crashing, but before Lisbeth can intervene, leaking gasoline ignites, engulfing the car in flames, removing the element of Lisbeth’s conscious choice.

The Swedish film’s ending stands out as the most morally complex. In the novel, Lisbeth’s declaration to Blomkvist, “I’m going to take him,” as she pursues Martin, implies an intention to kill him, but she is never actually tested. Her capacity for murder remains ambiguous. Fincher’s film makes Lisbeth’s intentions clearer when she asks Blomkvist, “May I kill him?” before pursuing Martin. However, the explosion prevents her from making a definitive choice. In contrast, the Swedish film presents Lisbeth with a stark moral dilemma. She witnesses Martin pleading for help, and in a moment of profound ambiguity, influenced by memories of her abusive father, she chooses inaction, becoming complicit in his death through her deliberate lack of intervention. This choice imbues her character with a deeper layer of moral complexity.

Finally, the “twist” regarding Harriet Vanger’s fate also varies. In both the novel and the Swedish film, Harriet is alive and living in Australia. In the novel, Blomkvist uncovers this by tapping Anita Vanger’s phone. The Swedish film attributes this discovery to Lisbeth’s hacking prowess. Fincher’s film initially follows the phone-tapping approach, but when Anita fails to call Harriet, Blomkvist deduces that Anita and Harriet are the same person. This conclusion feels somewhat abrupt and less organically developed. The revelation that Anita helped Harriet escape and subsequently assumed her identity after Anita’s death feels somewhat contrived in Fincher’s version. If the film had established Blomkvist’s earlier confusion between the cousins, as in the Swedish film, this twist might have landed with greater impact and plausibility.

However, neither ending is inherently superior. This particular change feels more cosmetic, failing to fundamentally address the somewhat cumbersome religious-turned-secular serial killer plotline. The religious aspect, even in the novel, felt somewhat tacked on. By the time of the Swedish film adaptation, it had become an accepted part of the narrative. However, for viewers unfamiliar with the source material or previous adaptations, Fincher’s film may lack sufficient detail explaining the shift from religious to secular killings. While the father-son dynamic is established, Martin’s explicit explanation of their differing modi operandi is less pronounced. Understanding the perspectives of those who have only seen Fincher’s film in relation to this aspect would be insightful.

Ultimately, no single adaptation of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movie emerges as definitively superior. Each version possesses its own strengths and weaknesses. The ideal rendition likely exists as a hypothetical Frankensteinian creation, piecing together the best elements from each. However, even with the perfect assembly of parts, the question remains whether the core story itself is truly exceptional. Dragon Tattoo boasts compelling characters, a captivating setting, and moments of suspense, but the underlying narrative is, at its heart, a fairly generic serial killer plot. Regardless of stylistic embellishments, the fundamental structure remains somewhat conventional. Furthermore, the novel’s sprawling nature and intricate details don’t always translate seamlessly to film. The “locked room” mystery aspect is somewhat diluted in both adaptations, lacking a sufficient array of red herrings to truly engage the audience in active deduction. The films tend to guide viewers directly to the conclusion, leaving less room for independent speculation or surprise.

If forced to choose a definitive version, a non-committal compromise would be to advocate for a script based on the Swedish film (with minor adjustments), directed by David Fincher, and starring Rooney Mara. This hypothetical “perfect” adaptation would also selectively incorporate certain impactful scenes from Oplev’s film. Despite the marketing emphasis on Fincher’s remake as the darker and grittier version, the Swedish film often surpasses it in visceral impact. The subway attack scene in the Swedish film, for instance, feels rawer and more brutal. Lisbeth’s laptop is not merely broken by a thief; it’s destroyed during a violent assault by a group of men. The scene culminates in a feral Lisbeth, foaming at the mouth and brandishing a broken bottle, a far cry from the more stylized violence in the American remake. Even Lisbeth’s initial mistreatment by Bjurman is arguably more intensely portrayed in Oplev’s film. And regarding the subsequent, more graphic assault, debating which rape scene is “more hard-hitting” feels inappropriate; suffice it to say both are profoundly disturbing.

Lisbeth Salander remains a complex and enigmatic figure. No single interpretation, be it literary or cinematic, fully encapsulates her multifaceted nature. She defies easy categorization, resisting attempts to be tamed or fully understood. Perhaps it is this very unruliness, these imperfections and contradictions, that make her so compelling. The narrative arc continues in The Girl Who Played With Fire, arguably the strongest novel in Larsson’s trilogy and a standout installment in the Swedish film series. Moving beyond the serial killer tropes of Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played With Fire delves deeper into Lisbeth’s backstory and presents a more intricate and compelling conspiracy plot that carries through to the trilogy’s conclusion. The hope remains that Fincher might revisit this world and bring his directorial vision to the subsequent chapters of Lisbeth Salander’s story.