The Ss Blood Group Tattoo remains a chilling symbol of Nazi Germany’s Waffen-SS, a paramilitary organization infamous for its role in World War II atrocities. This seemingly innocuous tattoo, typically placed on the underside of the left arm, served a practical purpose rooted in battlefield necessity but became deeply entwined with the SS’s brutal legacy and post-war attempts at concealment.

The primary function of the SS blood group tattoo was to provide immediate medical information in critical situations. In the chaos of combat, a soldier might be rendered unconscious or separated from his Erkennungsmarke (dog tag) or Soldbuch (pay book), the standard identification methods of the Wehrmacht. In such instances, knowing a soldier’s blood type was crucial for administering life-saving blood transfusions. The tattoo ensured that medical personnel, known as Sanitäter, could quickly identify a soldier’s blood group, minimizing delays in treatment and potentially saving lives on the front lines. Typically, these tattoos were applied during basic training by unit medics, but could be administered by designated personnel at any point during a soldier’s service.

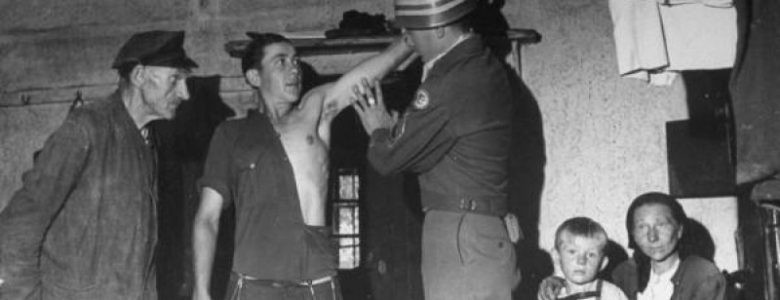

American soldiers search for SS soldiers in Germany, 1946

American soldiers search for SS soldiers in Germany, 1946

While officially mandated for all members of the Waffen-SS, the reality of SS blood group tattoos was more nuanced. Although a requirement, not every member received one. Notably, high-ranking officers and individuals who joined the Waffen-SS later in the war sometimes lacked the tattoo. The practice was most consistently applied to those undergoing basic training within the Waffen-SS. However, the reach of the tattoo extended beyond Waffen-SS personnel. Soldiers from other branches of the Wehrmacht who received treatment in Waffen-SS field hospitals could also be tattooed, highlighting the tattoo’s primary function as a medical identifier within the SS operational sphere.

Close-up of a purported SS blood group tattoo on a mannequin arm

Close-up of a purported SS blood group tattoo on a mannequin arm

The practical necessity of the SS blood group tattoo is undeniable in the context of wartime medical emergencies. Having blood type information readily available, not just in personnel files and ID papers, but directly on the soldier’s body, offered a significant advantage in critical care situations. This system was designed to improve the efficiency of blood transfusions in the field, a crucial aspect of battlefield medicine during WWII.

American soldiers searching for SS members post-WWII

American soldiers searching for SS members post-WWII

Variations existed in the SS blood group tattoos. Early tattoos utilized Gothic lettering, while later in the war, Latin lettering became more common. Regardless of script, the tattoo’s size remained small, approximately 7mm in length, and its placement was standardized on the underside of the left arm, roughly 20 cm above the elbow. This consistency in size and location further facilitated quick identification by medical personnel.

However, the SS blood group tattoo’s significance transcended its medical purpose, particularly in the aftermath of WWII. The tattoo became a key tool for Allied forces in identifying former members of the SS. The Waffen-SS, due to the extensive war crimes committed by certain units, was declared a criminal organization by the Nuremberg trials. Consequently, identifying and prosecuting former SS members became a priority for the Allies.

Example of an SS blood group tattoo

Example of an SS blood group tattoo

The tattoo, intended for medical expediency, now served as an indelible mark of SS affiliation. Many former SS soldiers and Waffen-SS veterans recognized the incriminating nature of the tattoo and sought to remove it to conceal their past from Allied authorities. Methods of removal ranged from crude home remedies to surgical procedures, reflecting the desperation to erase this visible link to the disgraced organization.

One account from a soldier of the 13th Waffen-Gebirgs-Division der SS Handschar illustrates the efforts to remove these tattoos. In a prisoner-of-war camp, he and others received hydrogen tablets from a physician of the 14th SS Division. These tablets, when moistened and applied, chemically burned away the tattoo over a few days, albeit with significant skin irritation and a prolonged healing process. This drastic measure allowed some to pass Allied inspections and avoid detection.

Despite the efforts to remove them, SS blood group tattoos played a significant role in post-war identification. The Allies actively sought out individuals bearing these tattoos, understanding their strong correlation with SS membership. While not foolproof – some SS members never received tattoos, and some non-SS individuals might have – the tattoo served as a valuable indicator, contributing to the prosecution and, in some instances, execution of former SS personnel.

The imperfect correlation between the tattoo and SS membership allowed some prominent figures to evade immediate capture, partly due to the absence of this incriminating mark. Notorious figures like Josef Mengele, the “Angel of Death,” and Alois Brunner, key figures in the Holocaust, were among those who escaped detection, in part because they lacked the blood group tattoo.

In the war’s closing stages and its aftermath, the desperation to shed the SS affiliation intensified. Beyond chemical burns, former SS members resorted to surgery, self-inflicted burns, and even gunshot wounds to the tattooed area in attempts to obliterate the mark. The U.S. Army, recognizing this pattern, even published materials to help identify self-inflicted wounds in the tattoo’s location, demonstrating the lengths to which individuals went to erase this symbol of their past and the Allies’ determination to uncover it.

In conclusion, the SS blood group tattoo, initially intended as a practical tool for battlefield medicine, evolved into a potent symbol of SS membership and a focal point of post-war accountability. Its dual nature – as a medical aid and an identifier of affiliation with a criminal organization – underscores the complex and dark history of the Waffen-SS and the enduring legacy of symbols in times of conflict and reckoning.