Polynesian tattoo art is more than just skin deep; it’s a rich tapestry of history, culture, and symbolism. For centuries, these intricate designs have served as powerful forms of expression, identity, and storytelling within Polynesian societies. Understanding the depth and meaning behind Polynesian Tattoo Symbols is crucial for appreciating this ancient art form and respecting its cultural origins.

The Deep Roots of Polynesian Tattooing

The origins of Polynesian society and tattooing are intertwined in a history that spans millennia. While debates continue about the precise beginnings, it’s clear that Polynesian culture, including its tattooing traditions, has roots in Southeast Asia. The term “Polynesia” encompasses a vast array of island nations and cultures, including Marquesans, Samoans, Niueans, Tongans, Cook Islanders, Hawaiians, Tahitians, and Maori, all linked by shared ancestry, language, and cultural threads.

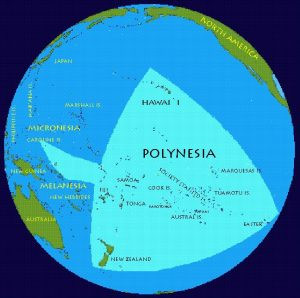

This expansive region, often visualized as the Polynesian Triangle with New Zealand, Hawaii, and Easter Island at its corners, is home to people who share fundamental concepts and beliefs. Words like “moana” (ocean) and “mana” (spiritual power) resonate across Polynesian languages, highlighting the profound connection to the sea and the spiritual world that shapes their culture.

Polynesian Triangle encompassing New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter Island

Polynesian Triangle encompassing New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter Island

Historically, lacking a written language, Polynesians relied on tattoo art as a visual language. These tattoos were far more than mere decoration; they were integral to expressing identity, social status, genealogy, and personal narratives. In ancient Polynesian society, tattooing was almost universal, marking significant life stages and societal roles.

European contact in the late 16th century, beginning with Spanish explorers in the Marquesas Islands in 1595, initially showed little interest in Polynesian culture. It was Captain James Cook’s voyages in the 18th century that brought Polynesia and its tattooing traditions to European attention.

In 1771, Cook’s return from his first voyage to Tahiti and New Zealand introduced the word “tattoo” to the Western world, derived from the Tahitian word “tatau.” The Tahitian man Ma’i, who Cook brought to Europe, further popularized tattoos, captivating Europeans with his inked skin. Sailors, fascinated by Polynesian tattoos, adopted the practice, contributing to its rapid spread in Europe.

However, the ancient tradition of Polynesian tattooing, dating back over 2000 years, faced challenges. The rise of Christianity in the 18th century led to suppression of tattooing in some areas. Later, in the 20th century, health concerns regarding sterilization of traditional tools led to bans in some regions, such as French Polynesia in 1986. Despite these setbacks, a resurgence of Polynesian tattoo art began in the 1980s, driven by scholars, artists, and a renewed appreciation for cultural heritage.

Tonga and Samoa: Centers of Refined Tattoo Art

Tonga and Samoa emerged as pivotal centers in the development of Polynesian tattoo art. In these cultures, tattooing evolved into a highly sophisticated art form with deep cultural significance. Tongan warriors were extensively tattooed from waist to knees with geometric patterns, primarily triangles, bands, and solid black areas.

Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson showcasing his traditional Polynesian tattoo

Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson showcasing his traditional Polynesian tattoo

The tattooing process in Tonga was a sacred undertaking, performed by trained priests adhering to strict rituals and taboos. For Tongans, tattoos were profound markers of social and cultural identity.

Samoa also held tattooing in high esteem, embedding it in religious rituals and warfare. Samoan tattoo artists held hereditary and highly privileged positions. They traditionally tattooed groups of men in ceremonial settings, witnessed by family and friends. The Samoan warrior’s tattoo, known as the pe’a, covered the body from the waist to below the knees. While less common, Samoan women were also tattooed, often with delicate, geometric flower-like patterns on hands and lower bodies.

Around 200 AD, Samoan and Tongan voyagers settled in the Marquesas Islands, leading to the development of the complex Marquesan culture over centuries.

Marquesan Art: Elaborate Full-Body Designs

Marquesan culture became renowned for its highly developed art and architecture. Marquesan tattoo designs were particularly elaborate, often covering the entire body, representing the most complex tattooing traditions in Polynesia.

Traditional Tools and Techniques

Traditional Polynesian tattooing tools made of wood and bone

Traditional Polynesian tattooing tools made of wood and bone

Remarkably, the tools and techniques of Polynesian tattooing have remained largely unchanged over centuries. Traditional tattoo artistry was a skill passed down through generations. Tattoo artists, known as “tufuga” in Samoa, underwent years of apprenticeship to master their craft.

While tattooing was lost in Tonga with the arrival of Christianity, Samoa preserved its unbroken tradition of hand-tapped tattooing for over 2000 years. The “au,” a tattooing comb made of sharpened boar’s teeth bound to a turtle shell and wooden handle, remains the primary tool. Apprentices would practice for years, tapping designs into sand or bark cloth before working on skin.

The Ordeal of Pain and Healing

Polynesian tattooing was an intensely painful and lengthy process, a testament to endurance and commitment to cultural traditions. The risk of infection was significant, yet shying away from tattooing was considered an act of cowardice, leading to social ostracization.

The traditional Samoan pe’a, for example, was a full-body tattoo that men were expected to undergo. Using a mallet to tap the ink-laden comb into the skin, artists followed simple guidelines, relying on skill and tradition. Sessions lasted until dusk or until the recipient could no longer bear the pain, resuming over days or even months, allowing for healing breaks. The entire process could take up to four months. Upon completion, the community celebrated the individual’s endurance with a feast and ceremony.

The healing process was also extensive, lasting months. Washing with saltwater, massage, and assistance from family were crucial to prevent infection and promote healing. Even basic movements could be painful during this time. The full designs would become visible within six months, but complete healing took nearly a year.

Body Placement and Symbolism

The placement of tattoo elements on the body is deeply significant in Polynesian tattooing, influencing the overall meaning. Polynesian cosmology views humans as descendants of Rangi (Heaven) and Papa (Earth), once united. The body is seen as a bridge between these realms, with the upper body connected to the spiritual world and the heavens, and the lower body to the earthly realm.

Placement can also reflect time, with the back associated with the past and the front with the future. Gender symbolism also plays a role, with the left side often linked to women and the right to men.

Here’s a breakdown of body placement and associated meanings:

-

Head: The head, being the highest point, is the connection to Rangi, symbolizing spirituality, knowledge, wisdom, and intuition.

-

Higher Trunk (Chest to Navel): This area represents generosity, sincerity, honor, and reconciliation, acting as a point of harmony between Rangi and Papa.

-

Lower Trunk (Navel to Thighs): Linked to life energy, courage, procreation, independence, and sexuality. Thighs symbolize strength and marriage, the stomach is the origin of mana, and the navel represents independence.

-

Upper Arms and Shoulders: Associated with strength and bravery, representing warriors and chiefs. The Maori term “kikopuku” emphasizes the strength of this area.

-

Lower Arms and Hands: Symbolize creativity, creation, and making, reflecting the hands’ role in shaping the world.

-

Legs and Feet: Represent movement forward, transformation, and progress. They also relate to separation and choice. Feet, in contact with Papa (Earth), symbolize concreteness and material matters.

-

Joints: Often represent union and contact, reflecting social connections. Joints further from the head can symbolize greater distance in kinship or lower social status. Ankles and wrists symbolize ties and commitment, while knees relate to chiefs and kneeling in respect.

Important Note: While traditional placement holds significance, personal meaning is paramount. Choosing a placement that resonates with the individual’s story and intentions is always encouraged.

Deciphering Polynesian Tattoo Symbols and Motifs

Polynesian tattoo art utilizes a rich visual vocabulary of symbols, each carrying specific meanings and contributing to the overall narrative of the tattoo. Here are some key symbols and their interpretations:

-

Enata (Singular): Representing human figures, “enata” in Marquesan can depict men, women, or gods. They symbolize people and relationships. Upside-down enata can represent defeated enemies.

-

Enata (Pattern): Stylized enata linked in a row, forming the “ani ata” motif, meaning “cloudy sky.” Rows of enata can also symbolize ancestors watching over descendants.

-

Shark Teeth (Simplified): “Niho mano” or shark teeth are significant symbols, as sharks are revered as “aumakua” (spiritual guardians) in Polynesian cultures. They represent protection, guidance, strength, ferocity, and adaptability.

-

Shark Teeth (Complex): More stylized variations of shark teeth are also common in tattoos, retaining the core symbolism of protection and strength.

-

Spearhead: A classic symbol of the warrior spirit, spearheads represent courage and the warrior ethos. They can also symbolize sharpness and the sting of certain animals.

-

Spearhead (Pattern): Rows of spearheads are a common motif, emphasizing the themes of strength and warfare.

-

Ocean (Simplified): The ocean is central to Polynesian life and mythology, representing life, sustenance, and the journey to the afterlife. Simplified wave patterns symbolize the ocean, life, and continuity.

-

Ocean (Stylized): Stylized waves can represent life, change, continuity through change, and the spiritual realm or afterlife.

-

Tiki: “Tiki” refers to human-like figures representing semi-gods, deified ancestors, priests, or chiefs. They symbolize protection, fertility, and guardianship.

Tiki symbol representing semi-gods and protection

Tiki symbol representing semi-gods and protection

-

Tiki Eyes: Emphasizing the eyes of the tiki, this symbol focuses on vigilance, protection, and spiritual awareness.

-

Turtle: The turtle or “honu” is revered across Polynesia, symbolizing health, fertility, longevity, foundation, peace, and rest. The Marquesan word “hono” also relates to joining and unity, representing family connection.

Turtle symbol representing health, longevity and family unity

Turtle symbol representing health, longevity and family unity

-

Turtle Shell Pattern: Patterns derived from turtle shells are also used in designs, often embodying similar meanings of protection and longevity.

-

Lizard: Lizards and geckos, known as “mo’o” or “moko,” are significant in Polynesian myth, often seen as earthly manifestations of gods (“atua”). They symbolize good luck, communication between worlds, and access to the invisible realm. However, they can also represent bad omens if disrespected.

Lizard symbol representing good luck and communication with gods

Lizard symbol representing good luck and communication with gods

-

Lizard (Pattern): Stylized lizard patterns, similar in form to enata patterns, are also used in tattoos, embodying the lizard’s symbolic meanings.

-

Stingray: Stingrays symbolize protection, adaptation, grace, peacefulness, agility, speed, and stealth, reflecting their ability to hide and defend themselves.

Stingray symbol representing protection and adaptability

Stingray symbol representing protection and adaptability

Your Polynesian Tattoo Journey

Understanding Polynesian tattoo symbols opens a door to appreciating the depth and artistry of this ancient tradition. When considering a Polynesian tattoo, researching the meanings of symbols and working with an artist knowledgeable in Polynesian art ensures a respectful and meaningful piece that reflects your personal story within this rich cultural context.

To explore more Polynesian tattoo designs, visit our Polynesian Tattoo Gallery or contact us to discuss your ideas and begin your tattoo journey.

Polynesian arm tattoo design

Polynesian arm tattoo design