Lisbeth Salander, the enigmatic protagonist of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy, is a character etched in the minds of readers and viewers alike. A brilliant computer hacker with a severe aversion to social norms and a profound hostility towards abusive men, her complex persona is central to the series’ allure, particularly in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo. This novel, the first in the trilogy, introduces us to Lisbeth as she conducts a background check for a security firm, setting the stage for her intricate involvement in a decades-old mystery.

The challenge of portraying Lisbeth Salander extends beyond the pages of Larsson’s novels. We are presented with not one, but three distinct interpretations of this compelling character: the literary Lisbeth from the books, Noomi Rapace’s raw portrayal in the Swedish films, and Rooney Mara’s nuanced performance in David Fincher’s American adaptation. While each version captures the core essence of Lisbeth, subtle yet significant differences distinguish them, further complicated by the narrative deviations between the source material and its cinematic counterparts. Navigating these variations can be a perplexing, yet fascinating, endeavor for any fan of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo.

Having revisited the source material and both film adaptations, let’s delve into a comparative analysis, starting with a reminder of the book’s premise. As previously summarized:

The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo [is] a large scale “locked room” mystery that introduces us to dashing journo, Mikael Blomkvist, and socially awkward heroine, Lisbeth Salander. The unlikely pair join forces to investigate the decades old mystery of a missing girl, uncovering a heinous history of serial murder and sexual abuse in the process.

The initial reaction to the novel was one of acknowledging its genre roots while appreciating its readability:

For all the hype, Dragon Tattoo is still a mass market genre novel. A well written one, but a genre novel all the same. Being a genre novel, it is not completely devoid of the associated cliches. The story itself is highly procedural, but to Larsson’s credit, it is also immensely readable. For a book its size, the five-hundred plus pages practically turn themselves. The final revelation is a bit of a stretch, and I found the religious angle superfluous at times, but it works well enough given the material. The book doesn’t warrant a sequel based on plot, but there are enough unanswered questions regarding the characters, especially Salander, to make the endeavor worthwhile.

One aspect often cited as a hurdle in the novel is its expository nature, particularly in the early sections. Detailed explanations of Swedish finance laws and political history, while perhaps adding depth to the setting, can feel tangential to the central narrative. Film adaptations wisely sidestep much of this, streamlining the story for a visual medium. Despite these digressions, the book’s gripping plot and the intrigue surrounding Lisbeth Salander, with her iconic Dragon Tattoo, propel the narrative forward, making it a compelling read.

The prospect of adapting Lisbeth’s intricate story for the screen was always intriguing. Often, novels with certain shortcomings can find new life and impact through film. The Swedish film adaptation was viewed shortly after finishing the book, and the initial impression was somewhat underwhelming. While Noomi Rapace’s portrayal of Lisbeth was a clear highlight, capturing the character’s fierce independence and vulnerability, the film itself felt somewhat slow-paced, struggling to translate the investigative nature of the book into engaging cinema. The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo at its heart is about meticulous research and piecing together clues, a process not inherently cinematic.

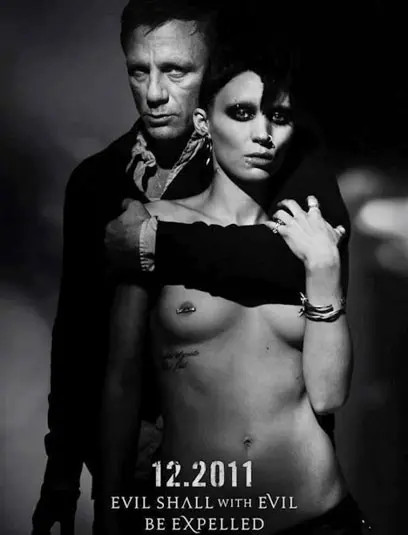

The announcement of David Fincher directing an English-language remake sparked considerable excitement. Fincher’s directorial prowess, demonstrated in films like Zodiac, known for making detailed procedural work captivating, seemed perfectly suited to bring The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo to life for a wider audience. Furthermore, the news of a revised ending raised hopes for a more impactful climax than the book offered. As reported by ‘W’ Magazine:

The script […] was written by Academy Award winner Steven Zaillian […] and it departs rather dramatically from the book. Blomkvist is less promiscuous, Salander is more aggressive, and, most notably, the ending—the resolution of the drama—has been completely changed. This may be sacrilege to some, but Zaillian has improved on Larsson—the script’s ending is more interesting.

This promised a fresh take, potentially refining the source material’s weaknesses. With Fincher at the helm, expectations were high for a compelling and improved cinematic experience of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo.

The opening night of Fincher’s film was met with anticipation. The film’s opening sequence, a visually striking and musically intense introduction, immediately set a distinct tone. Then, the film transitions into the familiar world of snow-covered Sweden, introducing Rooney Mara’s Lisbeth Salander. Mara’s portrayal is instantly captivating, embodying the damaged and fiercely independent nature of Lisbeth. The audience is drawn to her, eager to understand the complexities behind her hardened exterior, marked visually by her piercings and, of course, the dragon tattoo, a symbol of her rebellious spirit. The film masterfully creates an atmosphere of intrigue and unease, driven by the compelling central character and the atmospheric score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. The nearly three-hour runtime feels surprisingly swift, a testament to Fincher’s engaging direction.

Despite the film’s strengths, a sense of dissatisfaction lingered after the viewing. Perhaps inflated expectations played a role, but it felt as though Fincher’s adaptation hadn’t fully addressed all the shortcomings of the source material. Post-viewing discussions with friends sought to pinpoint the specific areas that felt lacking.

One immediate point of contention was the promise of a significantly altered ending. The anticipation of a completely new resolution had been a major draw. However, as the credits rolled, the actual changes felt less dramatic than advertised. To clarify these discrepancies, a comparative analysis was undertaken, revisiting the book, re-watching the Swedish film, and then seeing Fincher’s remake a second time. This detailed comparison aimed to dissect the nuances of each version and understand where each succeeded and faltered in adapting The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo.

Re-examining the Swedish film, directed by Niels Arden Oplev, revealed its merits more clearly. It contained details that were surprisingly absent in Fincher’s version, details that enriched the narrative and character depth. One such detail was the foreshadowing of Lisbeth’s attempted patricide. While it’s unclear if the novel explicitly reveals this in the first installment, Oplev’s film incorporates flashbacks, culminating in a full reveal of this traumatic event. Fincher’s film, in contrast, only briefly mentions this towards the end, almost as an afterthought, lacking the impactful backstory and context provided in the Swedish adaptation. This omission weakens the understanding of Lisbeth’s character and her motivations, especially concerning her violent tendencies and distrust of authority figures. The dragon tattoo itself, while visually present, becomes less symbolic of her past trauma and rebellion without this crucial backstory being fully explored.

Another notable difference lies in the portrayal of Mikael Blomkvist’s relationships. The Swedish film offers a more nuanced depiction of Blomkvist as a lover. While not as overtly promiscuous as in the book, he is also not as emotionally reserved as Daniel Craig’s portrayal in the Fincher film. The novel provides significant backstory regarding Mikael’s long-standing relationship with Millennium co-owner Erika Berger. This context makes their resumed intimacy, and Lisbeth’s subsequent reaction, more understandable. Fincher’s film, by minimizing this backstory, creates a somewhat misleading impression of a budding romance between Lisbeth and Mikael, making the later betrayal feel more abrupt and less justified within the narrative. Conversely, the Swedish film, while omitting Lisbeth’s jealousy, portrays her distancing herself from Blomkvist out of fear and vulnerability, a different but equally valid interpretation of her character.

A crucial plot point that varies between the book and the films is how Blomkvist ultimately secures the evidence against Wennerstrom. In all versions, Lisbeth is instrumental in providing this information. However, both the book and Fincher’s film include a detail absent in the Swedish adaptation: Henrik Vanger’s promise to Blomkvist to provide evidence against Wennerstrom in exchange for investigating Harriet’s disappearance. In the book and Fincher’s film, this evidence initially proves useless due to the statute of limitations, highlighting Lisbeth’s crucial role in uncovering the actionable information. The Swedish film omits Henrik’s promise entirely.

While seemingly minor, this omission in the Swedish film weakens Blomkvist’s initial motivation for taking on the Vanger case. It diminishes his agency and makes him appear less driven by his professional goals, instead suggesting he takes the job merely to escape his personal troubles. A strong protagonist is typically driven by clear objectives, and this nuance is somewhat lost in the Swedish adaptation. While it certainly elevates Lisbeth’s role and emphasizes her capabilities, it comes at the cost of weakening Blomkvist’s narrative arc.

Another subtle yet enriching detail present in the novel and expanded upon in the Swedish film is Blomkvist’s childhood connection to Harriet and Anita Vanger. This backstory adds another layer to Blomkvist’s personal investment in the case, making his determination to solve Harriet’s disappearance more emotionally resonant. The Swedish film even emphasizes the cousins’ resemblance, a visual cue that subtly foreshadows the altered ending in Fincher’s adaptation. Including this detail in the remake could have enhanced the impact of the “twist” ending, making it feel less arbitrary and more organically connected to the established narrative threads.

Moving to the endings, variations exist across all three versions regarding Blomkvist’s discovery of Martin as the killer. In the novel, it’s a picture of Martin wearing the same jacket as the mystery man in the parade photo. The Swedish film has Blomkvist and Lisbeth deducing the victims were Jewish, suspecting Harald Vanger, leading to a confrontation at Harald’s house where Martin intervenes. Fincher’s film similarly has them suspect Harald, but Blomkvist’s visit leads him to a photo of Martin in the jacket, prompting him to investigate Martin’s house. The Swedish film’s approach feels slightly more organically developed in this particular sequence.

The manner of Martin’s demise also differs. In the novel, Martin intentionally crashes his car. The Swedish film has Martin lose control, and Lisbeth chooses not to save him from the burning wreckage, a morally ambiguous choice. Fincher’s version also involves a car crash, but a gas leak ignites the vehicle before Lisbeth can intervene, removing her agency in Martin’s death.

The Swedish film’s ending is arguably the most morally complex. In the book and Fincher’s film, Lisbeth’s intention to “take” Martin is implied, but not explicitly tested. Fincher’s version even has her ask Blomkvist, “May I kill him?” but the explosion intervenes. The Swedish film, however, presents Lisbeth with a direct choice: to save Martin or let him perish. Her inaction, influenced by her traumatic past with her father, makes her complicit in his death, adding a layer of moral ambiguity to her character, aligning with the complex nature hinted at by her dragon tattoo – a symbol that can represent both power and vulnerability.

Finally, the “twist” ending concerning Harriet’s fate diverges significantly. The novel and Swedish film reveal Harriet is alive in Australia, discovered through phone tapping. Fincher’s film changes this dramatically: Anita Vanger is Harriet, having assumed her deceased cousin’s identity. This revelation feels somewhat abrupt in Fincher’s version, lacking the subtle foreshadowing that could have made it more impactful. Had Blomkvist’s confusion between the cousins been established earlier, as in the Swedish film, this twist might have resonated more effectively.

Despite these differences in endings, neither version fundamentally resolves the underlying issues with the religious-turned-generic serial killings plotline, which felt somewhat tacked-on even in the book. Fincher’s film, in particular, feels less detailed in explaining the shift in the killer’s MO, leaving those unfamiliar with the source material potentially confused about the motivations behind the murders.

In terms of pacing and resolution, novels and films have different demands. The epilogue in both the Swedish and American films feels somewhat extended, but Fincher’s version particularly so. The Swedish film concludes with a brief scene of Lisbeth’s ingenious financial maneuver against Wennerstrom. Fincher’s film, however, dedicates a more substantial portion to this subplot, which, while showcasing Lisbeth’s skills, feels somewhat protracted and detracts from the resolution of the central mystery. A tighter, more focused ending, as seen in the Swedish film’s conclusion, might have been more effective.

Ultimately, no single version of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo emerges as definitively superior. Each adaptation – the book, the Swedish film, and the American remake – possesses its own strengths and weaknesses. A hypothetical “perfect” version might Frankenstein elements from each, combining the best aspects of storytelling, direction, and performance. However, even with the ideal combination of parts, the fundamental challenge remains: The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, despite its compelling characters and atmospheric setting, is built upon a somewhat generic serial killer plot. The “locked room” mystery aspect, diluted by the sprawling narrative, doesn’t fully translate to film, lacking sufficient red herrings to truly engage the audience in deductive reasoning. The films primarily follow the investigation linearly, revealing the killer in a somewhat predetermined manner.

If forced to choose, a preference would lean towards a script based on the Swedish film (with minor adjustments), directed by David Fincher, and starring Rooney Mara. This hybrid approach would capitalize on Mara’s captivating portrayal of Lisbeth, Fincher’s directorial skill in creating atmosphere and tension, and the Swedish film’s more nuanced and morally complex interpretations of certain scenes. While Fincher’s remake was heavily marketed as the darker and grittier version, the Swedish film arguably surpasses it in visceral impact in moments like the subway attack and the initial portrayal of Bjurman’s abuse. The Swedish film presents a rawer, more unsettling depiction of violence and exploitation.

Lisbeth Salander remains a complex and fascinating character, defying easy categorization or taming. Whether in Larsson’s novels, Rapace’s portrayal, or Mara’s interpretation, she embodies a rebellious spirit, marked both internally and externally, most visibly by her dragon tattoo. This symbol, like Lisbeth herself, carries layers of meaning, representing strength, vulnerability, and a fierce independence. The enduring appeal of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo lies in this complexity, in the unresolved questions surrounding Lisbeth, and in the promise of further exploration in the subsequent installments of the Millennium Trilogy. The next chapter, The Girl Who Played With Fire, is eagerly anticipated, holding the potential for even greater depth and intrigue.