Stepping into the tattoo parlor in Los Angeles, a familiar wave of nervousness washed over me. It wasn’t my first foray into body art, but my last tattoo dated back to 2008 – a lifetime ago, marked by life changes and growth. Back then, children were not in the picture; my husband and I were navigating the uncertainties of trying to conceive. “Hope,” the word I chose to ink onto my forearm, served as a constant reminder during those challenging times. Years later, after navigating loss and longing, our family blossomed with two daughters.

The aroma of antiseptic and ink hung in the air, mingling with the rhythmic buzz of tattoo machines – a sound that instantly transported me back and hinted at the sharp sting to come. The walls were a vibrant tapestry of tattoo art – anchors, hearts pierced by swords, pin-up girls, roses, snakes, and an abundance of swords.

Approaching the counter, I rummaged for the printed directions and paperwork. The heavily tattooed artist chuckled at my printed map, a reaction that surprisingly put me at ease. I could see myself through his eyes: a somewhat reserved, 45-year-old mother in her cardigan.

This is a photograph of Carrie Friedman Lloyd with her father, capturing a tender moment between a daughter and her dad.

I presented my design – my dad’s last coherent words to me, spoken years before Parkinson’s and dementia stole his voice. I wanted his words in his own handwriting. For weeks, I meticulously traced and retraced his script from old letters and cards, striving to capture its essence perfectly.

At the parlor, after paying the fee, the artist transferred the design to my inner wrist. With my approval, the needle began its work. The pain, a vibrating bee sting, was more intense than I remembered. Sweat broke out, dizziness followed, and a wave of nausea washed over me. Nerves and anticipation were taking their toll.

To center myself, I closed my eyes, focusing on the profound meaning behind this Dad Tattoo.

It was March 2019, during a visit to my father in his nursing home. Parkinson’s and dementia had confined him to a wheelchair, stealing his physical steadiness and cognitive clarity.

“How’s your dad?” he asked me, his words slurred but recognizable.

Hesitantly, I began, “I don’t know,” then countered with, “How are you? You are my father.” He nodded urgently, as if we were playing a silent game of charades. For the first time during my visit, his eyes seemed to focus, truly seeing me.

“But how’s your dad?” he repeated softly, his gaze unwavering.

“I don’t know,” I admitted, feeling inadequate. “I think he’s having a tough time,” I added, lamely.

He nodded again, then looked directly into my eyes and said, with surprising clarity, “You go on.”

Initially, I misinterpreted his words, wondering if he was telling me to leave, perhaps suggesting I was being too talkative – though that was rarely the case. Then, the true meaning dawned on me, flooding my memory with decades of phone calls he’d made before every flight.

“Now listen to me,” he’d say from a crackling airport payphone, using his calling card. “If anything happens to your mother and me – if our plane goes down – you must go on. You would dishonor us by not continuing with your life.”

His message varied slightly for each of us. My sister recalled his constant refrain: “You honor us by getting along with your brother and sister after we’re gone. No fighting. Stick together, understand?”

To me, his message was always, “Living well and taking care of yourselves is how you honor us.” As an estate-planning attorney, he had witnessed firsthand how grief could derail lives, leading to alcoholism, depression, and despair.

We, his children, had grown accustomed to these pre-flight calls, often rolling our eyes. “God, Dad, you’re so morbid!” I’d sometimes retort. “We get it, we’ll go on with our lives.” I even suggested he take a Xanax, reassuring him his flight would be fine.

Now, in the nursing home, he reiterated his message: “You go on.” The repetition, delivered with labored effort, underscored its importance. It was clear that forming these specific words was a struggle, a breakthrough amidst the fog of disease that had clouded his once brilliant mind.

This was the same mind that knew every lyric to “American Pie” and belted it out on family road trips; the brain that could recall the name of every seashell, even the rarest, after countless spring breaks in Florida with my mother, his partner in shelling and life.

Carrie

Carrie

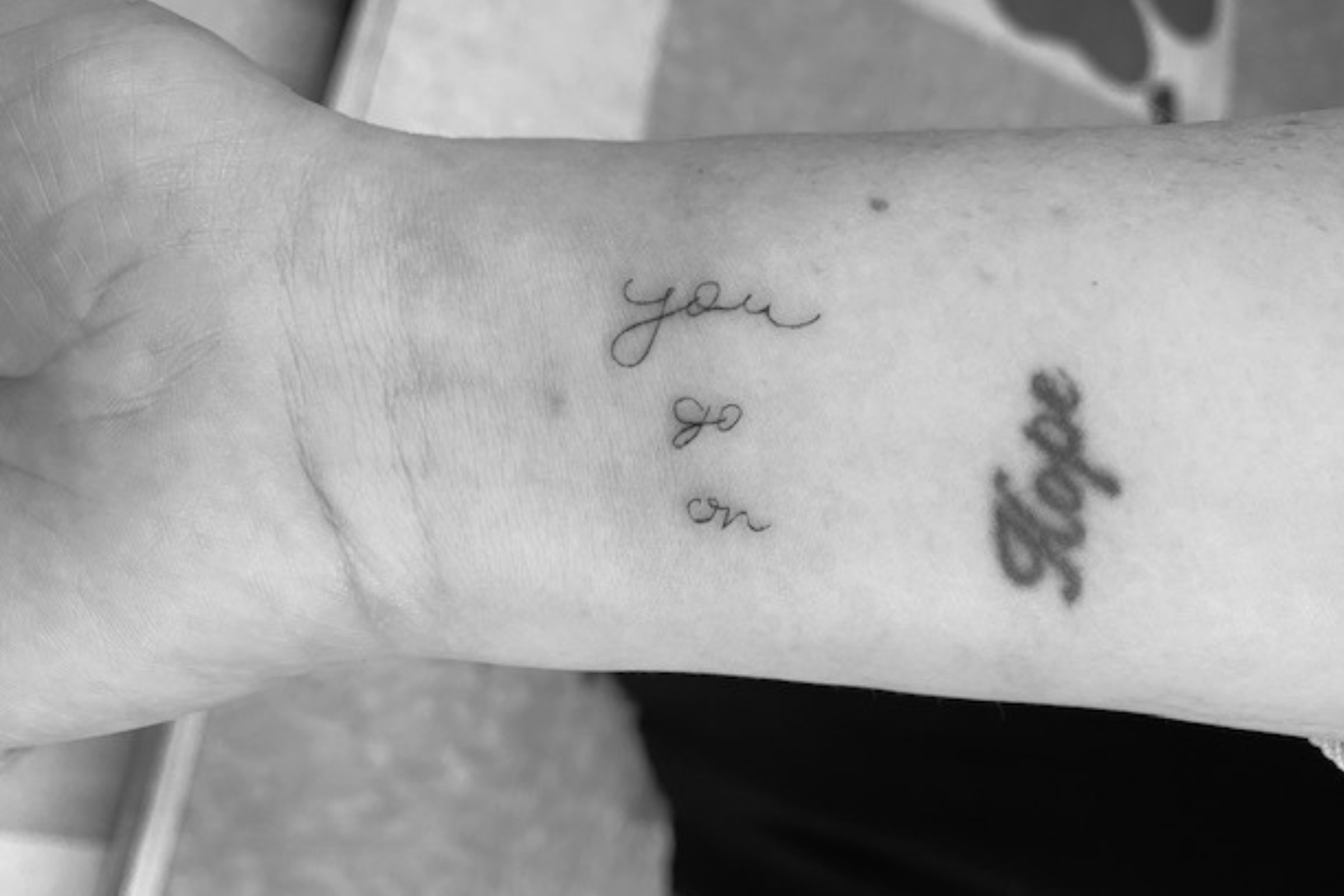

A close-up shot showcases Carrie Friedman Lloyd’s “dad tattoo,” featuring her father’s handwritten words, “You go on,” a poignant memorial inked on her inner wrist.

My father’s death was a slow, five-year goodbye. Yet, his passing in February still shattered our hearts anew.

In those first days of his absence, I felt adrift. Then, his enduring wish for us resonated: To go on. To live well.

Of course, I allowed myself to grieve, to feel the sharp pang of his loss. But I also embraced what I knew he wanted: to breathe easily, laugh freely, cherish family, walk along the beach, and sing loudly on road trips.

As the tattoo needle traced the second pass over “You go on” on my wrist, my shirt grew damp with sweat. I watched as the artist meticulously shaped the “O’s.”

The weeks spent tracing his handwriting had forged a renewed connection to him. His script mirrored mine – messy cursive, letters slanting downwards, as if our hands, like our spirits, sometimes grew weary.

My arm felt numb as the artist completed the dad tattoo. My wrist was red and tender, but there it was, etched in my father’s handwriting: You go on.

Words now imprinted forever, not just in my heart, but visibly on my skin – a constant reminder and a meaningful dad tattoo.