Polynesian tattoo art is a profound form of visual storytelling, deeply rooted in the rich cultural heritage of the islands of Polynesia. For centuries, these intricate Tattoo Patterns have served not merely as body decoration, but as powerful symbols of identity, status, lineage, and spiritual beliefs. This article delves into the fascinating world of Polynesian tattoo patterns, exploring their history, the artistry behind them, and the profound meanings woven into each design.

The Ancient Roots of Polynesian Tattooing

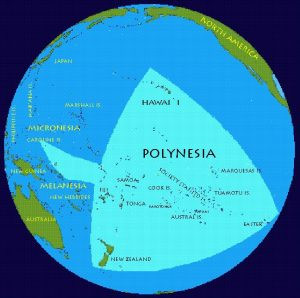

The origins of Polynesian society are still debated, but what is undeniable is that the term “Polynesia” encompasses a vast array of island nations and cultures, each contributing to the tapestry of Polynesian tattooing. These include the Marquesas, Samoa, Niue, Tonga, Cook Islands, Hawaii, Tahiti, and Maori, all linked to indigenous peoples from Southeast Asia. This expansive region, a sub-region of Oceania, is a triangle in the central and southern Pacific Ocean, with New Zealand, Hawaii, and Easter Island forming its points.

The Polynesian people, despite linguistic variations, share core cultural elements, with the ocean and spirituality deeply embedded in their worldview. Words like “moana” (ocean) and “mana” (spiritual force) resonate across Polynesian cultures, highlighting their reverence for the life-giving ocean.

polynesian triangle

polynesian triangle

Alt text: Polynesian Triangle map highlighting the vast region of Oceania, including Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand, showcasing the geographical spread of Polynesian tattoo patterns.

Tattoo Art as Language and Identity

In the absence of written language, tattoo patterns became the primary means of expression in ancient Polynesia. These weren’t random designs; they were carefully crafted narratives inscribed onto the skin. Tattoos communicated social standing within a hierarchical society, marked rites of passage like sexual maturity, traced genealogy, and indicated an individual’s place within their community. Virtually everyone in ancient Polynesian society bore tattoos, a testament to their cultural significance.

European contact began in 1595 with Spanish explorers reaching the Marquesas Islands. However, it was Captain James Cook’s voyages in the late 18th century that brought Polynesian culture, including their distinctive tattoos, to European attention. The word “tattoo” itself entered the European lexicon through Cook’s accounts of the Tahitian word “tattaw.” The arrival of a tattooed Tahitian man, Ma’i, in Europe further fueled fascination, and sailors quickly adopted Polynesian tattoo patterns, contributing to their spread across the continent.

While Polynesian tattooing boasts a history stretching back over 2000 years, the 18th century saw suppression attempts due to Old Testament prohibitions. A revival began in the 1980s, rekindling lost arts. However, concerns over sterilization with traditional tools led to a temporary ban on tattooing in French Polynesia in 1986, highlighting the challenges of preserving tradition in a modern context. Despite these obstacles, the dedication of scholars, artists, and researchers has been instrumental in the resurgence of Polynesian tattoo art, particularly in regions like Tonga.

Tonga and Samoa: Centers of Polynesian Tattoo Refinement

Tonga and Samoa emerged as key centers where Polynesian tattooing evolved into a highly sophisticated art form. Tongan warriors were extensively tattooed from waist to knees with geometric tattoo patterns, primarily triangles, bands, and solid black areas.

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson proudly displays for his large, traditional Polynesian tattoo

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson proudly displays for his large, traditional Polynesian tattoo

Alt text: Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson showcasing his Polynesian tattoo patterns, highlighting the contemporary popularity and enduring appeal of traditional designs.

The tattooing process in Tonga was deeply ritualistic, overseen by trained priests adhering to strict protocols and taboos. For Tongans, these tattoo patterns held profound social and cultural weight.

In Samoa, tattooing also played a crucial role in religious ceremonies and warfare. The tattoo artist held a hereditary and highly respected position, often tattooing groups in elaborate ceremonies attended by the community. Samoan warrior tattoos typically extended from the waist to below the knee. While less common, Samoan women also received tattoos, usually delicate, flower-like geometric tattoo patterns on hands and lower bodies.

Around 200 AD, Samoan and Tongan voyagers settled in the Marquesas, leading to the development of the Marquesan culture over centuries, known for its complex and elaborate tattoo patterns.

Marquesan Art: The Pinnacle of Polynesian Tattoo Complexity

Marquesan art, including architecture and especially tattoo designs, reached unparalleled levels of complexity within Polynesia. Marquesan tattoos frequently covered the entire body, showcasing intricate and detailed tattoo patterns.

Traditional Tools and Techniques: A Legacy Preserved

Remarkably, the tools and techniques used in Polynesian tattooing have remained largely unchanged over centuries. Traditional skill was passed down through generations, with each tattoo artist, or “tufuga,” undergoing years of apprenticeship.

Traditional Polynesian tattooing tools

Traditional Polynesian tattooing tools

Alt text: Traditional Polynesian tattooing tools, featuring handcrafted combs and mallets, illustrating the time-honored methods used to create intricate tattoo patterns.

The arrival of Christianity in Tonga led to the suppression of many indigenous practices, including tattooing, which was lost in Tonga but preserved in Samoa. In Samoa, the hand-tapping method has remained unbroken for over 2000 years. Apprentice artists in Samoa spent years practicing designs on sand or bark cloth using a “au,” a tattooing comb made of sharpened boar’s teeth attached to a turtle shell and wooden handle.

Enduring the Pain: A Testament to Cultural Devotion

Polynesian tattooing was an intensely painful process, carrying risks of infection. However, enduring the pain was a mark of courage and commitment to cultural traditions. Refusing tattoos was considered cowardly, leading to social ostracization. Men who abandoned the process bore a “mark of shame” for life.

The traditional Samoan “pe’a,” a full body tattoo from mid-torso to knees, was particularly demanding. Artists used a mallet to tap the ink-laden comb into the skin, guided by simple markings. Sessions lasted until dusk or until the recipient’s pain threshold was reached, sometimes taking months to complete with healing breaks. Upon completion, the family celebrated the man’s endurance with a feast, and the “tufuga” marked the ordeal’s end by smashing a water vessel at his feet.

The Healing Process and Long-Term Commitment

Healing was a lengthy process, often taking months. Tattooed skin was washed with salt water to prevent infection and massaged to remove impurities. Family and friends assisted, as even basic movements could irritate the inflamed skin. While the tattoo patterns became visible within six months, full healing could take almost a year, highlighting the profound commitment involved in receiving a traditional Polynesian tattoo.

Body Placement: Meaning in Location

Body placement is crucial in Polynesian tattooing, adding layers of meaning to the tattoo patterns. Polynesian cosmology views humans as descendants of Rangi (Heaven) and Papa (Earth). The body is seen as a bridge between these realms, with the upper body linked to spirituality and the heavens, and the lower body to the earthly realm.

Placements like genealogy tracks on the back of arms suggest associations of the back with the past and the front with the future. Gender symbolism also exists, with left often associated with women and right with men.

Alt text: Polynesian tattoo body placement guide, illustrating the symbolic associations of different body areas with concepts like spirituality, strength, and life energy, influencing the meaning of tattoo patterns.

Here’s a breakdown of body area symbolism in relation to tattoo patterns:

- Head: Contact point with Rangi, symbolizing spirituality, knowledge, wisdom, and intuition.

- Higher Trunk (Chest): Area between navel and chest, representing generosity, sincerity, honor, and reconciliation, bridging Heaven and Earth.

- Lower Trunk (Stomach & Thighs): From thighs to navel, related to life energy, courage, procreation, independence, and sexuality. Thighs symbolize strength and marriage, the stomach is the origin of “mana,” and the navel represents independence.

- Upper Arms and Shoulders: Associated with strength and bravery, linked to warriors and chiefs. The Maori term “kikopuku” emphasizes the idea of strong, swollen arms.

- Lower Arms and Hands: Represent creativity, creation, and making.

- Legs and Feet: Symbolize moving forward, transformation, progress, separation, and choice. Feet, in contact with Papa (Earth), relate to concreteness and material matters.

- Joints: Represent union and connection. Joints further from the head symbolize more distant kinship or lower status. Ankles and wrists signify ties and commitment, while knees relate to chiefs (kneeling in respect).

Important Note: While traditional placement provides context, personal meaning should always be prioritized. Tattoo patterns should resonate with the wearer above all else.

Polynesian Tattoo Motifs and Their Meanings

Polynesian tattoo patterns are built from a rich vocabulary of motifs, each carrying specific symbolic weight. Here are some key examples:

-

Enata (Singular): Human figures representing people, men, women, and sometimes gods. They symbolize relationships and can represent defeated enemies when inverted.

-

Enata (Pattern):

Alt text: Enata pattern tattoo motif, showcasing stylized human figures linked together, representing ancestors guarding descendants or symbolizing the cloudy sky (“ani ata”).

Stylized enata in a row, holding hands, form the “ani ata” motif, meaning “cloudy sky.” Semi-circular rows of enata also represent the sky and ancestral protection.

-

Shark Teeth (Simplified): “Niho mano” – shark teeth – represent protection, guidance, strength, and ferocity. Sharks are revered as forms that “aumakua” (spirit guides) may take. They also symbolize adaptability.

-

Shark Teeth (Complex):

Alt text: Complex shark teeth tattoo pattern, demonstrating a stylized representation of “niho mano,” symbolizing strength, protection, and adaptability in Polynesian tattoo art.

More elaborate stylizations of shark teeth are frequently incorporated into tattoo patterns.

-

Spearhead: Represents warrior spirit and sharpness, also symbolizing the sting of certain animals.

-

Spearhead (Pattern):

Alt text: Spearhead pattern tattoo motif, a row of stylized spearheads symbolizing courage, protection, and the warrior spirit in traditional Polynesian designs.

Rows of spearheads are a common tattoo pattern variation.

-

Ocean (Simplified): The ocean is central to Polynesian life and mythology, representing the final resting place and the source of sustenance. It can symbolize death and the afterlife.

-

Ocean (Waves):

Alt text: Ocean wave tattoo pattern, a stylized depiction of waves representing life, change, continuity, and the journey to the afterlife in Polynesian symbolism.

Stylized ocean waves symbolize life, change, continuity, and the journey to the afterlife.

- Tiki:

tiki

tiki

Alt text: Tiki tattoo motif, depicting a human-like figure representing semi-gods, deified ancestors, and guardians, symbolizing protection and fertility in Polynesian tattoo art.

“Tiki” refers to human-like figures representing semi-gods, deified ancestors, priests, and chiefs. They symbolize protection, fertility, and guardianship. A simplified version, the “brilliant eye,” emphasizes eyes, nostrils, and ears.

-

Tiki Eyes: Often featured prominently, tiki eyes can be depicted in front view, sometimes with a protruding tongue symbolizing defiance.

-

Turtle:

turtle

turtle

Alt text: Turtle tattoo motif, or “honu,” symbolizing health, longevity, peace, foundation, unity, and family connection across Polynesian cultures.

The turtle, or “honu,” symbolizes health, fertility, longevity, foundation, peace, and unity. “Hono” in Marquesan also means joining and stitching together families. Upward-facing turtles do not inherently represent taking souls to the afterlife; a human figure on or near the shell conveys that meaning.

-

Turtle Shell Pattern: Shell patterns are derived from the turtle shell, creating distinct tattoo patterns.

-

Lizard:

lizard

lizard

Alt text: Lizard tattoo motif, also known as “mo’o” or “moko,” representing gods, good luck, communication with the divine, and both positive and negative omens in Polynesian mythology.

Lizards and geckos, “mo’o” or “moko,” are significant in Polynesian myth. Gods and spirits often appear as lizards, which are seen as powerful creatures bringing good luck, facilitating communication with gods, and accessing the spiritual realm. However, they can also bring misfortune if disrespected.

-

Lizard Pattern: Stylized lizard patterns closely resemble human figure patterns (“enata”).

-

Stingray:

stingray

stingray

Alt text: Stingray tattoo motif, symbolizing protection, adaptation, gracefulness, peacefulness, agility, speed, and stealth, reflecting the stingray’s ability to hide and defend itself.

Stingrays symbolize protection, adaptation, gracefulness, peacefulness, agility, speed, and stealth, stemming from their ability to hide from predators in the sand.

Specializing in Polynesian and Maori Tattoo Artwork

Alt text: Polynesian arm tattoo pattern example, showcasing the artistry and detail achievable in contemporary Polynesian tattoo designs, linking to a Polynesian tattoo gallery.

If you are captivated by the artistry and meaning of Polynesian tattoo patterns, explore our Polynesian Tattoo Gallery for further inspiration or contact us to discuss your own unique tattoo ideas.

Source: The Polynesian Tattoo Handbook

Alt text: Tattoo art graphic, a stylized image representing the transformative and personal nature of tattoo art, inviting viewers to consider a custom tattoo design.

Discover a unique art form tailored to you, applied with the highest professional standards. Stand out with a striking Polynesian tattoo.

Polynesian-Arm-2

Polynesian-Arm-2