Around two years ago, I got my first tattoos. This personal milestone sparked a deeper interest in the world of body art and its historical intersections with beauty and culture. It also led me to reflect on a vintage makeup brand I’d encountered previously: Tattoo. Alongside its sister line, Savage, Tattoo cosmetics immediately captivated me with their striking imagery – visuals that were as unsettling as they were alluring. I acquired some vintage advertisements and product containers, initially considering them for a summer exhibition due to their tropical aesthetic. However, closer examination revealed a darker, more problematic story that shifted my perspective. Let’s delve into why these vintage “Tattoo Makeup” brands are far more complex than their exotic packaging suggests.

The illustrator behind some of the early Tattoo advertisements remains unidentified, the signature obscured and lost to time. Despite this anonymity, the visual language speaks volumes.

Unidentified artist's 1934 Tattoo lipstick advertisement featuring a woman with dark hair and a flower, with faded text in the background

Unidentified artist's 1934 Tattoo lipstick advertisement featuring a woman with dark hair and a flower, with faded text in the background

Another 1934 Tattoo lipstick advertisement, similar to the first, with a focus on the exotic imagery and faded text

Another 1934 Tattoo lipstick advertisement, similar to the first, with a focus on the exotic imagery and faded text

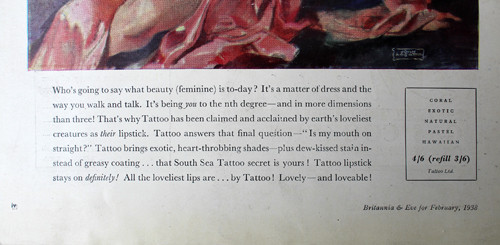

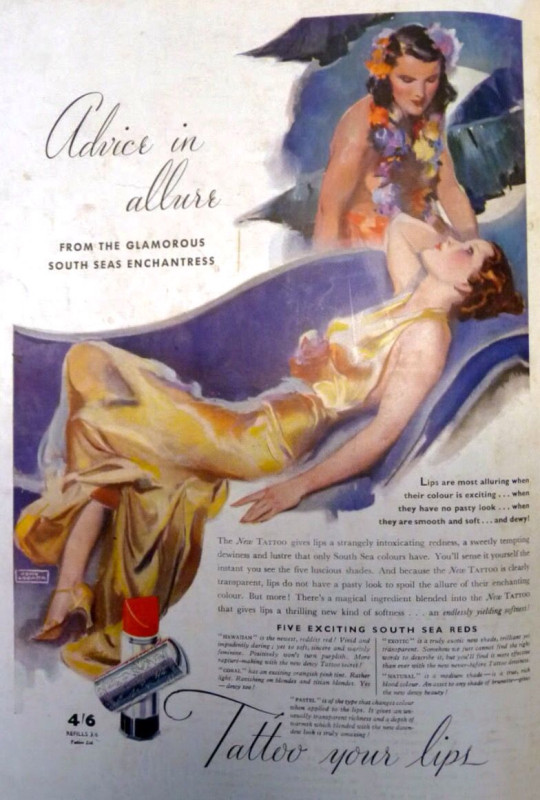

In contrast, the artistry of John LaGatta (1894-1977), a recognized illustrator, is evident in other Tattoo advertisements. His signature style and the use of British English spelling (“colour”) in the publication clearly place these ads in a different context, likely a British magazine from 1938.

John LaGatta's 1938 Tattoo lipstick advertisement for a British magazine, showcasing his distinctive style and the word "colour"

John LaGatta's 1938 Tattoo lipstick advertisement for a British magazine, showcasing his distinctive style and the word "colour"

A second 1938 Tattoo lipstick advertisement by John LaGatta, continuing the brand's exotic theme and his recognizable artistic approach

A second 1938 Tattoo lipstick advertisement by John LaGatta, continuing the brand's exotic theme and his recognizable artistic approach

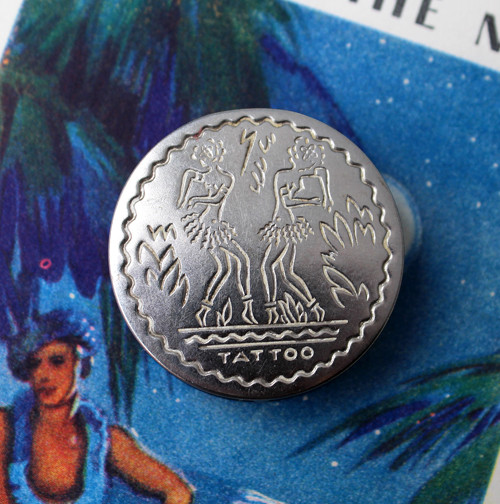

The product packaging itself echoes the exotic themes promoted in the advertisements. The lipstick cases and rouge containers are adorned with imagery intended to evoke a sense of the “primitive” and “untamed.”

Close-up of a vintage Tattoo lipstick case, revealing the brand's thematic design

Close-up of a vintage Tattoo lipstick case, revealing the brand's thematic design

Another view of a Tattoo lipstick, highlighting the packaging details and vintage aesthetic

Another view of a Tattoo lipstick, highlighting the packaging details and vintage aesthetic

A vintage Tattoo rouge compact, showcasing the brand's design elements on the compact case

A vintage Tattoo rouge compact, showcasing the brand's design elements on the compact case

Another example of a Tattoo rouge compact, emphasizing the brand's consistent visual identity across its product line

Another example of a Tattoo rouge compact, emphasizing the brand's consistent visual identity across its product line

Compared to modern blush compacts, the Tattoo rouge is notably small, a common characteristic of vintage cosmetics. This diminutive size reflects the makeup trends and product formulations of the era.

A Tattoo rouge product shown to emphasize its small size relative to contemporary blush products

A Tattoo rouge product shown to emphasize its small size relative to contemporary blush products

Even the rouge puff was branded, imprinted with the same distinctive Tattoo design, demonstrating attention to detail in branding even for ancillary components.

A Tattoo rouge puff imprinted with the brand's logo, illustrating the comprehensive branding efforts

A Tattoo rouge puff imprinted with the brand's logo, illustrating the comprehensive branding efforts

Interestingly, some Tattoo rouge compacts featured “U.S.A.” inscribed beneath the brand name, while others did not. This subtle variation likely indicates minor production changes rather than significant design alterations.

A Tattoo rouge compact with "U.S.A." inscription, pointing out a variation in the product branding

A Tattoo rouge compact with "U.S.A." inscription, pointing out a variation in the product branding

Further examination reveals differences in the compact bottoms, with some having inscriptions and others being plain. These variations likely reflect manufacturing nuances and do not suggest distinct product lines.

Comparison of Tattoo rouge compact bottoms, highlighting the manufacturing differences

Comparison of Tattoo rouge compact bottoms, highlighting the manufacturing differences

An alternate design for Tattoo lipstick and rouge also surfaced, possibly representing a mini version or a design variation sold concurrently with the more common packaging. This suggests an evolution or diversification in the brand’s product presentation.

Alternate design Tattoo lipstick, showcasing a less common packaging style

Alternate design Tattoo lipstick, showcasing a less common packaging style

Alternate design Tattoo rouge compact, complementing the lipstick's less frequent packaging design

Alternate design Tattoo rouge compact, complementing the lipstick's less frequent packaging design

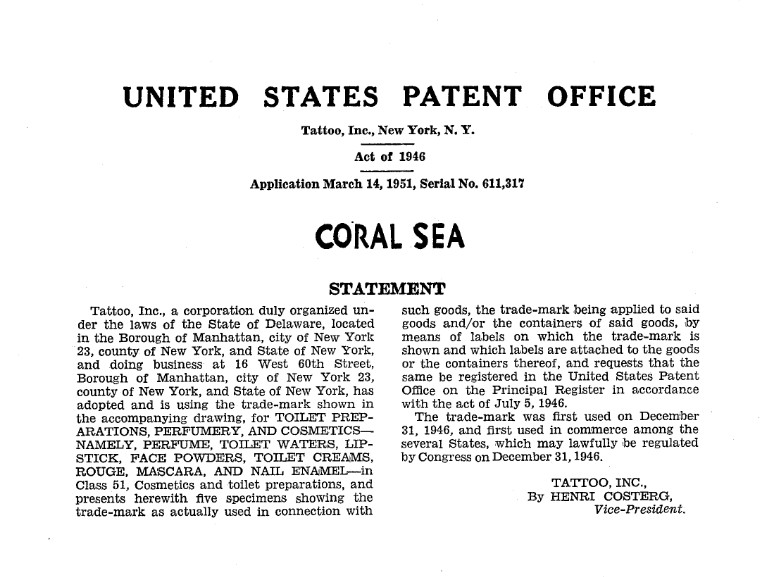

This alternate design appeared in a 1947 advertisement, hinting that it might have emerged towards the end of the Tattoo brand’s lifespan. However, the shade “Coral Sea,” trademarked in 1946, was associated with this packaging, complicating the timeline.

1947 Tattoo lipstick advertisement featuring the alternate design, indicating its presence late in the brand's history

1947 Tattoo lipstick advertisement featuring the alternate design, indicating its presence late in the brand's history

My own Tattoo lipstick in “Coral Sea” and its trademark patent further illustrate the product line’s details and historical context.

Tattoo lipstick in Coral Sea shade, providing a real-world example of the product and shade name

Tattoo lipstick in Coral Sea shade, providing a real-world example of the product and shade name

Tattoo Coral Sea patent document, offering official documentation of the shade trademark and brand history

Tattoo Coral Sea patent document, offering official documentation of the shade trademark and brand history

I also possess a Savage powder box, a brand related to Tattoo. Savage, with its even more overtly problematic name and marketing, was featured in a previous post and exhibition, a decision I now view with regret due to its deeply offensive nature.

Vintage Savage blush, showing the brand's packaging and name, highlighting its problematic connotations

Vintage Savage blush, showing the brand's packaging and name, highlighting its problematic connotations

Another vintage Savage blush product, reinforcing the brand's visual and naming themes

Another vintage Savage blush product, reinforcing the brand's visual and naming themes

Research, including insights from Collecting Vintage Compacts and newspaper advertisements, reveals that both Tattoo and Savage were launched in the early 1930s by James Leslie Younghusband. Younghusband, a former stunt pilot turned businessman, was also the mind behind Kissproof, another “indelible” lipstick line from the 1920s. Despite Kissproof’s continued sales and questionable ingredients, Younghusband introduced Tattoo and Savage, both marketed as long-wearing and comfortable, with seemingly little differentiation in formula.

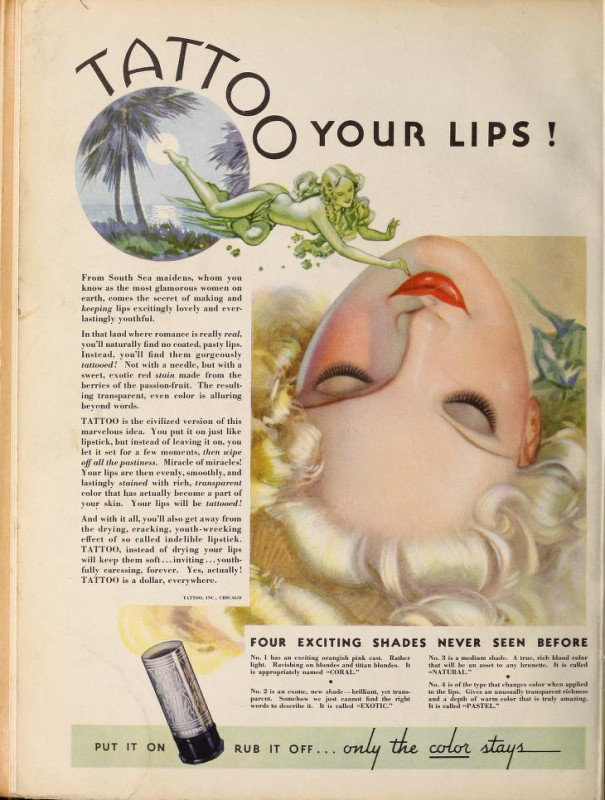

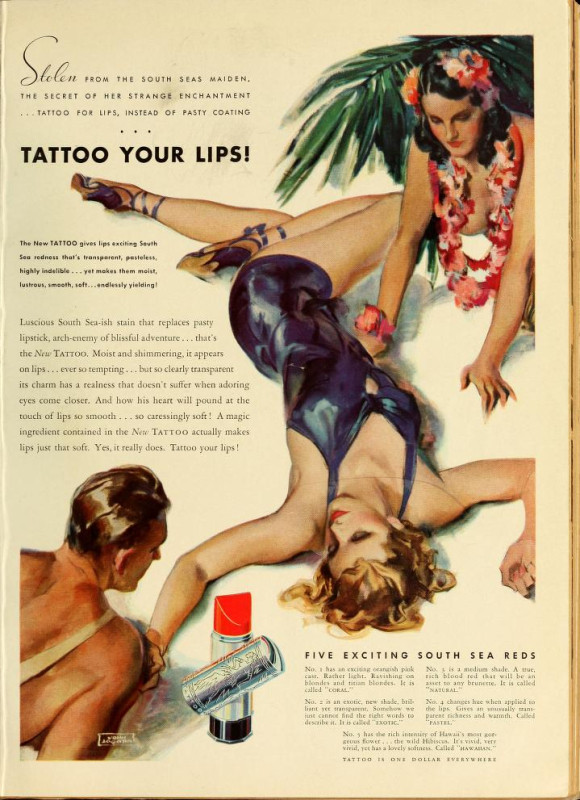

The most glaring issue with Tattoo and Savage lies in their deeply racist advertising. In today’s world, the overt fetishization of “exotic” cultures and people in these campaigns would be utterly unacceptable. The ads, while visually striking, rely on racist tropes and cultural appropriation, depicting “native” women as hyper-sexualized and “uncivilized” to sell makeup to white women. The advertising copy explicitly links the lipstick shades to the supposed beauty secrets of “South Sea maidens,” claiming Tattoo lipstick is a “civilized version” of their “exotic red stain.”

1935 Tattoo lipstick advertisement with racist copy claiming inspiration from "South Sea maidens" and their "gorgeously tattooed" lips

1935 Tattoo lipstick advertisement with racist copy claiming inspiration from "South Sea maidens" and their "gorgeously tattooed" lips

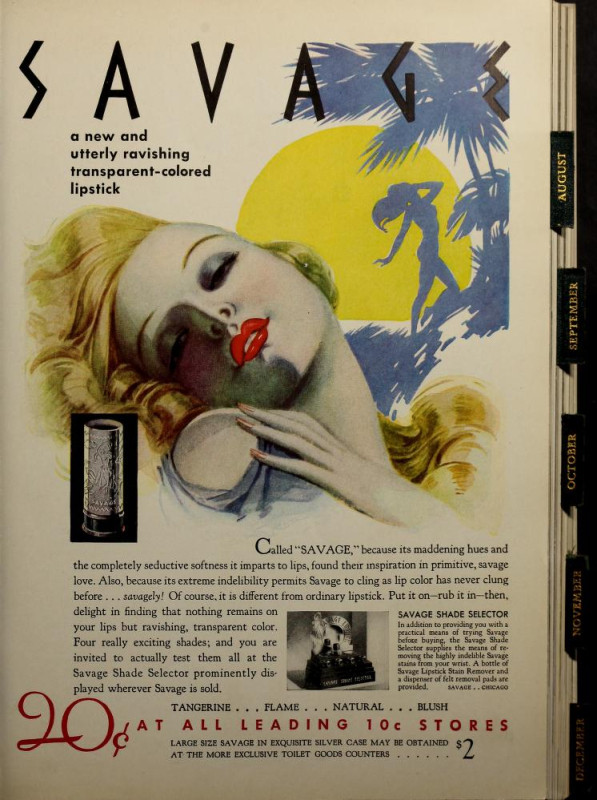

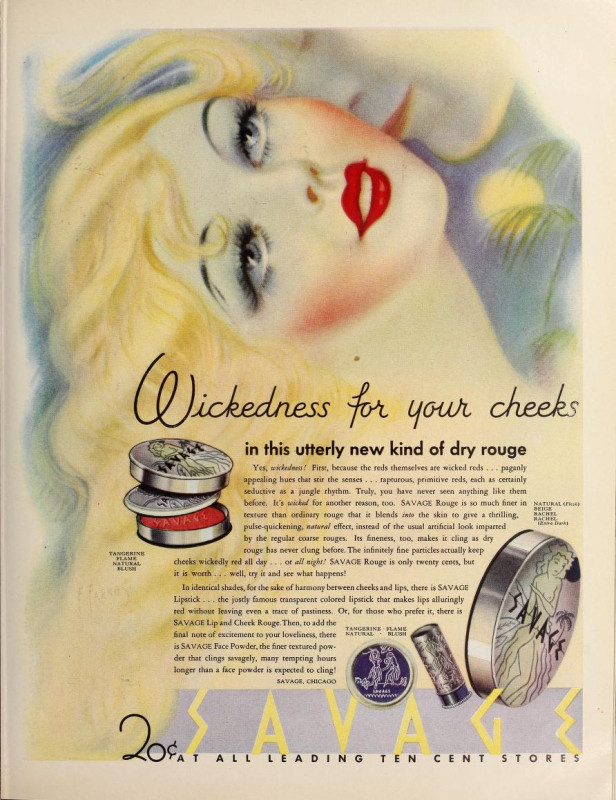

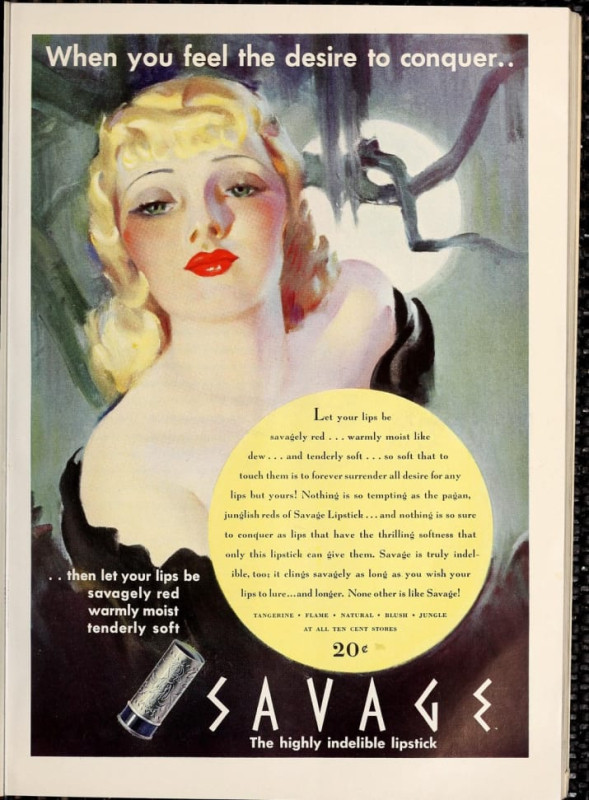

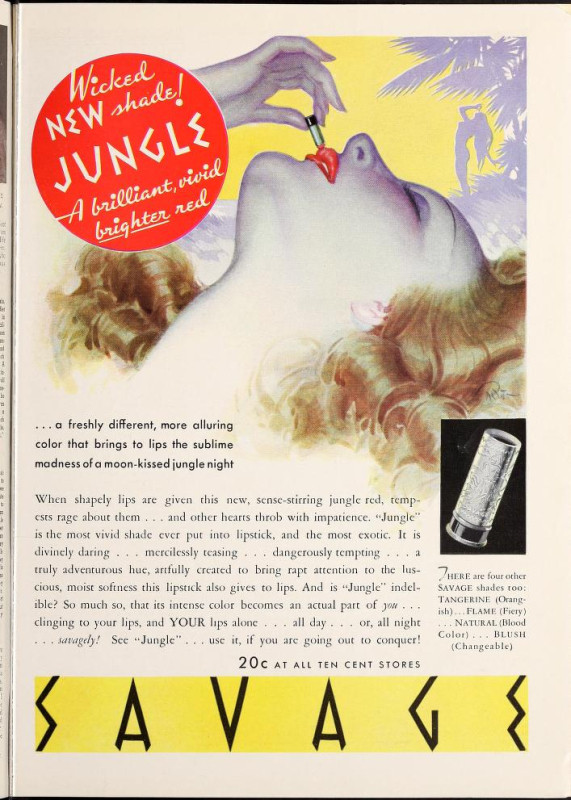

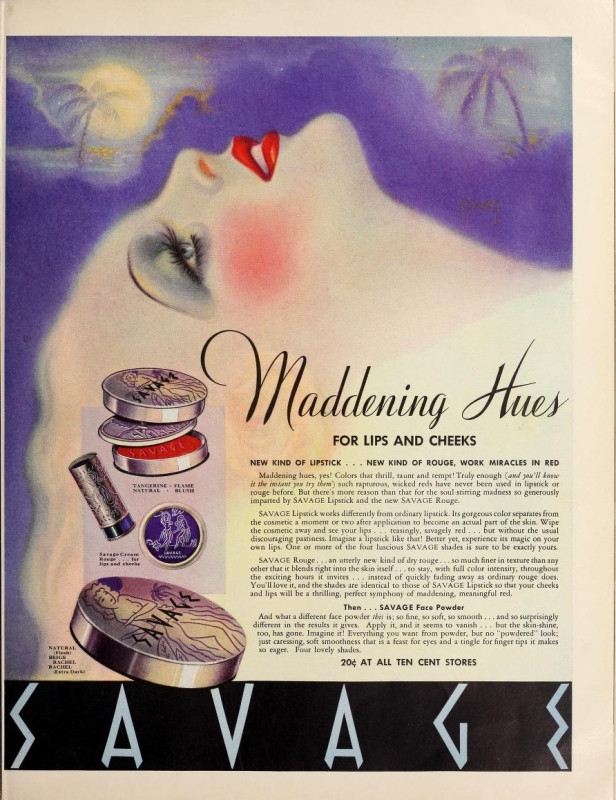

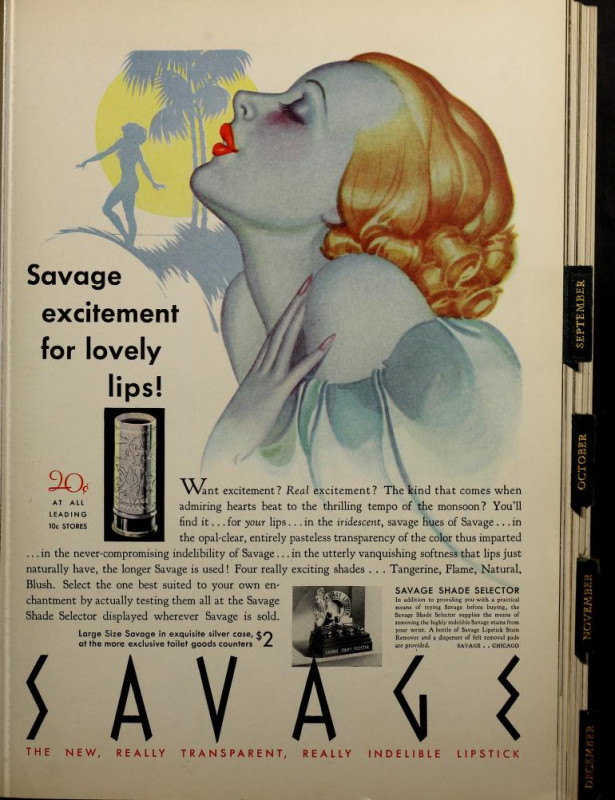

Savage’s racism is even more explicit, associating its colors with “primitive, savage love” and “paganly appealing hues.” The brand directly connects “wickedness” and “seduction” with indigenous cultures, reinforcing harmful stereotypes.

1934 Savage lipstick advertisement overtly using racist language associating its colors with "primitive, savage love"

1934 Savage lipstick advertisement overtly using racist language associating its colors with "primitive, savage love"

1935 Savage advertisement linking "wickedness" and "primitive reds" to indigenous cultures in its racist marketing

1935 Savage advertisement linking "wickedness" and "primitive reds" to indigenous cultures in its racist marketing

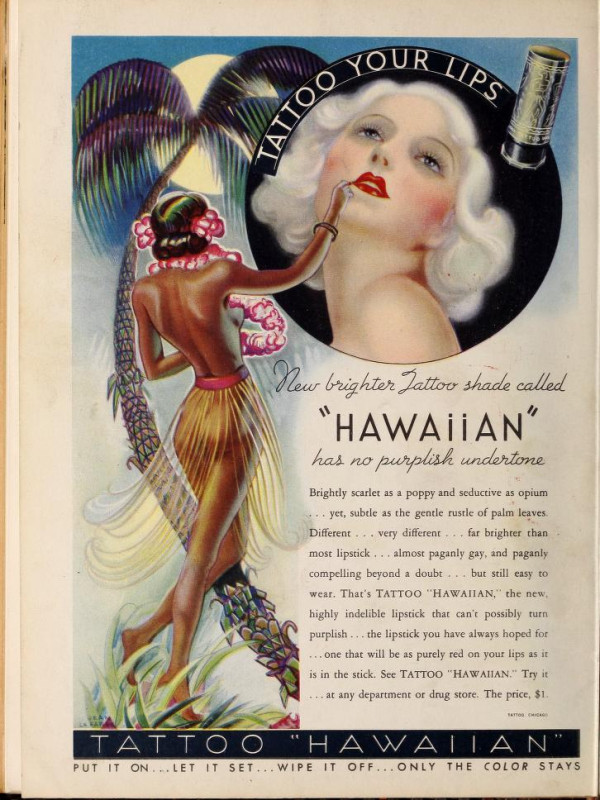

Tattoo ads frequently depict tan-skinned women in stereotypical and often topless attire, serving as decorative props for white women, perpetuating racist power dynamics. These images borrow from a long history of objectifying women of color in Western art and media.

1935 Tattoo lipstick advertisement featuring topless, dark-skinned women serving as props in a racist depiction

1935 Tattoo lipstick advertisement featuring topless, dark-skinned women serving as props in a racist depiction

Tattoo advertisement showcasing the brand's racist imagery and objectification of women of color

Tattoo advertisement showcasing the brand's racist imagery and objectification of women of color

Another Tattoo advertisement reinforcing racist stereotypes and the brand's problematic visual language

Another Tattoo advertisement reinforcing racist stereotypes and the brand's problematic visual language

1937 Tattoo lipstick advertisement continuing the brand's pattern of racist and culturally appropriative imagery

1937 Tattoo lipstick advertisement continuing the brand's pattern of racist and culturally appropriative imagery

1936-37 Tattoo advertisement further demonstrating the brand's reliance on racist and stereotypical depictions

1936-37 Tattoo advertisement further demonstrating the brand's reliance on racist and stereotypical depictions

Another LaGatta Tattoo ad reinforces these themes, further embedding the racist imagery within the brand’s marketing.

1937 Tattoo advertisement by LaGatta, maintaining the brand's racist and culturally insensitive approach

1937 Tattoo advertisement by LaGatta, maintaining the brand's racist and culturally insensitive approach

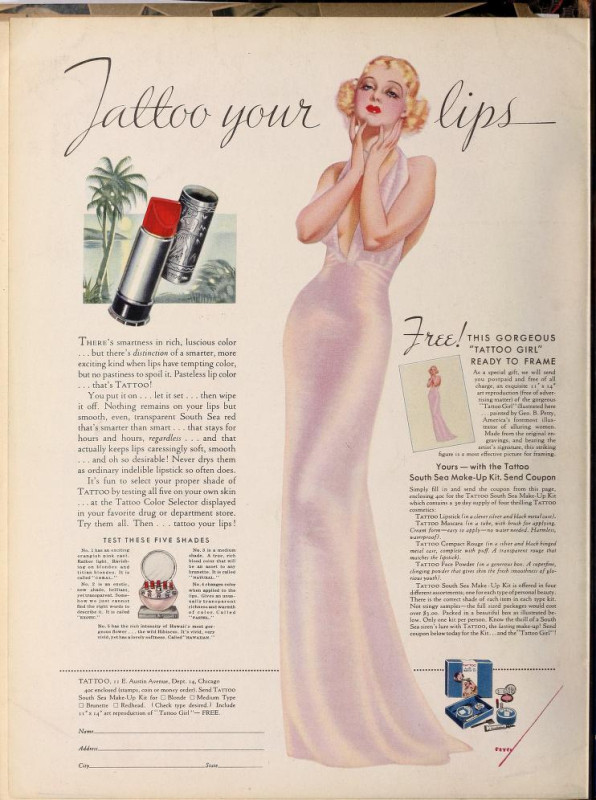

Ironically, the ideal “Tattoo girl,” as depicted in another ad, was white and blonde, highlighting the brand’s target demographic and further underscoring the racist implications of its marketing.

1936 Tattoo advertisement depicting a white blonde woman as the ideal "Tattoo girl," contrasting with the brand's exoticized imagery

1936 Tattoo advertisement depicting a white blonde woman as the ideal "Tattoo girl," contrasting with the brand's exoticized imagery

Savage ads, too, incorporated colonialist language, using words like “conquer,” further associating the brand with problematic historical power dynamics.

Savage advertisement employing colonialist language like "conquer," adding to the brand's racist marketing approach

Savage advertisement employing colonialist language like "conquer," adding to the brand's racist marketing approach

Savage advertisement continuing the brand's pattern of racist and culturally insensitive marketing tactics

Savage advertisement continuing the brand's pattern of racist and culturally insensitive marketing tactics

Why did Younghusband choose this marketing approach? In the competitive 1930s indelible lipstick market, dominated by brands like Tangee, Tattoo and Savage likely aimed to stand out through risqué and racist imagery. By portraying indigenous South Pacific cultures as “feral” and “untamed,” and offering white women a way to access this imagined freedom through lipstick, the brands carved a niche, albeit a deeply problematic one. The ads emphasize “thrilling,” “maddening,” and long-lasting color, suggesting a product that could withstand passionate encounters and “late-night activity.”

1936-37 Tattoo lipstick advertisement using suggestive language and themes to market its product

1936-37 Tattoo lipstick advertisement using suggestive language and themes to market its product

1935 Savage Dry Rouge advertisement employing similar suggestive and potentially racist marketing techniques

1935 Savage Dry Rouge advertisement employing similar suggestive and potentially racist marketing techniques

1935 Savage advertisement continuing the brand's pattern of suggestive and culturally insensitive marketing

1935 Savage advertisement continuing the brand's pattern of suggestive and culturally insensitive marketing

1934 Savage lipstick advertisement utilizing similar marketing strategies with racist undertones

1934 Savage lipstick advertisement utilizing similar marketing strategies with racist undertones

The rise of tourism to Hawaii and other South Pacific islands in the 1930s likely also influenced this marketing direction. Tropical themes were popular, and Tattoo and Savage tapped into this cultural fascination, albeit through a racist lens.

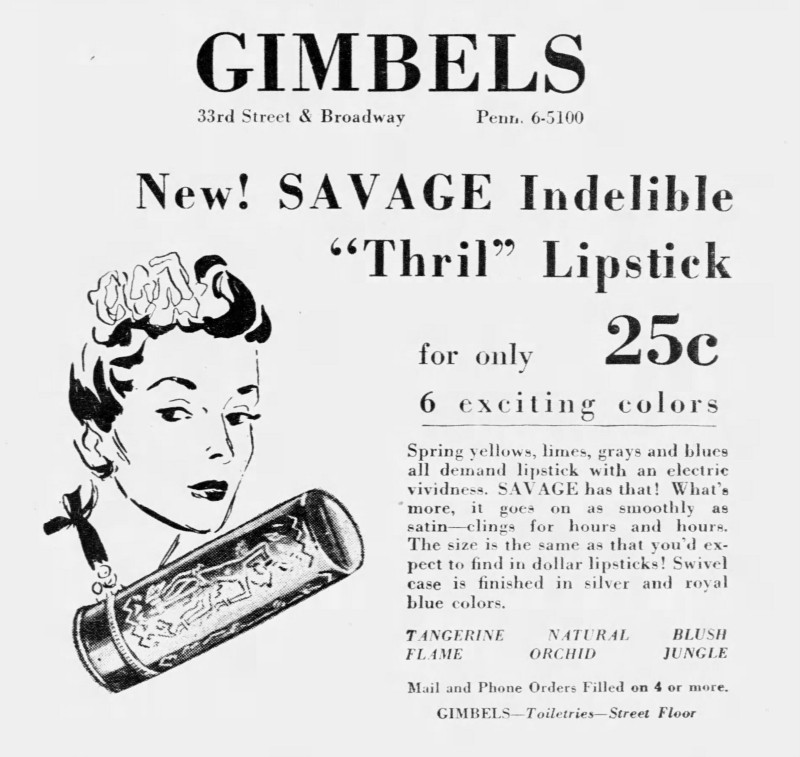

The distinction between Tattoo and Savage and the reason for launching both brands remains unclear. Despite price differences (Tattoo at one dollar, Savage at 20 cents), both were sold in department stores, as evidenced by a 1939 Gimbel’s ad for Savage. There seems to be no significant product differentiation, adding to the mystery of the dual-brand strategy.

1939 Savage lipstick newspaper advertisement from Gimbel's department store, indicating its retail placement

1939 Savage lipstick newspaper advertisement from Gimbel's department store, indicating its retail placement

Finally, the question remains: why acquire and discuss such racist items for a museum? It’s a difficult question. While I am acutely aware of the problematic nature of these brands and their advertising, I believe they hold historical significance. They serve as tangible examples of the racism prevalent in the beauty industry’s past. While not suitable for celebratory exhibitions, these items are crucial for fostering dialogue about the darker aspects of beauty history. A cosmetics museum should not shy away from uncomfortable truths but use them as opportunities for learning and critical reflection. My aim is to create a museum that is primarily a place of beauty and wonder, but also one that acknowledges and confronts the problematic elements within the world of cosmetics.

These vintage “tattoo makeup” brands, with their racist marketing and cultural appropriation, offer a stark reminder of the beauty industry’s complex and sometimes ugly history. Examining them allows us to understand the evolution of beauty standards, advertising practices, and societal attitudes, and to engage in critical conversations about representation and ethics in the beauty world today. Further research into James Leslie Younghusband and the Tattoo and Savage brands promises to shed more light on their story and their place within the history of cosmetics.