Lisbeth Salander, the enigmatic heart of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy, is more than just a character; she’s an indelible mark on modern literature and cinema. Like a complex tattoo, her story in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo is layered with intricate details, striking imagery, and a lingering impact. This isn’t just a crime thriller; it’s a deep dive into a character as permanent and fascinating as ink on skin. We explore how this compelling narrative, this ‘Tattoo Book’ in its metaphorical richness, translates across mediums, comparing the original novel with its Swedish and American film adaptations.

Just as a tattoo tells a story on the body, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo book unfolds a narrative that grips you from the first page. We are introduced to Lisbeth Salander, a fiercely independent and formidably intelligent hacker, marked by her gothic appearance and deeply ingrained distrust of abusive men – a hostility born from witnessing her father’s violence against her mother. This traumatic past leads to her being declared legally incompetent after she retaliates against her father, setting the stage for a character defined by resilience and a thirst for justice. Before the central mystery even begins, we understand Lisbeth is no ordinary protagonist; she’s a figure etched in trauma and brilliance.

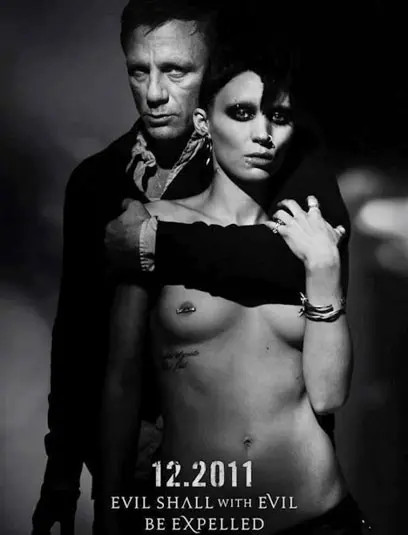

When considering The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo as a ‘tattoo book’, we must acknowledge the multiple interpretations that arise when adapting such a rich text. We are presented not just with Larsson’s literary Lisbeth, but also Noomi Rapace’s visceral portrayal in the Swedish film and Rooney Mara’s nuanced take in David Fincher’s American remake. While each iteration captures the essence of Salander, subtle differences in character and narrative create distinct impressions. The challenge, much like choosing a tattoo design from a book, is discerning which version resonates most deeply.

Let’s first revisit the source, the ‘tattoo book’ itself. As a complex mystery, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo novel, in my own words, immerses us in a “locked room” puzzle. It pairs the determined journalist Mikael Blomkvist with the socially unconventional Lisbeth Salander. Together, they unravel a decades-old disappearance, exposing a dark history of serial murder and sexual abuse.

My initial impression of the novel highlighted its genre roots, acknowledging that despite its hype, Dragon Tattoo remains a well-executed genre novel. It delivers the procedural elements expected of a mystery while maintaining remarkable readability. The pages turn effortlessly, drawing the reader into the investigation. While some plot points, particularly the final revelations and religious undertones, felt somewhat stretched, the compelling characters, especially Salander, left a lasting impression, hinting at stories yet untold beyond the immediate plot. This is the mark of a good ‘tattoo book’ – it leaves you wanting more, its characters and themes etched in your mind.

However, the novel is not without its complexities. Larsson’s detailed exposition, particularly on Swedish finance laws and political history, can be dense, potentially deterring some readers. Fortunately, film adaptations wisely streamline these elements, recognizing that cinematic storytelling demands a different pace. Despite these textual intricacies, the book’s page-turning quality remains undeniable. While some might critique the prose as clunky, its narrative drive is potent. This raw, unfiltered quality, much like the bold lines of a striking tattoo, contributes to its unique appeal.

Even with the novel’s imperfections, the prospect of seeing Lisbeth’s story visually realized was enticing. History shows that imperfect books can inspire exceptional films (The Godfather being a prime example). My experience with the Swedish film adaptation, viewed shortly after reading the book, left me somewhat underwhelmed. While Noomi Rapace’s portrayal of Lisbeth was undeniably powerful, the film felt slow-paced, struggling to translate the book’s research-heavy narrative into engaging cinema. It felt like a faithful rendition, but lacked a certain spark.

The announcement of David Fincher directing the English-language remake sparked considerable excitement. Fincher’s ability to create tension and visual dynamism, even in detail-oriented narratives like Zodiac (a film where research becomes captivating), suggested he could inject the necessary energy into Dragon Tattoo. Furthermore, the promise of a revised ending heightened anticipation, offering hope for a more impactful climax than the book’s conclusion.

Reports indicated that screenwriter Steven Zaillian had significantly altered the narrative, making Blomkvist less promiscuous, Salander more assertive, and, crucially, changing the ending. This deviation from the source material, while potentially controversial, promised a fresh and potentially improved cinematic experience. Coupled with Fincher’s directorial prowess, fresh off the success of The Social Network, the remake held immense potential.

Opening night arrived with high expectations. Ignoring minor pre-show distractions, the film began powerfully. The opening credits, a monochrome visual assault set to Karen O’s intense score, immediately established a dark, unsettling tone. This gave way to the familiar world of snow-covered Sweden, pressed flowers, piercings, and leather – Lisbeth’s world. Fincher’s meticulous direction revitalized these familiar elements, and Rooney Mara’s portrayal of Lisbeth was a revelation. She embodied damaged vulnerability, sparking a desire to understand and connect with her, a connection that mirrored Blomkvist’s journey in the story. The soundtrack by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross further enhanced the atmosphere, creating a pervasive sense of unease and intrigue. The film’s runtime of nearly three hours flew by, a testament to its immersive quality.

Despite the film’s strengths, a sense of dissatisfaction lingered after the initial viewing. Perhaps expectations were too high, but Fincher’s remake didn’t entirely resolve the inherent issues of the source material. Post-viewing discussions with friends sought to pinpoint the exact shortcomings.

One immediate realization was that the promised “completely changed ending” was somewhat overstated. The anticipation had been for a radical departure, but the actual differences were subtle. To clarify these nuances, a revisiting of the book and the Swedish film became necessary. Afterwards, a second viewing of the Fincher remake followed, all in an effort to solidify impressions before disparate details blurred.

The Swedish film, directed by Niels Arden Oplev, emerged from this comparative analysis as a stronger work than initially perceived. It retained crucial details absent in Fincher’s version, such as the foreshadowing of Lisbeth’s attempted patricide. While the first novel’s extent of this revelation is debatable, Oplev’s film incorporates flashbacks, culminating in a full reveal. Fincher’s film relegates this critical backstory to a brief, almost casual mention during pillow talk between Lisbeth and Blomkvist, a missed opportunity for deeper character exploration.

The Swedish film also presents a more nuanced portrayal of Blomkvist’s relationships. While not as overtly promiscuous as in the book, he is less emotionally restrained than Daniel Craig’s interpretation. The novel provides extensive context for Mikael’s relationship with Erika Berger, Millennium‘s co-owner, making their renewed intimacy understandable. In Fincher’s film, this reconnection feels abrupt, creating a sense of betrayal for the audience invested in Lisbeth and Mikael’s burgeoning bond. The Swedish film, conversely, omits Lisbeth’s jealousy, focusing instead on her reactive distancing from Blomkvist, driven by fear and self-preservation.

Another significant divergence lies in how Blomkvist obtains the crucial evidence against Wennerstrom. In all three versions, Lisbeth ultimately provides this information. However, both the book and Fincher’s film include a detail missing from the Swedish adaptation: Henrik Vanger promises Blomkvist evidence against Wennerstrom in exchange for investigating Harriet’s disappearance. This evidence proves initially useless due to the statute of limitations, highlighting Lisbeth’s crucial intervention. Oplev’s film omits this initial promise, weakening Blomkvist’s initial motivation for taking on the Vanger case. While this elevates Lisbeth’s role, it diminishes Blomkvist’s agency, making him appear less driven and more reactive – a weaker narrative choice for a protagonist.

Blomkvist’s childhood connection to Harriet and Anita Vanger is another subtle yet significant detail. Present in the novel and amplified in Oplev’s film (emphasizing the cousins’ resemblance), this element adds depth to Blomkvist’s personal investment in the case. Its inclusion in the remake could have foreshadowed the altered ending more effectively, creating a richer viewing experience.

The endings themselves present further points of comparison. Variations exist across all three versions regarding Blomkvist’s discovery of Martin Vanger as the killer. In the novel, a photograph of Martin wearing the same jacket as the blurry figure in the parade photo provides the key. The Swedish film shifts this to Blomkvist and Lisbeth deducing the victims were Jewish, leading them to Harald Vanger. Blomkvist’s confrontation with Harald, interrupted by Martin, precedes the revelation at Martin’s house. Fincher’s film mirrors the Jewish victim deduction and Harald suspicion, but Blomkvist’s conversation with Harald reveals the crucial jacket detail, leading to the break-in at Martin’s. The Swedish film’s sequence feels slightly more organically developed.

Martin’s demise also differs. The novel depicts Martin intentionally crashing his car into a truck. The Swedish film shows Martin losing control and crashing, with Lisbeth choosing not to save him from the burning wreckage. Fincher’s version similarly involves a crash, but leaking gasoline ignites the car before Lisbeth can intervene.

The Swedish film’s ending stands out for its moral complexity. In the book, Lisbeth’s stated intention to “take” Martin is ambiguous, and her capacity for murder remains untested. Fincher’s film has Lisbeth explicitly ask Blomkvist, “May I kill him?” but the explosion preempts her decision. Only in the Swedish film does Lisbeth actively choose inaction, allowing Martin to burn, a morally gray choice that deepens her character.

Finally, the “twist” regarding Harriet’s fate varies. Both the novel and Swedish film reveal Harriet is alive in Australia. The book uses phone tapping of Anita Vanger, while the Swedish film relies on Lisbeth’s hacking skills. Fincher’s film deviates significantly: Blomkvist deduces that Anita is Harriet, a twist arrived at somewhat arbitrarily. Anita is portrayed as having facilitated Harriet’s escape and then assumed her identity after Anita’s death. This twist feels less earned compared to the foreshadowing present in the Swedish film, where Blomkvist’s earlier confusion between the cousins makes the revelation more plausible in retrospect.

Despite these differences, neither ending definitively surpasses the other. The change feels more cosmetic, not addressing the underlying issues of the religious-killings-turned-generic motive. The religious aspect, initially feeling tacked-on in the book, became more integrated in the Swedish film. However, Fincher’s film arguably lacks clarity on the shift from religious to non-religious killings, potentially confusing viewers unfamiliar with the source material. Understanding audience perspectives solely familiar with Fincher’s version would be insightful.

The post-denouement sequences also warrant comparison. While novels can accommodate extended epilogues, films are less forgiving. Both Swedish and American films have lengthy epilogues, but the American version feels particularly drawn-out. Oplev’s film concisely shows Lisbeth’s Wennerstrom operation via a news report. Fincher’s devotes considerable screen time to a Mission: Impossible-esque sequence, disrupting the film’s pacing so late in the narrative. Such extended sequences might be better suited for bonus content.

Ultimately, no single version emerges as definitively superior. Each adaptation of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo possesses strengths and weaknesses. A hypothetical perfect version might Frankenstein elements from all three, but even then, animating such a creation would be challenging. The core issue might lie in the source material itself. Despite compelling characters and a captivating setting, the central plot is, at its heart, a somewhat generic serial killer narrative. No matter the stylistic dressing, the “locked room” mystery of the sprawling book doesn’t fully translate to film, lacking sufficient red herrings and genuine suspense. The films proceed towards their conclusions with a sense of inevitability rather than genuine mystery.

If forced to choose, a hybrid approach seems ideal: a script akin to the Swedish film (with some adjustments), directed by David Fincher, and starring Rooney Mara. Incorporating specific scenes from Oplev’s film would further enhance this theoretical version. Despite Fincher’s remake being marketed as the darker, grittier adaptation, the Swedish film often surpasses it in visceral impact. The subway attack, for example, is more brutal and raw in Oplev’s film. Lisbeth’s laptop breaks during the assault, not a petty theft attempt. Her subsequent rage is animalistic, brandishing a broken bottle. Even Bjurman’s initial mistreatment feels more intense in the Swedish adaptation. The escalating violence in both versions is undeniably horrific, rendering debates about which rape scene is “more hard-hitting” irrelevant.

Lisbeth Salander remains a complex, untamed character. No single interpretation fully captures her multifaceted nature. She defies easy categorization, impulsive, flawed, and fiercely independent. Perhaps this very complexity is what makes her so compelling, like a tattoo that constantly reveals new details upon closer inspection. The story’s journey continues with The Girl Who Played With Fire, often considered the strongest novel and Swedish film adaptation in the trilogy. Its departure from serial killer tropes and deeper exploration of Lisbeth’s backstory offer richer narrative possibilities. Hopefully, Fincher might revisit this world and deliver another compelling installment, further etching Lisbeth Salander into the cultural consciousness, a character as lasting as a well-crafted tattoo from a truly unforgettable ‘tattoo book’.

Get The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo at Bookshop or Amazon

Get The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo Bluray at Amazon

Get The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo extended trilogy at Amazon