For years, the title of the world’s oldest tattoos was hotly debated amongst tattoo scholars and archaeologists alike. While many believed a mummy from the Chinchorro culture of South America held the prestigious honor with its faint, pencil-thin mustache tattoo, groundbreaking research has definitively settled the score. The true record holder resides with Ötzi, the European Tyrolean Iceman, whose remarkably preserved body, discovered frozen in an Alpine glacier on the Austrian–Italian border, reveals a stunning collection of 61 tattoos dating back to approximately 3250 B.C.

Ötzi’s intricate tattoo patterns, adorning areas such as his left wrist, lower legs, lower back, and torso, offer an unprecedented glimpse into the ancient practice of tattooing over 5,300 years ago. This discovery not only solidifies Ötzi’s place in history but also pushes back the known origins of tattooing, providing invaluable insights into the cultural and therapeutic practices of our distant ancestors.

Bracelet-like tattoo on the Iceman's wrist, showcasing ancient body art.

Bracelet-like tattoo on the Iceman's wrist, showcasing ancient body art.

Previously, the spotlight had been on a Chinchorro mummy unearthed in El Morro, Chile. This mummy, estimated to be around 35–40 years old at the time of death around 4000 B.C., was believed to possess the oldest tattoo – a simple mustache design. However, a recent paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports by a team of researchers, including Lars Krutak from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, has re-evaluated the dating, correcting a crucial error and firmly establishing Ötzi’s tattoos as the oldest known to humankind.

Krutak, reflecting on the findings, admitted his initial surprise, stating, “I was surprised by the findings because in previous publications I brought attention to the tattooed Chinchorro mummy and its early date. To me this mummy was like an underdog versus the all-too-popular Iceman that everyone was writing and talking about. But after reviewing the facts, we were compelled to publish the article as soon as possible to set the record straight and stem the tide of future work compounding the error.” This correction highlights the dynamic nature of archaeological research and the importance of continuous review and refinement of historical records.

Determining Tattoo Age: Radiocarbon Dating Sheds Light

The quest to pinpoint the origins of tattooing is a fascinating journey into human history. While written accounts trace tattooing back to fifth-century B.C. Greece and possibly even earlier in China, tangible evidence is primarily found in art, tattoo tools, and, most significantly, preserved human skin. The latter provides the most direct and compelling archaeological proof of this ancient practice.

Radiocarbon dating, a cornerstone of archaeological science, played a pivotal role in resolving the debate between Ötzi and the Chinchorro mummy. This method measures the decay of carbon-14 in organic materials to estimate their age, allowing scientists to accurately determine the timeframe in which Ötzi and the Chinchorro mummy lived, and consequently, the age of their tattoos.

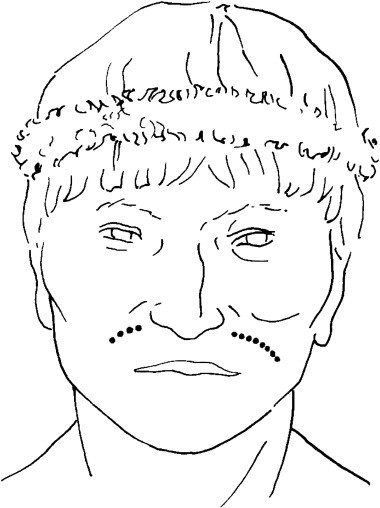

Illustration showing facial tattoos of the Chinchorro mummy, once thought to hold the oldest tattoo record.

Illustration showing facial tattoos of the Chinchorro mummy, once thought to hold the oldest tattoo record.

Ötzi, the Iceman, has been the subject of intense scientific scrutiny for over two decades. His clothing, tools, and even his own tissues have undergone extensive radiocarbon dating, revealing a wealth of information about his life, health, environment, and death. Intriguingly, his tattoos, clustered around areas of joint and spinal degeneration, suggest a potential therapeutic purpose, hinting at early forms of pain management or medicinal tattooing.

In contrast, the Chinchorro mummy remained less studied, prompting researchers to delve deeper into its origins, age, and the nature of its tattoos to accurately place it within the timeline of tattoo history.

The Transcription Error: Unraveling the Chinchorro Mummy’s True Age

The breakthrough in definitively dating Ötzi’s tattoos as older than the Chinchorro mummy’s lies in the meticulous re-examination of radiocarbon dating records. Researchers uncovered a critical error in the transcription of the Chinchorro mummy’s radiocarbon data.

A sample of the Chinchorro mummy’s lung tissue, radiocarbon dated in the 1980s, was initially recorded as 3830 ± 100 B.P. (Before Present). However, the research team posits that a crucial mistake occurred, and this date was erroneously transcribed and subsequently published as 3830 ± 100 B.C. This seemingly small error, repeated in subsequent studies, effectively pushed the Chinchorro mummy’s age back by approximately 4,000 years, incorrectly positioning it as older than Ötzi.

Correcting this transcription error firmly establishes Ötzi as significantly older than the Chinchorro mummy, by at least 500 years, solidifying his tattoos as the oldest known examples of this ancient art form.

Detailed view of tattoos on Ötzi's body, revealing patterns and locations of ancient markings.

Detailed view of tattoos on Ötzi's body, revealing patterns and locations of ancient markings.

While Ötzi currently holds the title of the oldest tattooed human, researchers believe this is unlikely to be the final chapter. His tattoos, indicative of established social and therapeutic practices, suggest that tattooing traditions predate him. Future archaeological discoveries and advancements in dating techniques are anticipated to unearth even older evidence of tattooed mummies, further extending our understanding of the deep history of this enduring art form.

As Krutak aptly concludes, “Apart from the historical implications of our paper, we shouldn’t forget the cultural roles tattoos have played over millennia. Cosmetic tattoos—like those of the Chinchorro mummy—and therapeutic tattoos—like those of the Iceman—have been around for a very long time. This demonstrates to me that the desire to adorn and heal the body with tattoo is a very ancient part of our human past and culture.” The ongoing exploration of ancient mummies worldwide holds the promise of even more exciting discoveries, potentially pushing the origins of tattooing further back into the mists of time, revealing just how deeply ingrained this practice is in the human story.