Maori tattoos, deeply rooted in the culture of the indigenous people of New Zealand, are much more than just skin decoration. Known as Ta Moko, this traditional art form is a profound expression of identity, heritage, and personal narrative. While historically representing tribal affiliations for the Maori people, these intricate designs hold a broader spectrum of meanings for those from different backgrounds who are drawn to their powerful aesthetic and symbolism. These meanings can range from representing family and life journey to prosperity, strength, and personal growth.

Telling Your Story Through Kirituhi: The Art of Maori Tattoo

Historic Ta Moko image

Historic Ta Moko image

While Ta Moko traditionally refers to facial tattoos, the term Kirituhi (Kiri meaning skin, and Tuhi meaning art) is often used to describe Maori-style tattoos applied to other parts of the body, such as the arms and body, making this sacred art form accessible and adaptable. Regardless of the location, the essence of Maori tattoo design lies in its distinctive elements and their symbolic weight.

All Maori tattoo designs are constructed from a set of core design elements, each carrying significant meaning.

The prominent flowing lines within a Maori tattoo are known as Manawa lines. Manawa, the Maori word for heart, symbolizes your life force, your journey through life, and your time on Earth. These lines act as the central framework of the tattoo, representing the individual’s personal story.

Branching off the Manawa lines are Koru patterns. Inspired by the unfurling shoots of the New Zealand fern, Koru embody new life, growth, and beginnings. In tattoo designs, Koru are frequently used to represent individuals and groups of people who are significant in one’s life. Each Koru extending from the Manawa line can symbolize important figures like parents, grandparents, children, siblings, loved ones, friends, and family, weaving a tapestry of relationships into the tattoo.

Deciphering the Infill Patterns: Black Areas and Their Significance

The solid black infill areas within Maori tattoos are not merely decorative; they are integral components with distinct meanings, adding layers of depth and narrative to the artwork.

|  Pakati Infill Pattern for Maori Tattoo |

Pakati Infill Pattern for Maori Tattoo |

Pakati: This infill pattern, resembling a dog skin cloak, symbolizes the qualities of warriors: courage, strength, and resilience in battles and challenges. |

|—|—|

|

Hikuaua: Representing the Taranaki region of New Zealand and the tail of a mackerel, Hikuaua signifies prosperity and abundance. |

|  Unaunahi Infill Pattern for Maori Tattoo |

Unaunahi Infill Pattern for Maori Tattoo |

Unaunahi: Mimicking fish scales, Unaunahi embodies health, plentifulness, and a connection to the resources of the natural world. |

|

Ahu Ahu Mataroa: This pattern denotes talent and achievement, particularly in sports or athleticism, but can also represent overcoming new challenges and striving for success. |

|  Taratarekae Infill Pattern for Maori Tattoo |

Taratarekae Infill Pattern for Maori Tattoo |

Taratarekae: Inspired by the teeth of whales, Taratarekae is another infill that speaks to strength and resilience. |

|

Manaia: The Manaia is a powerful spiritual guardian, believed to possess supernatural abilities. Traditionally depicted as a figure with a bird-like head, human body, and fish tail, it acts as a protector of the sky, earth, and sea. It is seen as a guiding spirit, watching over and directing one’s soul. |

| |

Hei Tiki: Widely recognized as a good luck charm and a symbol of fertility, the Hei Tiki represents clarity of thought, perception, loyalty, and wisdom. Wearers are believed to possess strength of character. Considered a talisman by the Maori people since ancient times, the Hei Tiki is thought to represent the unborn human embryo and is a treasured symbol passed down through generations, often carved from greenstone. |

While Kirituhi extends the art form beyond the face, the deep respect for the tradition and symbolism remains paramount.

The Journey of Crafting Your Maori Tattoo at Zealand Tattoo

Zealand Tattoo emphasizes a collaborative and meaningful process in creating custom Maori tattoos. The journey begins with a consultation, whether in person or online, where clients can share their personal stories and ideas with the artist to develop a unique concept.

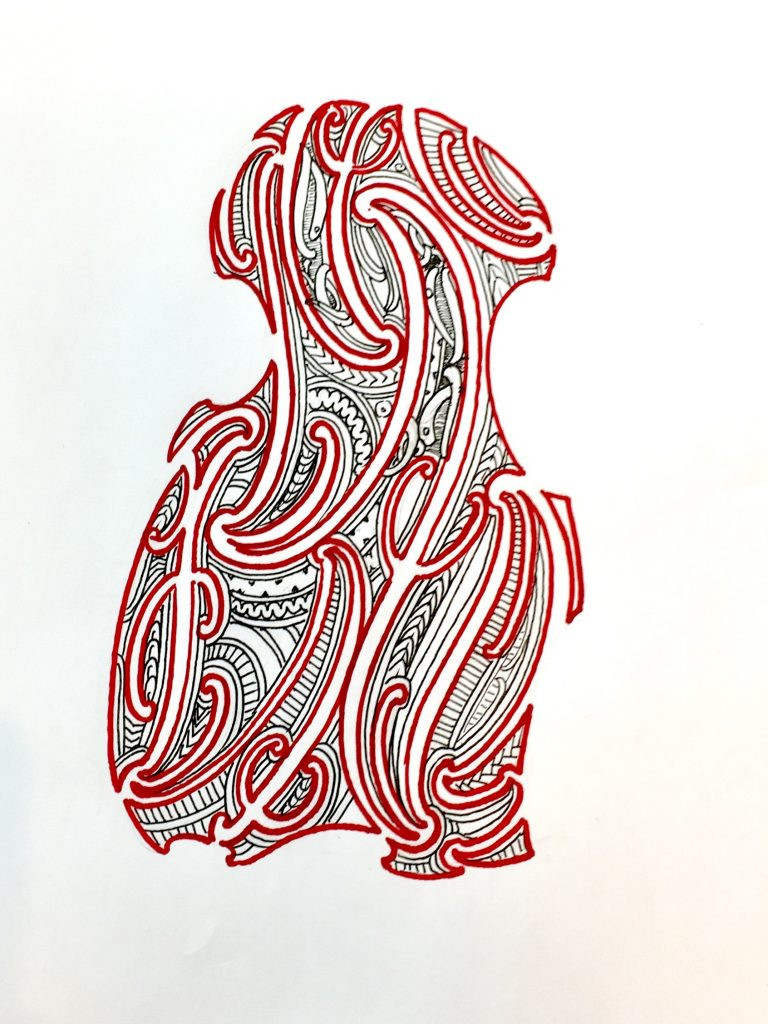

Typically, on the appointment day, a consultation takes place to delve into the specific meanings the client wishes to incorporate into their design. The artist then creates a preliminary sketch, providing a visual representation of the design and how it embodies the client’s intended meanings.

Artist’s Initial Design Draft Reflecting Client’s Story

The Art of Freehand Maori Tattooing

What truly distinguishes Zealand Tattoo’s approach is the freehand application of the design. The artist directly draws the tattoo onto the skin using tattoo marker pens, ensuring that all chosen symbols and representations are integrated authentically within the piece, adhering to traditional Maori symbolism. This freehand technique allows the design to naturally flow and complement the individual contours of the body, creating a truly personalized and organic artwork. Only when the client is completely satisfied with the design’s appearance is the tattoo permanently applied.

Artist Hand-Drawing the Freehand Maori Tattoo Design Directly onto the Skin

Understanding Maori Tattoo Art: Origins and Significance

The Maori people, the tangata whenua (indigenous people) of New Zealand, inherited the art of tattooing from their Polynesian ancestors. This art form, known as moko or Maori tattooing, is considered tapu, or sacred.

Ngapuhi Maori elder with facial tattoo

Ngapuhi Maori elder with facial tattoo

For Maori, the head is the most sacred part of the body, making facial tattoos the most prestigious form of moko. These intricate tattoos, characterized by curved lines and spirals, often covered the entire face and served as powerful indicators of social standing, lineage, power, and prestige. Traditionally, receiving a Maori tattoo was a significant rite of passage, steeped in ritual and reverence, often commencing during adolescence. A defining characteristic of Maori tattoos is their individuality; each design is unique, reflecting the personal story and identity of the wearer. These elaborate and detailed tattoos showcase the exceptional artistry inherent in Maori culture and the skill of the tohunga ta moko, the Maori tattoo artist or moko specialist. Tohunga ta moko held a highly respected position in society, considered tapu themselves. While predominantly men, some women also practiced this sacred art.

The Journey of Maori Tattoo Art to Global Recognition

The introduction of Maori tattooing to the Western world can be traced back to Captain James Cook’s voyages in 1769. The very word “tattoo” is believed to be derived from Cook’s adaptation of the Tahitian word “tatau.” Cook and his crew, including Joseph Banks, were captivated by the elaborate tattoos they witnessed on Maori tribesmen during their explorations of the South Pacific. European explorers in New Zealand developed a strong fascination with Maori tattooing and culture.

Historically, tattooed heads of enemies were taken as trophies in warfare, symbolizing power and protection. Contact between Maori and Europeans led to a dark chapter in this history. Missionaries arrived in the early 19th century, seeking to convert the Maori to Christianity. In 1814, a Maori chief named Hongi traveled to England with missionaries. There, he collaborated with an Oxford professor on a Maori dictionary and Bible translation. Presented to King George IV and gifted generously for his efforts, Hongi exchanged these gifts for muskets and ammunition in Sydney on his return journey. These weapons were then used in raids against rival tribes.

Tragically, a gruesome trade emerged where Europeans exchanged weapons for tattooed Maori heads. This demand led to raids solely for the purpose of acquiring tattooed heads for trade. Traders sold these heads to museums and private collectors in Europe. In a desperate attempt to meet the demand for weapons, Maori even resorted to beheading slaves and commoners captured in battle, tattooing their heads posthumously, and trading even poorly tattooed or unfinished heads. Major General Horatio Robley became a notorious collector, amassing around 35 tattooed heads, a significant portion of which are now housed in the Natural History Museum of New York. Robley also authored a book titled “Moko,” documenting the process and meaning of Maori tattoo designs, further disseminating knowledge, albeit sometimes through a colonial lens.

The Intricacy of Maori Tattoo Techniques

Traditional Maori tattooing methods differed significantly from modern needle-based techniques. Instead of needles, Maori tohunga ta moko employed uhi, which were sets of chisels and knives crafted from materials like shark teeth, sharpened bone, or stone. Albatross bone was a prized material for uhi, although iron was also sometimes used. These tools, either smooth or serrated, were used interchangeably to create the desired patterns and textures on the skin.

The pigments used in Maori tattoos were derived entirely from natural sources. Black pigment, reserved for facial tattoos, was made from burnt wood. Lighter pigments, used for outlines and less sacred tattoos, were created from caterpillars infected with a specific fungus or from burnt kauri gum mixed with animal fat. These precious pigments were stored in ornate containers called oko, which became family heirlooms, often buried when not in use to protect their tapu nature.

Before commencing the tattooing process, the tohunga ta moko would carefully study the individual’s facial structure to determine the most fitting and aesthetically pleasing design, underscoring the personalized nature of each moko.

The Painful Rite of Passage

Receiving a traditional Maori tattoo was an intensely painful experience. Deep cuts were made into the skin using the uhi. The chisel was then dipped in pigment and tapped into the cuts, or alternatively, pigment was applied to the skin, and the chisel dipped in water was used to drive the pigment into the skin. This method resulted in grooved skin after healing, unlike the smooth surface left by needle tattoos. Due to the pain and labor-intensive nature of the process, tattooing was done in stages, allowing for healing between sessions.

Two primary design styles existed: one where only the lines were blackened, and another, known as puhoro, where the background was blackened, leaving the lines clear, creating a striking contrast.

The Sacred Protocols Surrounding Maori Tattooing

The sacredness of Maori tattoo extended to strict protocols during the tattooing process. Individuals undergoing tattooing, along with those involved in the practice, adhered to specific restrictions. They were forbidden from eating with their hands or engaging in conversation with anyone outside of those directly involved in the tattooing. It was crucial for those receiving tattoos to suppress any outward signs of pain, as crying out was considered a sign of weakness. Enduring the pain with stoicism was a matter of pride.

Further regulations, particularly for facial tattoos, included abstaining from sexual intimacy and solid food. To maintain nourishment without contaminating the swollen and open skin, individuals were fed liquids through a wooden funnel until the facial wounds healed completely. Karaka tree leaves were applied as a soothing balm to promote healing after each session. Music, singing, and chanting often accompanied the tattooing process, serving to alleviate pain and create a ritualistic atmosphere.

Facial Focus and Gender Distinctions

The face held central importance in Maori tattooing. Men traditionally received full facial moko, while women’s tattoos, known as moko kauae, were typically concentrated on the chin, lips, and nostrils. While facial tattoos were paramount, other body parts, such as the back, buttocks, and legs, were also tattooed, particularly for men. Women were more commonly tattooed on the arms, neck, and thighs.

Maori Tattoo and Social Hierarchy

Access to Maori tattoos was dictated by social standing and means. Only individuals of rank or status could receive and afford moko. Slaves, for instance, were prohibited from having facial tattoos. Conversely, those who possessed the means to acquire moko but chose not to were perceived as being of lower social status.

Beyond signifying rank, facial moko served as a form of identification, a visual record of a man’s lineage, accomplishments, status, position, ancestry, and marital status. It was considered deeply disrespectful to be unable to recognize a person’s mana (prestige and authority) and position through their moko.

The male facial moko was meticulously structured, divided into eight key sections, each conveying specific information:

- Ngakaipikirau (center forehead): Indicated general rank.

- Ngunga (under brows): Designated position.

- Uirere (eyes and nose area): Revealed hapu (sub-tribe) rank.

- Uma (temples): Detailed marital status, including the number of marriages.

- Raurau (under nose): Displayed a man’s signature, memorized by chiefs for official purposes.

- Taiohou (cheek area): Showed the nature of his work.

- Wairua (chin area): Indicated mana or prestige.

- Taitoto (jaw area): Designated birth status.

Ancestry was also visually represented on each side of the face, with the left side typically representing the father’s lineage and the right side the mother’s. Noble or significant ancestry was a prerequisite for receiving moko. If one side of a person’s lineage lacked rank, that corresponding side of the face might remain untattooed. Similarly, individuals without rank or notable lineage would have the center of their forehead left without design.

Maori Tattoo as a Resurgent Art Form

By the mid-19th century, the practice of full facial moko for men began to decline, while moko kauae for women persisted throughout the 20th century. However, since the 1990s, Maori tattooing has witnessed a powerful resurgence, often utilizing modern tattoo machines. The global rise in popularity of tribal tattoo patterns in the late 1990s and early 2000s led to non-Maori individuals adopting and adapting Maori designs. This, in turn, has fueled a renewed interest in more traditional Maori art forms, with people increasingly seeking to incorporate their own personal meanings and narratives within the framework of traditional designs. While modern techniques are often employed, the underlying respect for the cultural significance of Maori tattoo remains vital.

Maori Tattooing and Tradition Endure

The Maori people are actively revitalizing traditional tattooing methods as a crucial aspect of preserving their cultural heritage. Both men and women are now participating in this resurgence of traditional practice. Organizations like Te Uhi a Mataora, established by traditional Maori tattoo practitioners, are at the forefront of this movement. Te Uhi a Mataora is dedicated to safeguarding and furthering the development of ta moko as a living art form. A key concern for this organization is the increasing appropriation of ta moko by non-Maori individuals without proper understanding or respect for its cultural context. They are committed to promoting the art form through the revival of traditional techniques and designs, and educating the wider public about the profound cultural significance of Maori tattooing, emphasizing that it should not be treated lightly or appropriated without cultural sensitivity.

For non-Maori individuals who admire Maori artwork and are considering getting a tattoo, it is strongly advised to seek out Maori tattoo artists who possess deep knowledge of ta moko and Kirituhi. At Zealand Tattoo, experienced Maori artists are dedicated to creating custom, yet respectful and authentic, Maori designs that honor the tradition.

Exploring Maori Designs and Their Meanings

Te Ora O Maui (The Story of Maui) Design

This design tells the legend of Maui, the youngest of five brothers. Born prematurely, his mother believed him stillborn and cast him into the sea wrapped in her topknot. Maui was rescued and raised by a tohunga, who taught him essential skills and knowledge, including navigation and shapeshifting. Maui became renowned for his exceptional abilities, particularly in navigation, and accomplished legendary feats such as slowing the sun, obtaining fire from Mahuika, the fire goddess, and attempting to gain immortality for humankind from Hine-nui-te-po, the goddess of the night and death. This Maori design symbolizes Maui fishing up or discovering Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Pikorua (Twist) Design

Pikorua, the Maori word for “twist,” represents the intertwining and joining of two separate entities, such as earth and sea, or people and cultures. Some iwi (tribes) believe it symbolizes the primordial union of Ranginui (sky father) and Papatūānuku (earth mother). The design embodies the Maori belief in interconnectedness and the cyclical nature of life, where all paths, like rivers flowing to the ocean, eventually converge. Pikorua represents life’s journey, the diverse paths we take, and our shared destination.

Nga Hau E Wha (The Four Winds) Design

This design symbolizes the four corners of the earth and the four winds (nga hau e wha). It acknowledges the power of Maori gods or Atua like Tāwhirimātea (god of storms) and Tangaroa (god of the sea) to both create and destroy. Regardless of personal beliefs, the design emphasizes respect for the forces of nature and the gifts bestowed upon humanity. It represents Aotearoa as a land embracing people of all backgrounds and beliefs. Elements within the design often include Tamanuitera (sun god, representing new growth and warmth), Hei Matua (representing strength and prosperity), and koru (symbolizing continuation and harmony).

Te Timatanga (The Beginning) Design

Te Timatanga depicts the Maori creation story of Ranginui (sky father) and Papatūānuku (earth mother), who were initially locked in a tight embrace, plunging the world into darkness. Their children, yearning for light and space, decided to separate their parents. Tūmatauenga (god of war) first attempted to separate them but failed. Finally, Tānemahuta (god of forests and birds) successfully pushed them apart, bringing light into the world and allowing life to flourish. Tāwhirimātea (god of storms), opposed to the separation, retreated to the sky with his father and periodically unleashes storms upon his brothers in anger. Ruaumoko (god of earthquakes), still in his mother’s womb, also punishes Tāne with earthquakes from time to time. This design commemorates the creation and the ongoing forces shaping the world.

Common Stand-Alone Maori Designs

| |

Koru (Spiral): Drawing inspiration from the unfurling fern frond, the Koru symbolizes new beginnings, growth, harmony, and spiritual rebirth. New Zealand’s ferns are renowned for their beauty and unique forms, making the Koru a powerful and evocative symbol. |

|—|—|

|

Hei Matau (Fish Hook): The Hei Matau, or fish hook, is a prominent Maori symbol of prosperity and abundance. Fish were a vital food source for Maori, and owning a fish hook signified sustenance and wealth. Beyond prosperity, it also represents strength, determination, good health, and safe journeys over water. |

| |

Single Twist (Pikorua): The single twist symbolizes the path of life and eternity. Distinct from double and triple twists, the single twist represents an individual life journey. |

|

Double or Triple Twist (Pikorua): These interconnected twists represent the bond between two people, cultures, or spirits. They symbolize eternal connection, even amidst life’s challenges, signifying enduring friendship, loyalty, and love. This design is a cherished Maori symbol of lasting relationships. |

For a striking and deeply personal piece of art that reflects your individual story while honoring the rich traditions of Maori culture, consider a custom-designed Maori tattoo crafted with the highest standards of artistry and cultural respect.