Tattoos in mainstream society are increasingly common, often seen as a form of self-expression and personal art. While getting inked at a professional studio is a well-considered decision for many, the world of tattoos takes on a different dimension behind prison walls. Forget sterile environments and regulated inks; in jail, tattoos are created using rudimentary tools and methods born out of necessity and resourcefulness. This article delves into the clandestine culture of Jail Tattoos, exploring their significance as a coping mechanism, a symbol of identity, and a permanent record of life inside.

To truly understand the reality of jailhouse ink, we journeyed into several prisons in Romania. Through conversations with inmates, we uncovered the intricate processes, the profound meanings, and the complex emotions etched onto their skin. We learned about the evolution of techniques from dangerous, infection-prone methods to slightly more advanced improvisations, the symbolic bartering system involved, and the ever-present question of regret.

The Culture of Ink: More Than Skin Deep in Prison

For inmates, tattoos are far more than mere body decoration. They become a crucial part of navigating the harsh realities of prison life. In an environment designed to strip away individuality, tattoos serve as a powerful means of reclaiming personal identity and expressing inner feelings. In a world where control is limited, marking one’s own body becomes an act of self-determination. These tattoos can represent a connection to the outside world, a reminder of loved ones, or a badge of survival within the prison system itself. They become visual narratives of personal stories, etched in ink and carried for life.

From Boot Heels to Batteries: The Evolution of Tattooing Methods

The techniques used to create jail tattoos are a testament to inmate ingenuity, born from limited resources and a desire for self-expression. Marius, a 35-year-old inmate at Jilava Prison, recounts the stark contrast between past and present methods. In the 1990s, the ink itself was a dangerous concoction.

Alt text: Close-up of inmate Marius’s chest tattoos, displaying names inked as personal memorials.

“We’d make the ink out of the heels of the warden’s boots,” Marius explains, detailing a process that sounds more akin to survival tactics than art. Working as a shoeshiner in a juvenile detention center, he and others would scrape off tiny fragments of boot heels, meticulously hiding their actions to avoid detection. These scrapings were then burned under glass and dissolved in urine, transforming into a crude, makeshift ink. The application was equally primitive and perilous. A sewing needle, wrapped with thread from towels, served as the tattooing tool, with images etched by tearing the skin. Infections were rampant, an ever-present danger in this unsanitary practice. “After a while, your skin couldn’t take it anymore,” Marius recalls, highlighting the physical toll, yet the social pressure to participate was immense: “But I kept doing it because everybody else was.”

Today, while still far from hygienic studio conditions, methods have evolved. The modern jail tattoo machine is an improvised device, typically constructed using the motor from an electric toothbrush and the spring from a pen. This rudimentary tool, while still carrying significant risks, represents a step away from the more archaic and brutally unsafe methods of the past.

Alt text: Jail inmate Marius displaying an arm tattoo featuring the name “Claudiu,” showcasing personal ink.

Personal Ink: Stories Etched in Confinement

Marius’s tattoos are deeply personal narratives. The names inked across his chest – Claudiu, Larisa, and Ady – represent his nephew, daughter, and late brother, respectively. “I wanted their names close to my heart,” he shares, explaining that these tattoos were etched during a period of intense struggle with imprisonment, serving as anchors to his life outside. Each of his eight tattoos tells a story of connection and relationship, becoming permanent reminders of the bonds that sustain him.

In 2010, while incarcerated, Marius got “Elena” tattooed on his shoulder, a testament to a relationship formed over phone calls with a woman while he was still married. In a dramatic display of commitment, they got tattoos of each other’s names simultaneously, despite their physical separation.

Alt text: Tattoo cover-up on Marius’s shoulder, “Blondie,” illustrating personal relationship changes and ink modifications in prison.

However, his wife, already facing restricted visitation rights for attempting to smuggle in a phone charger, was far from pleased with this new addition. Her discovery led to Marius covering “Elena” with “Blondie,” his pet name for his wife, a visible attempt at reconciliation etched in ink.

Mădălina, a 28-year-old inmate at the Ploiești – Târgșorul Nou Women’s Prison, waited until she was 24 to get her single tattoo, a design chosen from catalogues. Pregnancy had initially delayed her plans.

Mădălina's butterfly and flower leg tattoo

Mădălina's butterfly and flower leg tattoo

Her tattoo, featuring butterflies and flowers, embodies a different sentiment. “For me, the flower the butterflies represent how delicate life can be,” she reflects, finding solace in the imagery of fragility and beauty amidst confinement.

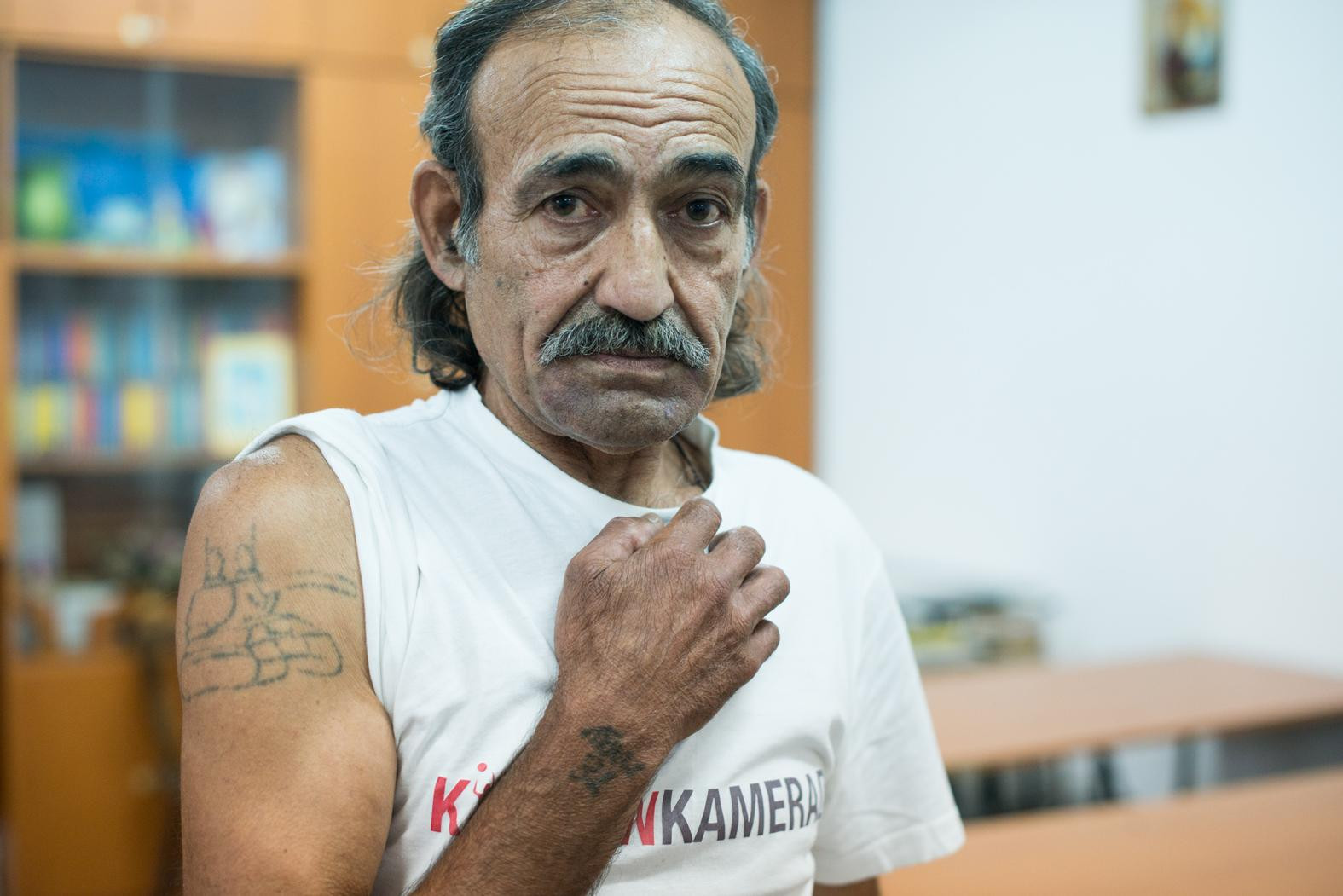

Corneliu, 62, at Ploiești Prison, received his first tattoo at 14, a boxing glove, fueled by youthful bravado and the pressure from an older brother. A passionate boxer then, he hoped for a professional career.

Corneliu showing his boxing glove tattoo

Corneliu showing his boxing glove tattoo

Using just needles and ink at home, he etched the image himself, an act intended to prove his courage. “I did it to prove I was brave, which is the same reason many prisoners get tattoos in jail,” he states, drawing a direct line between youthful impulsiveness and the motivations behind jailhouse ink. His parents’ anger underscored the permanent nature of his teenage decision.

Corneliu's first tattoo close-up

Corneliu's first tattoo close-up

Later, his aspirations shifted from boxing to woodcutting. Inspired by his new path, he tattooed a fir tree, envisioning it as “one tree ‘that nobody could chop down.'” However, while in jail in 1992, the tree was covered with a crown. “It’s easy to get a tattoo behind bars,” he observes with a hint of irony, “All you need is a needle, ink, and some courage.” Today, Corneliu regrets them all, expressing a desire to erase these permanent marks: “If I could, I’d cut them all out with a blade.”

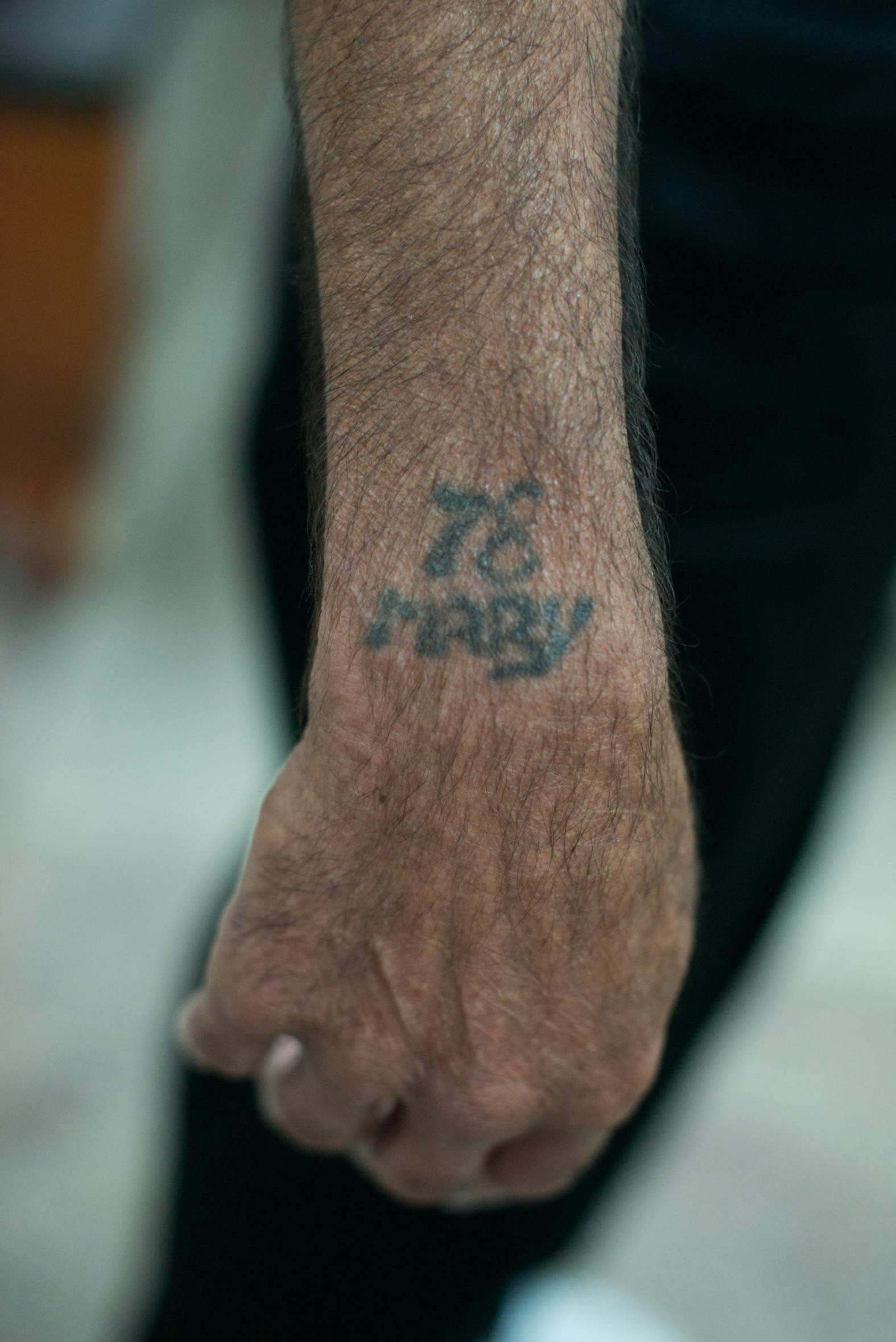

Vaile, 60, also at Ploiești Prison, got his first tattoo in 1978 after army conscription. He chose his girlfriend Marianna’s name for his chest, believing “if you wear the name of a loved one on your skin, then they’re always close by.”

Vaile showing his chest and hand tattoos

Vaile showing his chest and hand tattoos

Their relationship ended, creating an awkward situation with his next girlfriend who discovered Marianna’s name etched on his skin. “I had to lie and tell her that Marianna was dead,” Vaile confesses, highlighting the complications of impulsive, permanent decisions.

Vaile's hand tattoo showing "1978"

Vaile's hand tattoo showing "1978"

Like Corneliu, Vaile now wishes to remove his tattoos, but for a different reason: identification. “If you get in trouble, the police can identify you by your ink,” he points out. “They don’t need to use any fancy forensics, just the images on your body. If they get you, there’s no way you can deny it.” The permanence that once offered connection now represents potential incrimination.

Cristian, 30, also at Ploiești Prison, has so many tattoos he struggles to count them. His first was “on the outside,” but most were done in jail. “It’s a lifestyle for me, something I enjoy,” he states, reflecting a different perspective – tattoo culture as an integral part of his identity, particularly within prison.

Cristian showing his arm tattoos

Cristian showing his arm tattoos

His favorite is a portrait of his grandmother, his primary caregiver. This large tattoo, created using a CD player battery, spoon handle, needle, and ink, is a poignant reminder of family and love amidst the harsh prison environment.

Cristian's grandmother portrait tattoo

Cristian's grandmother portrait tattoo

For Iulian, 28, at Ploiești Prison, tattoos are both “a lifestyle and a list of the people he’s loved.” His first tattoo marked his initial imprisonment. “I was just a kid and wanted to seem tougher than I was, so I could survive this environment,” he admits, highlighting the performative aspect of jail tattoos, especially for younger inmates seeking to establish themselves.

Iulian showing his arm tattoos

Iulian showing his arm tattoos

He plans to get his jail tattoos redone upon release, seeking refinement and visibility. While he favors black tattoos, prison limitations restrict artistic complexity. “All you can do is be careful,” he says, emphasizing hygiene. Iulian avoids infections by assembling his own tattoo machines and never sharing needles, a pragmatic approach to harm reduction within the constraints of prison tattooing.

Sofica, 21, at the women’s prison, has 12 tattoos, mostly names of loved ones. She started at 15, with most done in prison.

Sofica's arm tattoos

Sofica's arm tattoos

However, she now regrets them and considers removal post-release. She notes that extensive tattoos are less common among women in her community, though her mother also has some, suggesting a complex interplay of personal choice and social norms.

George, 34, at Jilava Prison, has numerous tattoos, none from prison. He views jail tattooing as unhygienic and unartistic. In 2010, he covered a previous tattoo with Maori symbols.

George's Maori symbol tattoo

George's Maori symbol tattoo

A rugby player tattoo commemorates his sporting past.

George's family and pigeon tattoos

George's family and pigeon tattoos

In 2013, he added his newborn son’s portrait with birth details, followed by a pigeon hovering over portraits of his wife, mother, grandmother, and father. “It represents the peace and calm I want for all of them,” he explains, showcasing tattoos as expressions of familial love and protective wishes.

Bogdan, 32, at Jilava Prison, received his first tattoo at age 9 from an older friend, using a pen-based machine.

Bogdan showing his chest and arm tattoos

Bogdan showing his chest and arm tattoos

“I was kind of alone, my mum had died, my dad was in jail, I didn’t know what I was doing,” Bogdan recounts, revealing a childhood marked by loss and instability, with tattoos perhaps serving as a form of self-soothing or seeking belonging. He later got tattoos of his wife’s face, daughters’ names, and God. None were done in prison, but his tattoo artist was a former inmate who learned the craft inside, highlighting the ripple effects of prison culture on the outside world. Despite their personal significance, Bogdan would remove them if he could, as “they remind me of the past,” indicating a desire to distance himself from earlier life stages.

The Weight of Ink: Regret and Lasting Marks

The stories of these inmates reveal a recurring theme: regret. While tattoos in prison serve immediate purposes – coping, identity, connection – the long-term consequences are often reconsidered. The crude methods carry health risks, and the impulsive nature of some jail tattoos contrasts with the evolving lives of inmates. For some, like Corneliu and Vaile, regret stems from a desire to erase past decisions or avoid identification. For others, like Sofica and Bogdan, it’s about moving forward from a life chapter they wish to leave behind. Whether symbols of survival, love, or mistakes, jail tattoos remain indelible marks, prompting reflection on choices made in confinement and their lasting impact on life beyond bars.

While tattoo removal is an option, its accessibility within prison systems is limited, and the process itself can be lengthy and costly even outside. Therefore, the stories of jail tattoos serve as a powerful reminder of the complex interplay between personal expression, circumstance, and the enduring nature of ink under the skin.