India boasts a captivating and extensive history of tattoo traditions, stretching across the diverse landscapes of the nation. From the northeastern mountains of Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland to the western deserts of Gujarat, tattoos in India have served purposes far beyond mere aesthetics. They are deeply embedded in cultural practices, acting as markers of identity, spirituality, and even pathways to the afterlife. These intricate forms of body art, often referred to as “Indian Tattoos Tribal,” represent a profound connection to heritage and community.

Despite the immense richness of Indian tattooing traditions, comprehensive documentation remains surprisingly limited. Much of the existing literature is confined to academic reports, governmental records, and aging census documents hidden in archives. Contemporary ethnographic studies are also relatively scarce, partly because many tattooed tribal communities resided in remote areas and faced suppression for maintaining these “primitive” practices. As modernization advanced, tribal tattoos were sometimes viewed as inferior compared to urban lifestyles, leading to a decline in the practice in some areas.

However, through diligent research of historical sources and firsthand accounts from Naga informants, we can piece together a significant overview of traditional tattooing in India, both past and present. This exploration aims to highlight the enduring legacy of “indian tattoos tribal” art and its profound cultural significance.

Ancient Roots of Indian Tattoos

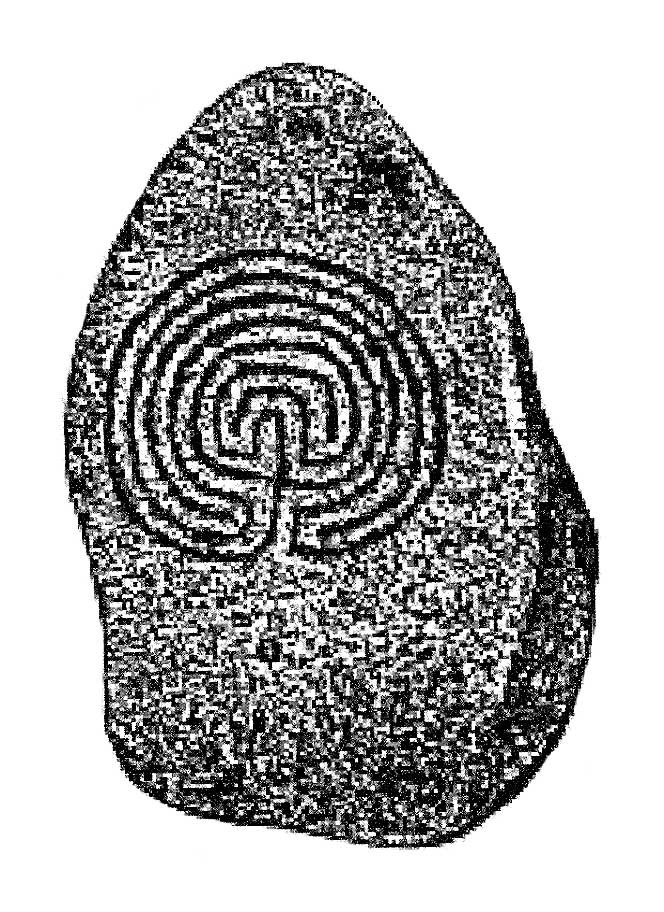

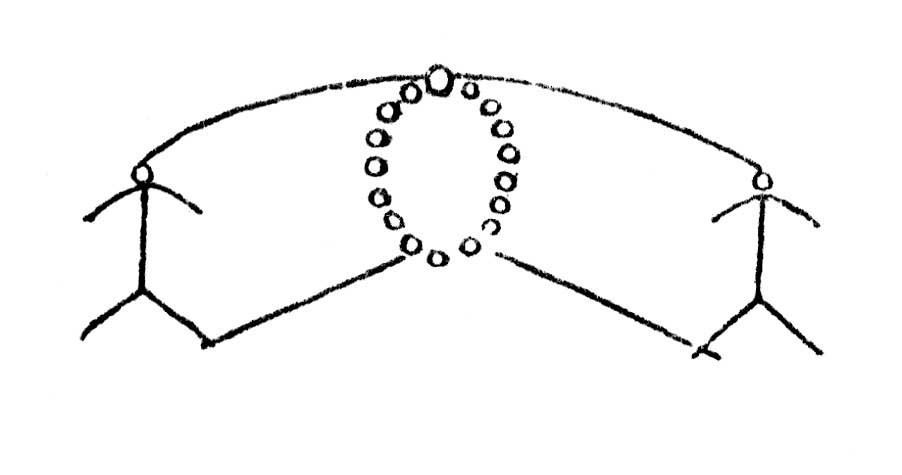

The antiquity of tattoo, known as godna in Hindi, in India is undeniable, though pinpointing its exact origins remains challenging. One compelling clue to its age lies in the striking resemblance between labyrinth designs found in ancient petroglyphs and similar patterns in traditional tattoos. For instance, a rock art site in Goa, dated around 2500 B.C., and a labyrinth inscribed on a dolmen shrine in the Nilgiri Hills from 1000 B.C., display configurations remarkably similar to tattoo motifs.

2500-year-old labyrinth rock carving in Goa

2500-year-old labyrinth rock carving in Goa

Nilgiri Hills labyrinth from 1000 BC

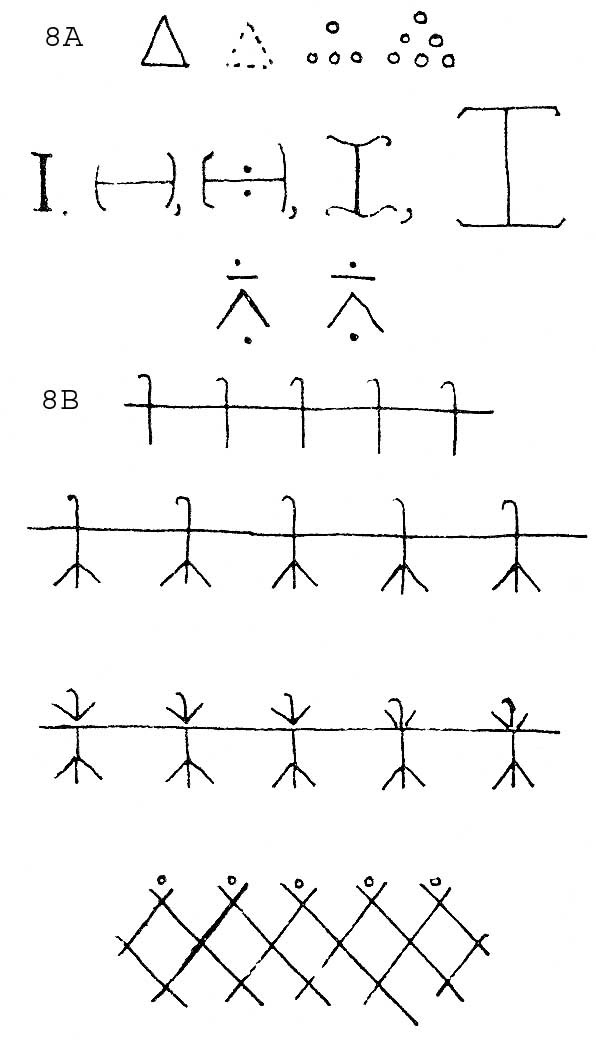

Nilgiri Hills labyrinth from 1000 BC

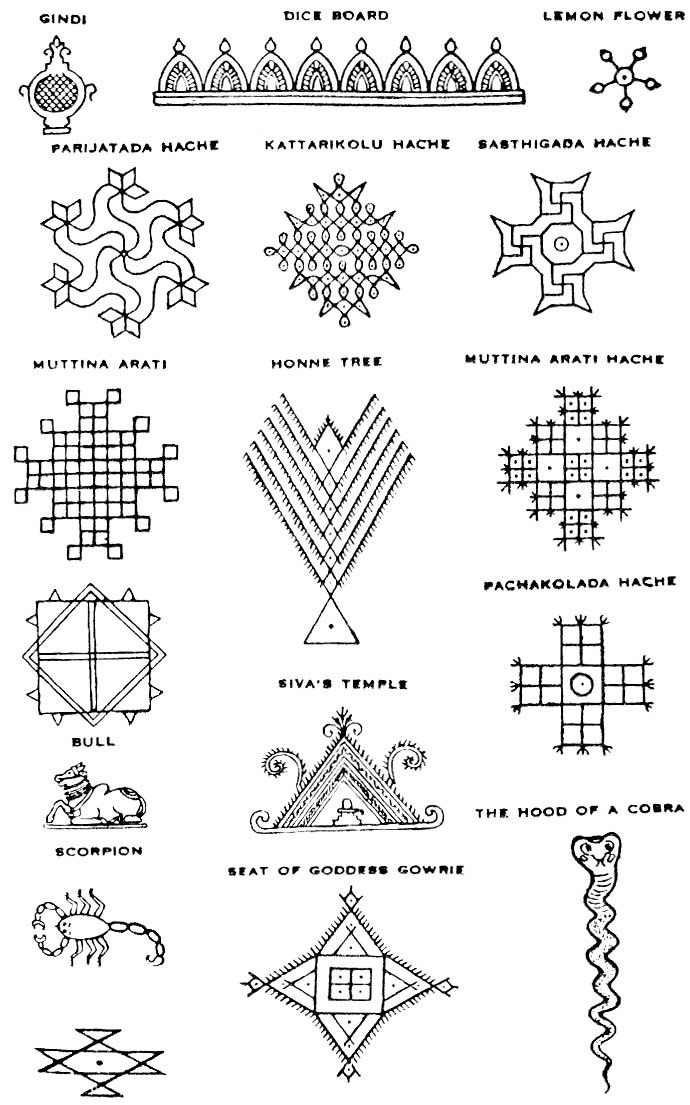

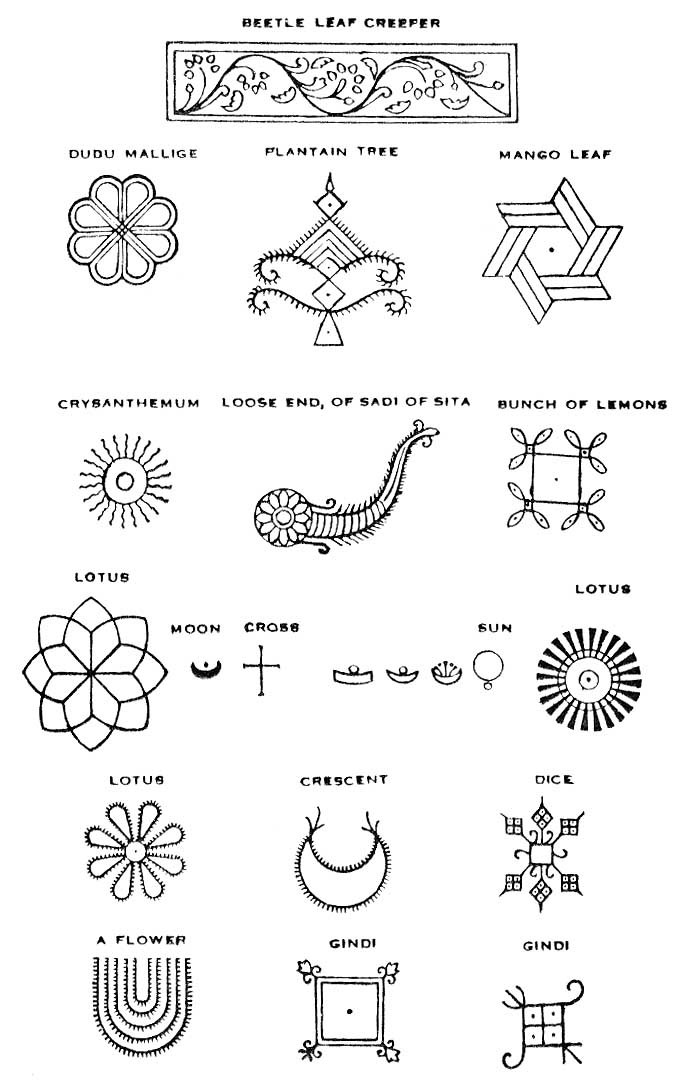

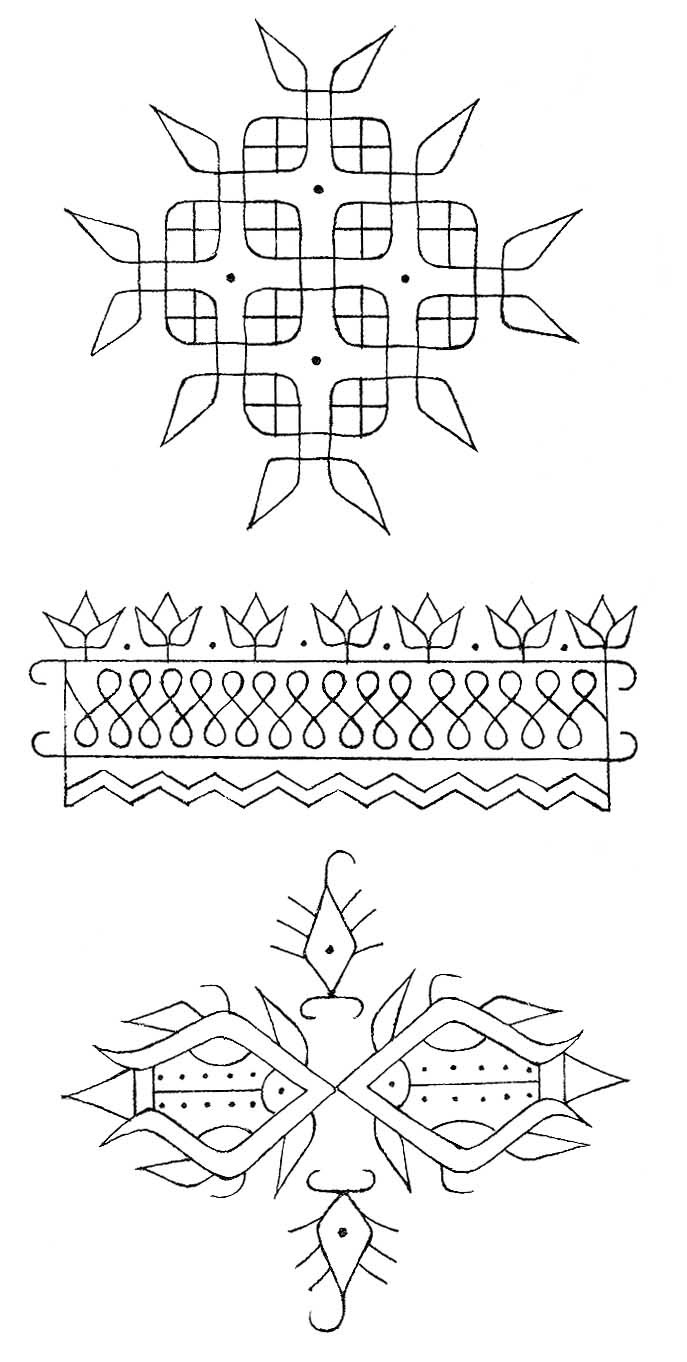

In South India, these labyrinthine patterns find a parallel in magical designs called kolam (Figs. 3 & 4). Kolam are traditionally created by women using lime or rice powder at dawn to invoke protection and prosperity. They are linked to the cobra deity (naga) for fertility and protection, and are believed to ward off evil spirits. The intricate, symmetrical nature of kolam, often drawn as a continuous line forming a complex maze, mirrors the spiritual and protective qualities associated with “indian tattoos tribal” art.

Drawing a Kolam design

Drawing a Kolam design

Kolam tattoo design from circa 1920

Kolam tattoo design from circa 1920

Common Tattoo Designs and Their Meanings

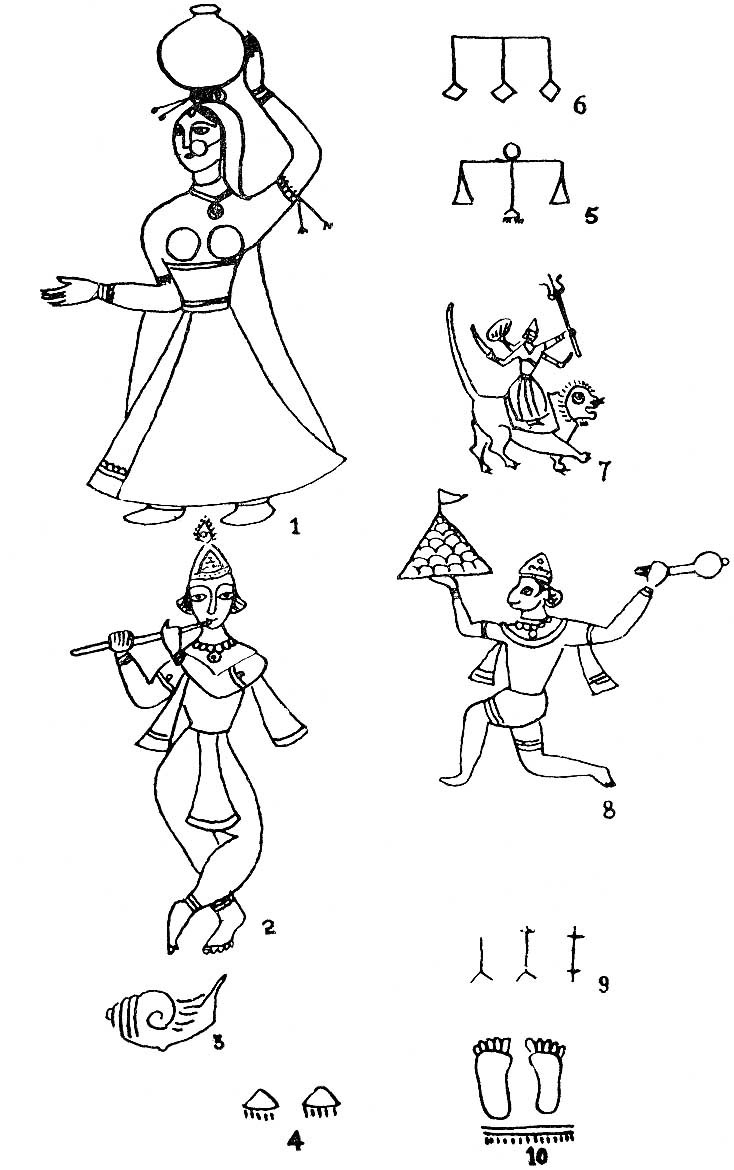

Across India, tattoos are deeply intertwined with magical beliefs and symbolism. A 1902 article detailed the significance of various female tattoo designs, highlighting the protective and symbolic nature of these markings. For example, a simple black dot tattooed on the forehead or chin was believed to ward off the Evil Eye. This “mole” or tattooed dot also represented Chandani, associated with Venus, symbolizing love and union.

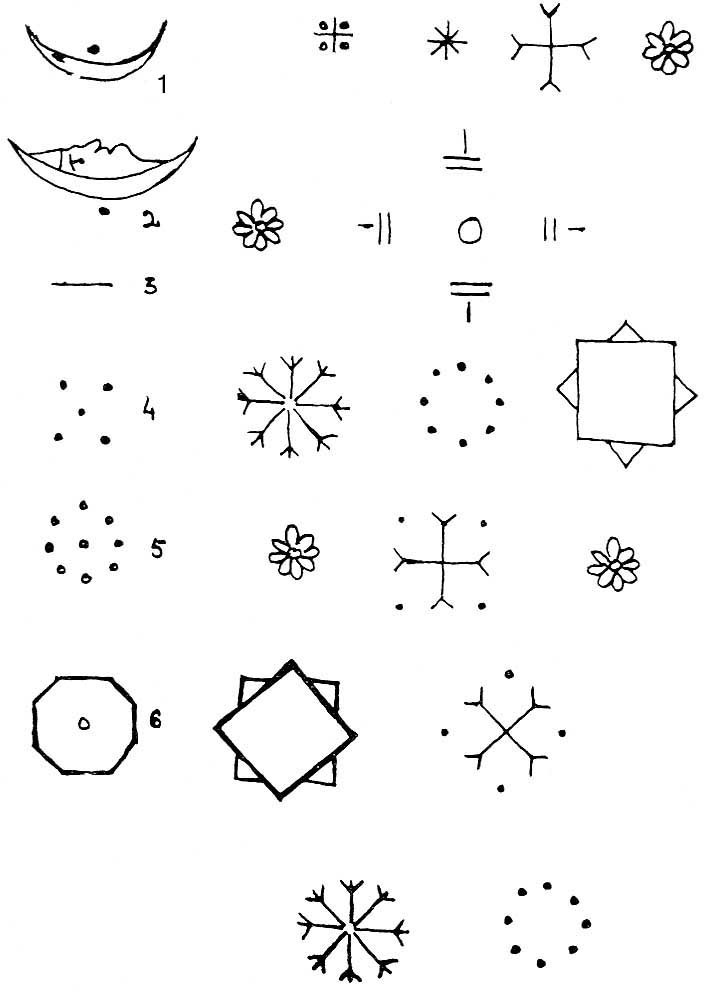

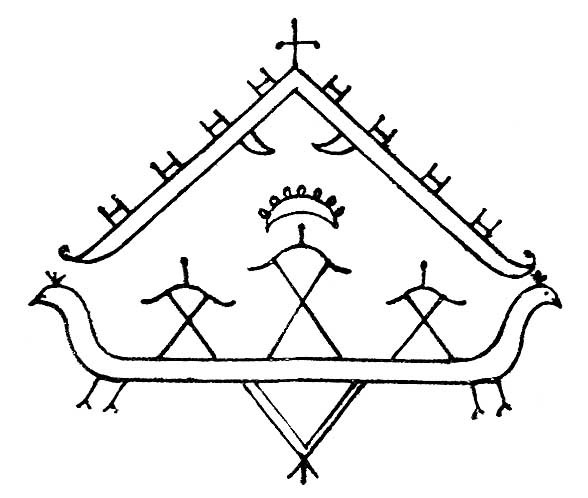

Figs. 1-6. Various Indian tattoo designs with symbolic meanings

Figs. 1-6. Various Indian tattoo designs with symbolic meanings

Other common designs and their symbolic meanings included:

- Line between eyebrows: Represented angara or vibhuti, sacred ash applied for protection against evils.

- Panch Pandavas: Four dots in a square with a central dot, symbolizing domestic harmony among brothers.

- Nine Planets (Grahs): Eight dots in a circle with a central dot, acting as a charm against negative planetary influences.

- Lotus (Phul): An eight-sided figure with a central circle, representing Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, and the universe itself.

- Triangle: Mystic symbol of the female power yoni.

- Fish: Originally represented the female power yoni and considered a symbol of luck.

Tattoos as Caste Markers

Historically, tattoos in India served as indicators of profession and caste. Certain tattoo marks identified individuals within specific communities. For instance, nomadic women of spinning castes were tattooed with the ateran or uteran (spindle) symbol. Milkmaids of Krishna were recognized by specific emblems depicting their caste.

Spinner and milkmaid caste marks in Indian tattoos

Spinner and milkmaid caste marks in Indian tattoos

The Kanhayya’s mukat or “Krishna’s Crown” tattoo was unmistakably associated with Rajput women. Camels as symbols were linked to Banjara women, traders of copper and brass, and the Rabari of Gujarat, nomadic traders known for camel imagery in their tattoos. These “indian tattoos tribal” designs acted as visible markers of social identity and occupation.

Tattoos of heaven and earth symbolism

Tattoos of heaven and earth symbolism

Krishna's Crown tattoo design

Krishna's Crown tattoo design

Figurative and Protective Tattoos

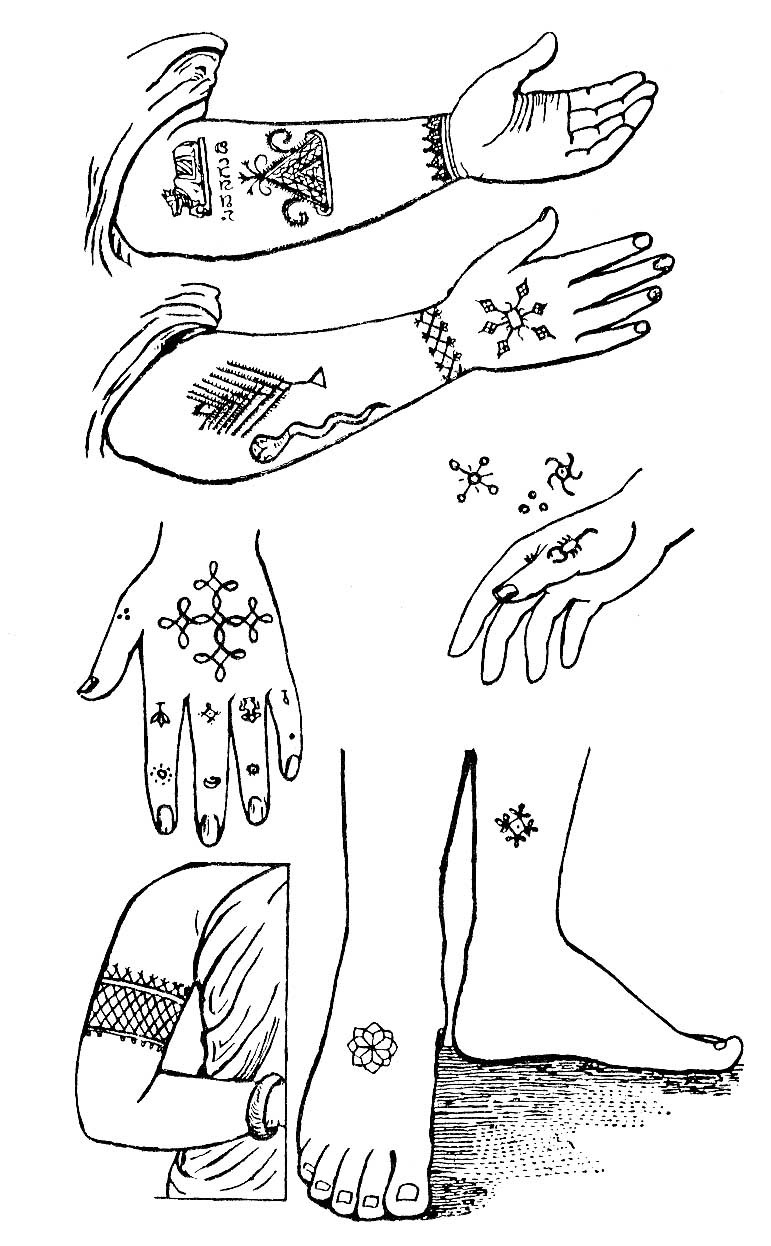

Beyond caste, many “indian tattoos tribal” designs were figurative, representing luck, protection, or medicinal properties. The lotus, peacock, fish, triangle, and swastika were considered auspicious symbols, especially when tattooed on the left arm. The chakra (wheel), stars, pauchi, and “Sita’s kitchen” were protective charms.

Figurative tattoos with protective symbolism

Figurative tattoos with protective symbolism

Tattooing images of scorpions, cobras, bees, or spiders was rooted in sympathetic magic, believed to offer protection from these creatures. The parrot was a love symbol and charm, while the spider was associated with curing leprosy. Various communities across India believed in the medicinal properties of tattoos, with some groups believing they maintained organ health or promoted safe childbirth.

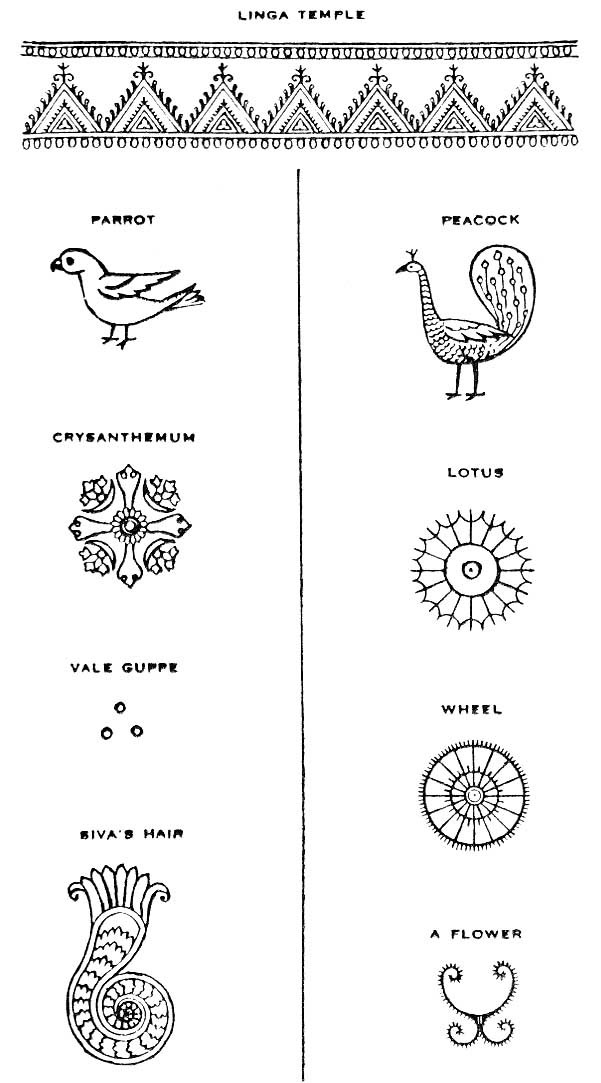

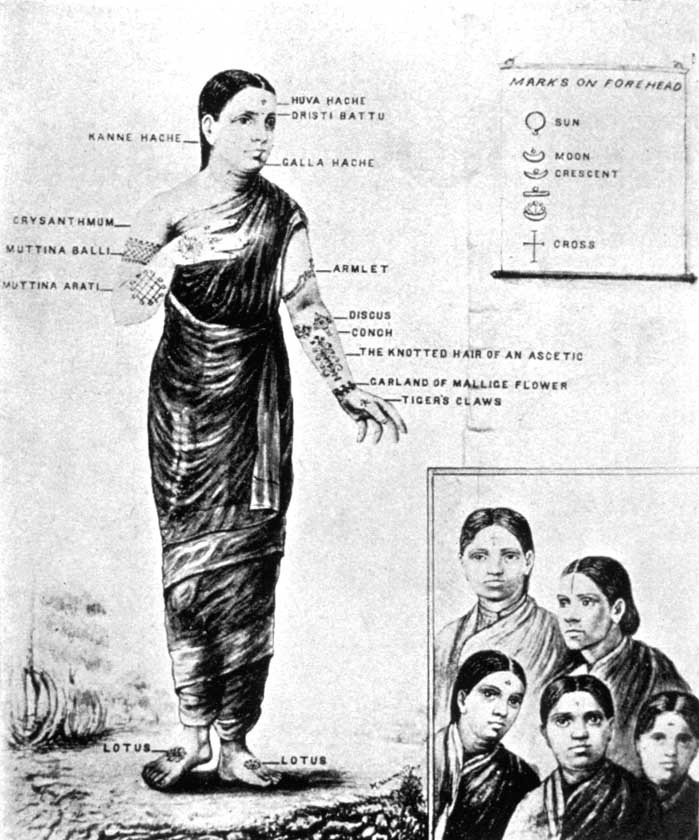

Mysore Tattooing Traditions

In the Mysore region, Korathi (Gypsy) women were the primary tattoo artists, tattooing both men and women using a pricking technique. They created intricate kolam designs and other decorative motifs. These nomadic artists traveled extensively, receiving payment in rice, plantains, betel leaves, nuts, and sometimes cash.

Tattooed women of Mysore, showcasing traditional designs

Tattooed women of Mysore, showcasing traditional designs

Korathi tattoo artist at work

Korathi tattoo artist at work

Korathi tattoo artists often chanted songs during the tattooing process to distract from the pain. These songs emphasized beauty and the enduring nature of tattoos, sometimes referencing mythological figures like Sita. The tattooing process involved tracing a design onto the skin and then pricking it in with needles. Pigments were made from soot mixed with milk or plant juices. Turmeric was applied to aid healing and enhance color. Tattoos in Mysore were believed to act as a passport to heaven, with their absence seen as displeasing to Yama, the god of death.

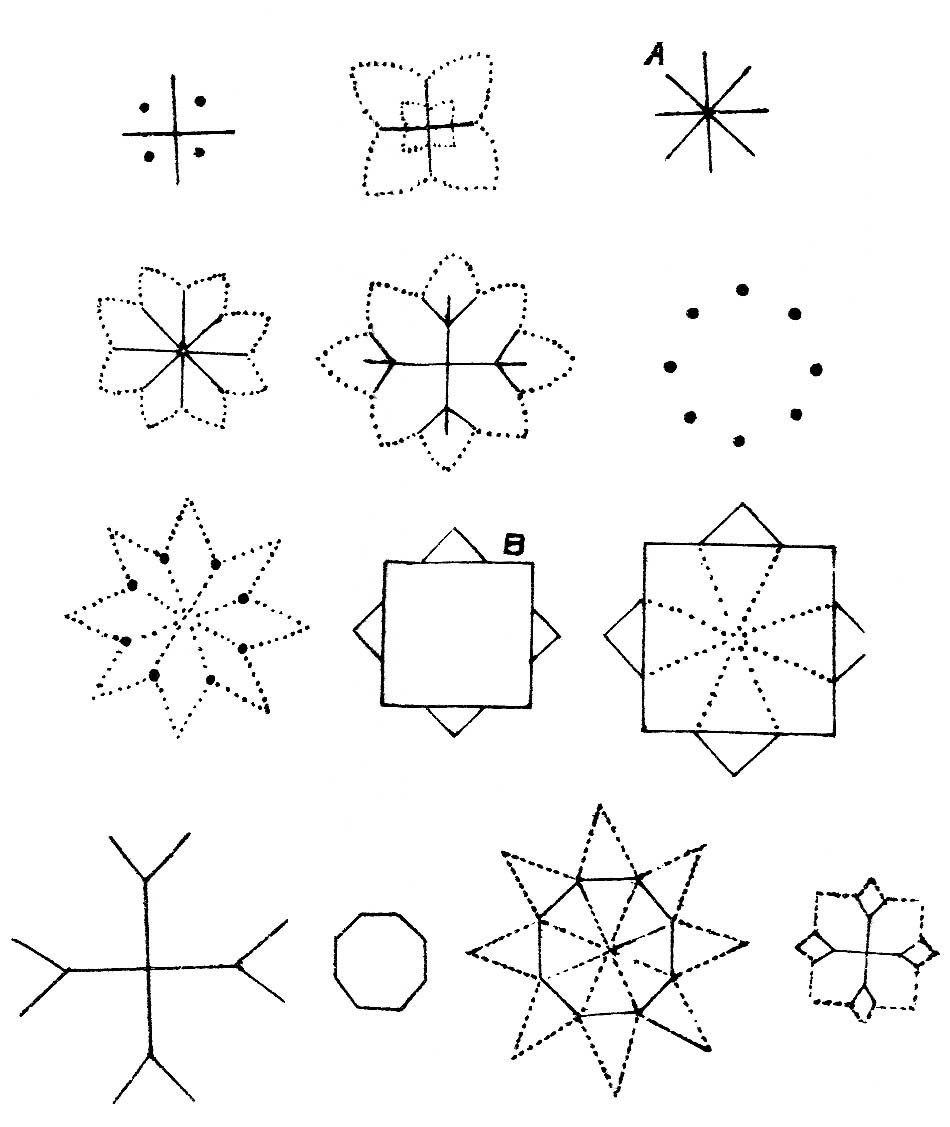

Various Kolam and protective tattoos from Mysore region

Various Kolam and protective tattoos from Mysore region

Hindu traditions in Mysore also linked tattoos to divine origins. Vishnu was said to have tattooed Lakshmi with symbols of his weapons, the Sun, Moon, and Tulsi plant for protection. Krishna was believed to have tattooed his wives with his four totems: the conch, wheel, mace, and lotus. Priests in Dwaraka applied similar marks to pilgrims.

Tattoos inspired by nature and Hindu deities

Tattoos inspired by nature and Hindu deities

Another origin story attributed tattooing to Sita, Rama’s wife, suggesting it arose from the need to identify indigenous women in case of abduction. Tribal marks, including ornaments, religious symbols, and charms, served this purpose.

Madras Tattoo Practices

Similar to Mysore, Madras had traveling female tattoo artists who served diverse communities, including Brahmin women, Hindus, Paraiyas, and Tamil Muslims. Designs ranged from simple dots and lines to complex geometrical and natural motifs like scorpions, birds, fish, and lotuses. Tattoos were placed on arms, legs, forehead, cheeks, and chin.

Madras tattoos: symbolic and decorative designs

Madras tattoos: symbolic and decorative designs

In Madras, tattooing was sometimes used for remedial purposes, applied to areas of muscular pain. A legend recounted a tragic incident where a woman died after being tattooed on the chest, leading to a superstition against breast tattoos.

Tamil Kolam Tattoos

Tamil tattooing, known as pachai kuthikiridu, was also practiced by traveling Korava women. They prepared ink from turmeric powder and Sesbania grandiflora leaves. The tattooing process involved tracing designs and pricking them into the skin. Korava artists were skilled in executing intricate patterns, even copying Burmese designs. Fees ranged from a small amount for simple marks to more for complex designs, with payment sometimes in rice in rural areas.

Tamil Kolam tattoo designs, showcasing intricate patterns

Tamil Kolam tattoo designs, showcasing intricate patterns

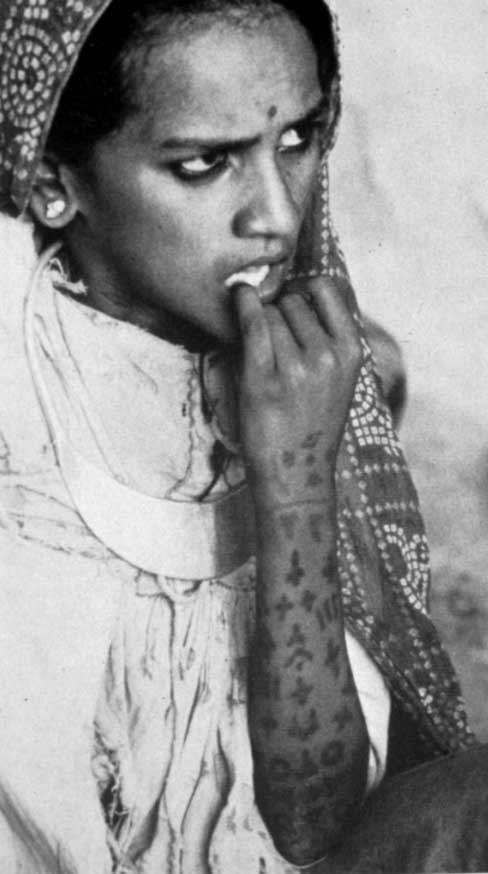

Madhya Pradesh Tattoo Traditions

In Madhya Pradesh, both men and women among the Khonds and Baigas were heavily tattooed, although male tattooing was declining a century ago. Baiga men wore moon and scorpion tattoos, sometimes for pain relief.

Bhumia and Khond girls received facial tattoos at a young age, including a horseshoe-shaped hearth symbol on the forehead, representing household duties. Puberty marked further tattooing on arms, chest, and shoulders, and marriage brought leg and thigh tattoos. Extensive tattooing was a sign of wealth due to its cost.

Bhumia facial tattoos, featuring traditional symbols

Bhumia facial tattoos, featuring traditional symbols

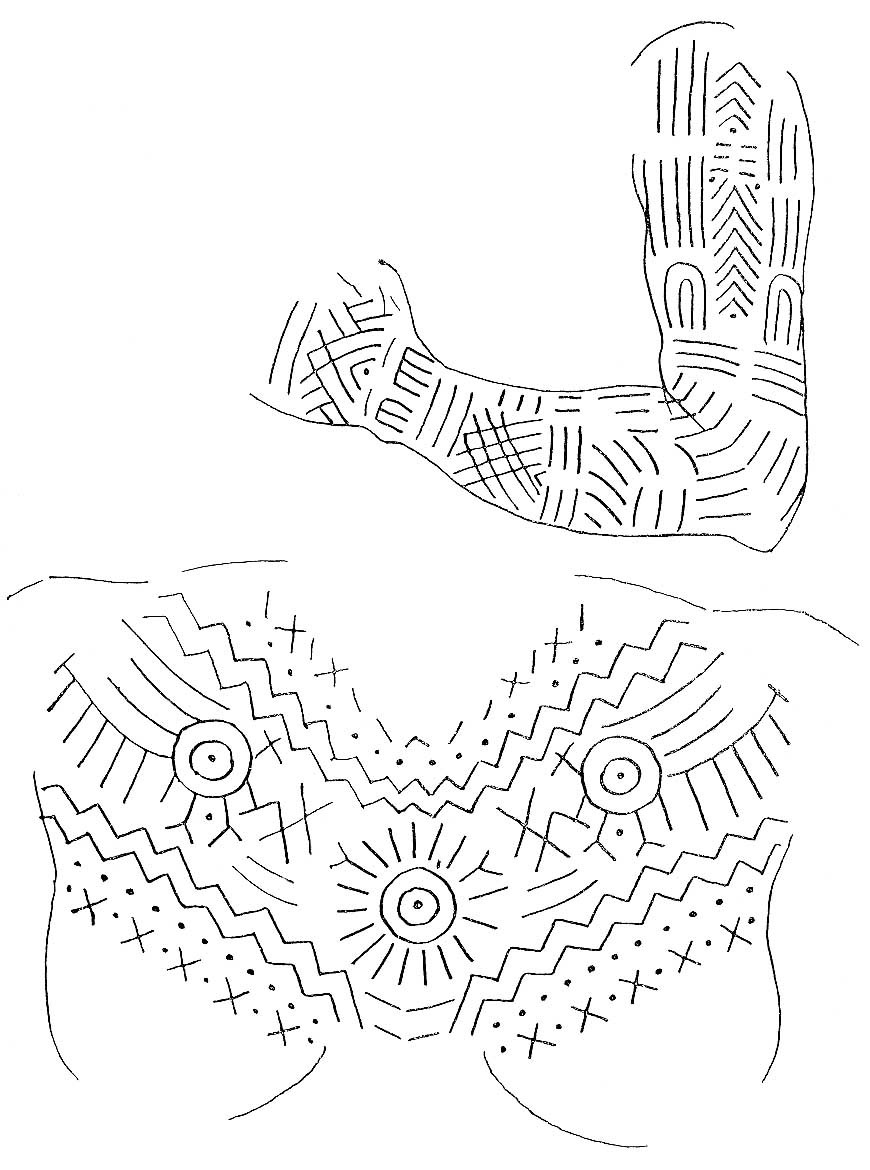

Bhumia body tattoos, showcasing extensive artistry

Bhumia body tattoos, showcasing extensive artistry

Baiga tattoos were applied by badnin tattoo artists of the Badna caste. Pigments were made from plant juices or snake skin ash mixed with oils. Electric machines are now sometimes used. Baiga women viewed tattoos as sexually expressive and permanent adornments, believed to last beyond death. Certain designs like the dhandha on the back had spiritual significance related to reincarnation. Baiga men were traditionally forbidden from witnessing tattooing, and tattooed women underwent seclusion rituals. Baiga tattoos were also believed to provide health benefits.

Bhumia leg and thigh tattoos, detailed linear designs

Bhumia leg and thigh tattoos, detailed linear designs

Baiga back tattooing, elaborate nature-inspired motifs

Baiga back tattooing, elaborate nature-inspired motifs

Satiya Bai with traditional Baiga forehead tattoo

Satiya Bai with traditional Baiga forehead tattoo

Baiga forehead tattoos for girls included a “V” mark and other lines and dots. Puberty and marriage stages brought additional designs like peacocks, baskets, turmeric roots, and various geometric patterns.

Tihro Bai's neck and chest tattoos, sun and water motifs

Tihro Bai's neck and chest tattoos, sun and water motifs

Among the Muria Khonds, women were tattooed by female relatives or Ojha women. Ink was made from charcoal dust and incense mixed with oil. Ritualistic songs and prayers were part of the tattooing process.

Baiga "eye of the cow" thigh tattoo motif

Baiga "eye of the cow" thigh tattoo motif

Khond Ghat Tattoos

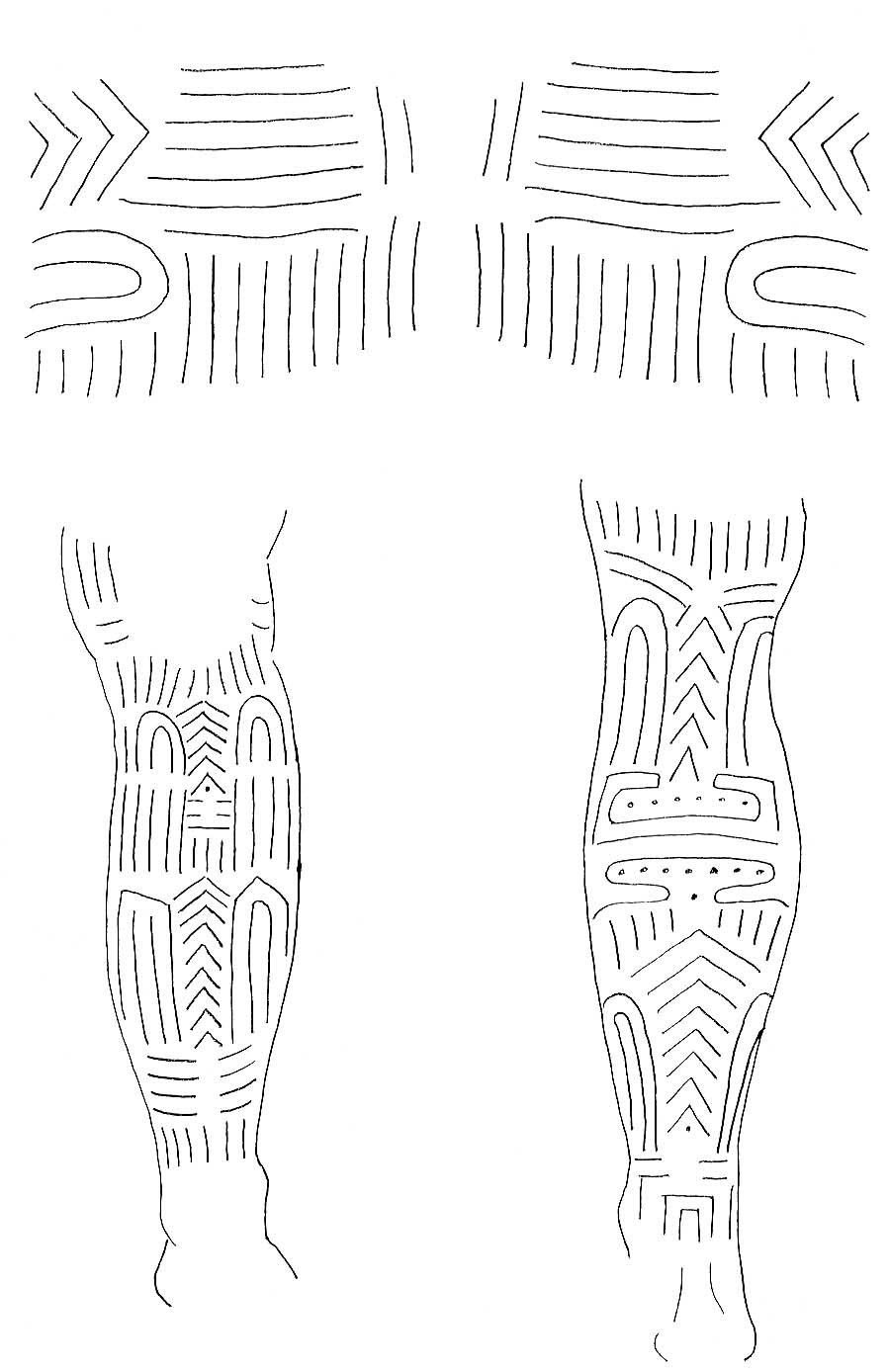

Khond women are still heavily tattooed, particularly on their legs, with sets of parallel lines called ghats or “steps,” and sometimes sankal or “chain” designs. These “indian tattoos tribal” markings are believed to strengthen legs for climbing and represent a magical protection.

Khond ghat tattoos on legs, parallel lines and geometric patterns

Khond ghat tattoos on legs, parallel lines and geometric patterns

Tattoos among Khonds, Bhumia, and Baiga tribes were originally magical protections and totem identifications. A Baiga priest described tattoos representing various deities and their protective functions for different body parts, linking them to strength, health, and well-being.

Bara Deo Tattoo, symbolic representation of a deity

Bara Deo Tattoo, symbolic representation of a deity

Origin myths of tattooing in Madhya Pradesh link it to divine figures and the roles of different communities. Tattoos were seen as essential for beauty in the afterlife and a passport to heaven. Sorcerers were tattooed with deity symbols for protection against evil magic.

Gujarat Tattoo Motifs

Tribes in Gujarat, like the Mer, believed tattoos were the only lasting possessions into the afterlife. Mer proverbs and songs emphasized the permanence of tattoos compared to worldly possessions. The Dangs shared this belief, associating lack of tattoos with divine punishment after death.

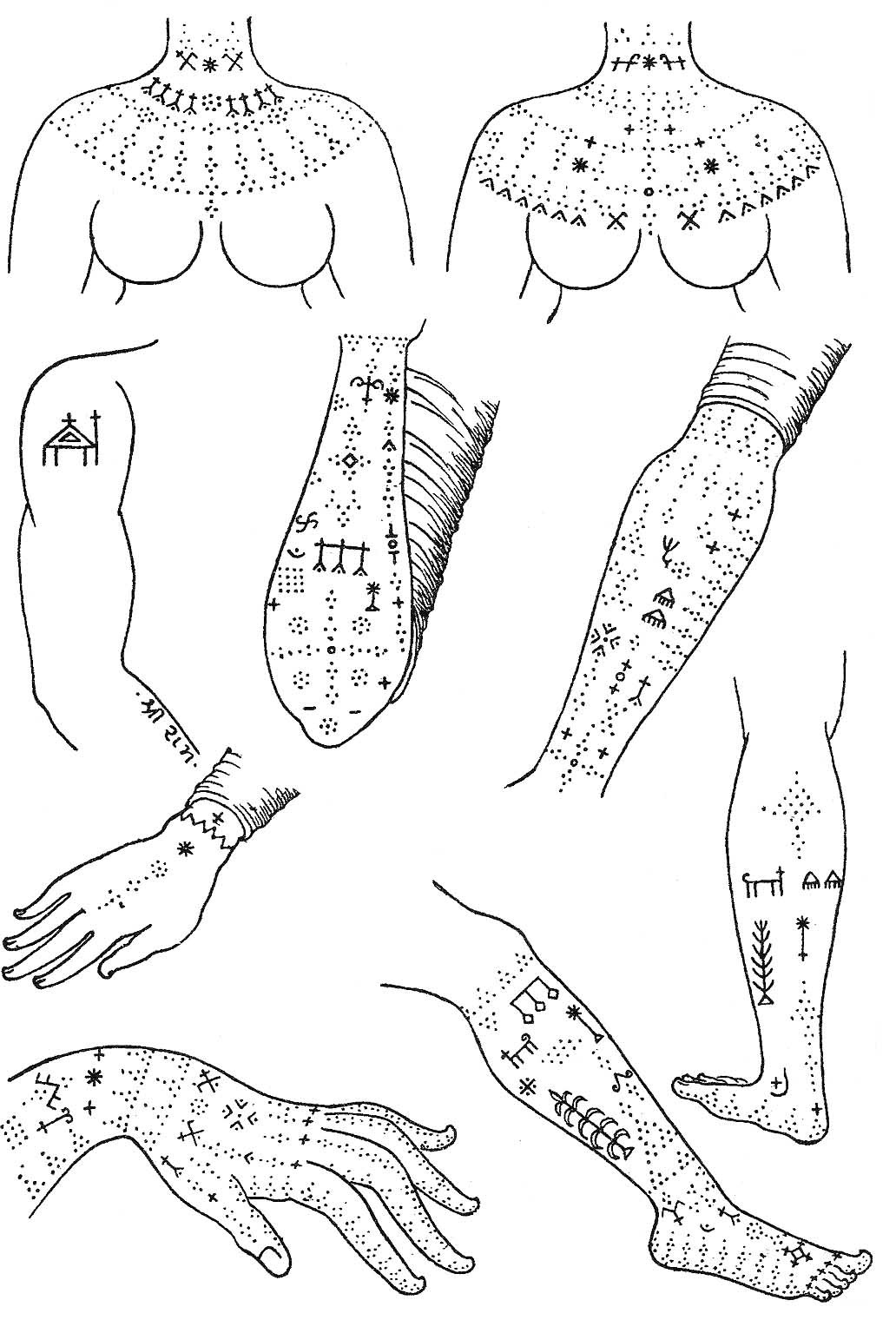

Mer body tattoos, extensive coverage and symbolic designs

Mer body tattoos, extensive coverage and symbolic designs

Mer tattoo motifs included religious and secular subjects, deities like Rama, Krishna, Hanuman, holy men, and symbols from nature and daily life. Mer men had fewer tattoos, mainly on wrists, hands, and shoulders, often featuring camels and Hindu deities. Placement on the right side might relate to the right hand’s auspicious significance in Hinduism.

Mer girls were tattooed around age seven or eight, starting with hands and feet, then neck and breast, before marriage. Untattooed brides faced social stigma. Traditional tattooing used reed sticks with needles and pigments made from soot and cow urine or plant juices. The hānsali necklace tattoo was a prominent Mer design, encompassing the neck and breasts with floral, peacock, and religious motifs. Leg tattoos featured trees, animals, and geometric patterns.

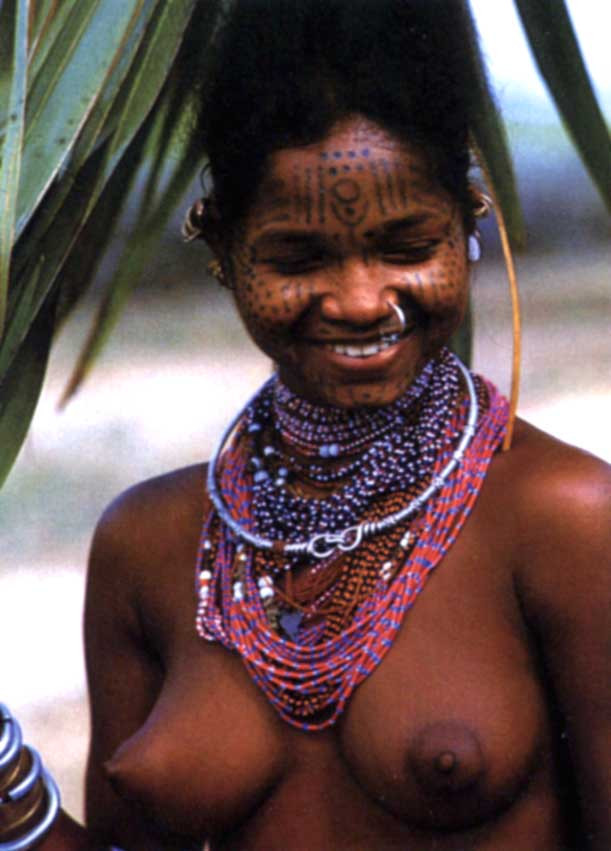

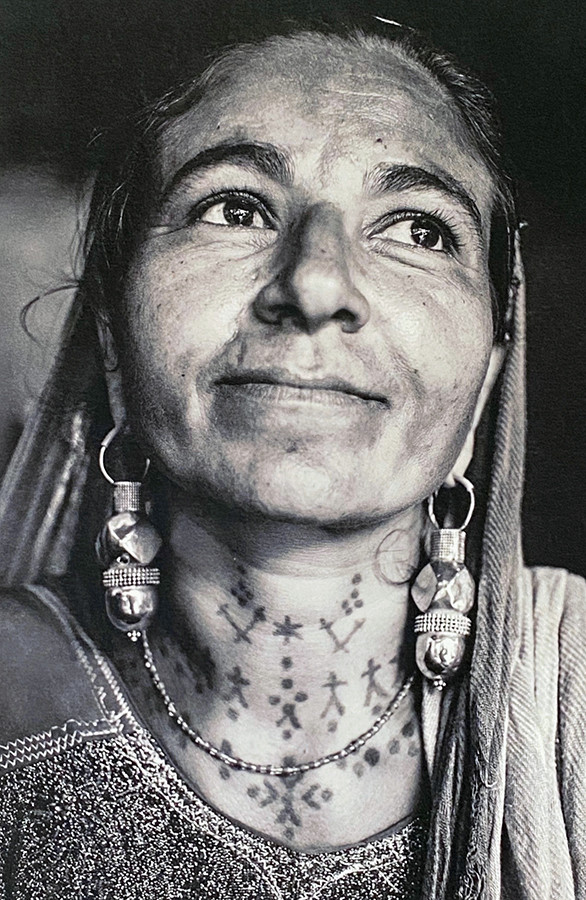

Tattooed Mer woman, Junaghad, showcasing traditional body art

Tattooed Mer woman, Junaghad, showcasing traditional body art

Experienced Mer women or women from wandering groups like Vāgharis and Nats performed tattooing. Payment was traditionally in grain, later in cash, and men increasingly used tattoo machines.

The Rabari of Kutch also practiced tattooing, with elder women as artists at gatherings. Pigments were made from lampblack and tree bark tannin or milk. Rabari tattoos covered nearly the entire body and served decorative, religious, and therapeutic purposes. Some were caste markers, while others were for fertility, attracting spouses, or magical protection. Rabari motifs often paralleled Mer designs.

Tattooed Rabari woman, displaying facial and body tattoos

Tattooed Rabari woman, displaying facial and body tattoos

Rabari forearm markings, detailed geometric designs

Rabari forearm markings, detailed geometric designs

Rabari tattoo kit, simple tools for traditional tattooing

Rabari tattoo kit, simple tools for traditional tattooing

Naga and Arunachal Pradesh Tattooing

The Naga tribes of Northeast India and Northwest Myanmar have a rich tattooing heritage. Historically headhunters, their tattooing traditions were deeply intertwined with warfare and social status. While most Nagas have converted to Christianity, animistic beliefs persist, influencing tattoo practices.

Among the Ao Naga, old women were tattoo artists, working in secluded jungle locations. Ao men were rarely tattooed, and male presence was forbidden during female tattooing. Tattooing knowledge was hereditary in the female line. Girls were tattooed before puberty as it was considered essential for marriage prospects.

Tattoo style of the Ao Naga Chungli subgroup, geometric patterns

Tattoo style of the Ao Naga Chungli subgroup, geometric patterns

The Ao tattooing process involved cane thorns and a wooden holder, hammered into the skin. Pigment was made from tree bark sap soot. Screaming during tattooing might prompt a fowl sacrifice to appease spirits.

Konyak tattooist hand-tapping a girl's legs, traditional technique

Konyak tattooist hand-tapping a girl's legs, traditional technique

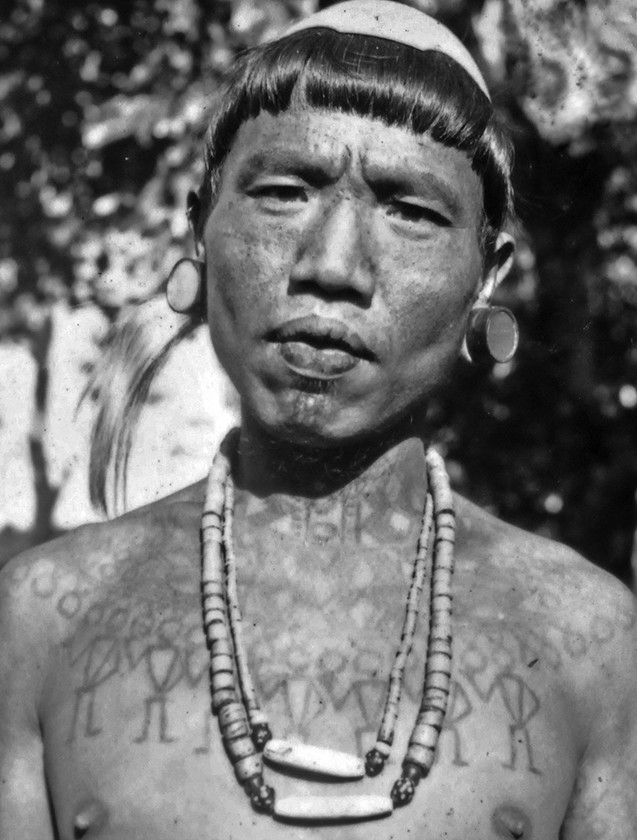

Konyak men were ceremonially tattooed upon reaching adulthood after participating in headhunting. The chief’s principal wife, an aristocratic woman, usually performed the tattooing. Facial tattooing could take a full day. Veteran warriors received neck and chest tattoos. Headhunting and tattooing were integral to Konyak male identity and status.

Konyak Naga man with traditional facial tattoos

Konyak Naga man with traditional facial tattoos

Konyak warrior Lanang, displaying facial and chest tattoos for combat and kills

Konyak warrior Lanang, displaying facial and chest tattoos for combat and kills

Konyak warrior Nokngam, faded tattoos marking warrior status

Konyak warrior Nokngam, faded tattoos marking warrior status

Even after headhunting was outlawed, Konyaks continued tattooing rituals, substituting symbolic objects for human heads. However, facial tattooing is now rare among younger Konyak men, marking a decline in the tradition.

Chang and Phom Naga men had different tattooing ceremonies and patterns. Warriors earned chest tattoos, sometimes described as “ostrich feathers” or “tiger chest,” after taking enemy heads. Further victories brought tattoos of human figures.

Phom Naga warrior Eno Henham Buchemhü, V-shaped chest tattoo symbolizing mithun horns

Phom Naga warrior Eno Henham Buchemhü, V-shaped chest tattoo symbolizing mithun horns

Chang women were tattooed only on their faces, mainly on the forehead, believed to ward off tigers. Other Naga groups believed forehead tattoos helped ancestors recognize women after death or served as afterlife currency.

Khiamniungan warrior Chellia, tattoos representing kills and warrior path

Khiamniungan warrior Chellia, tattoos representing kills and warrior path

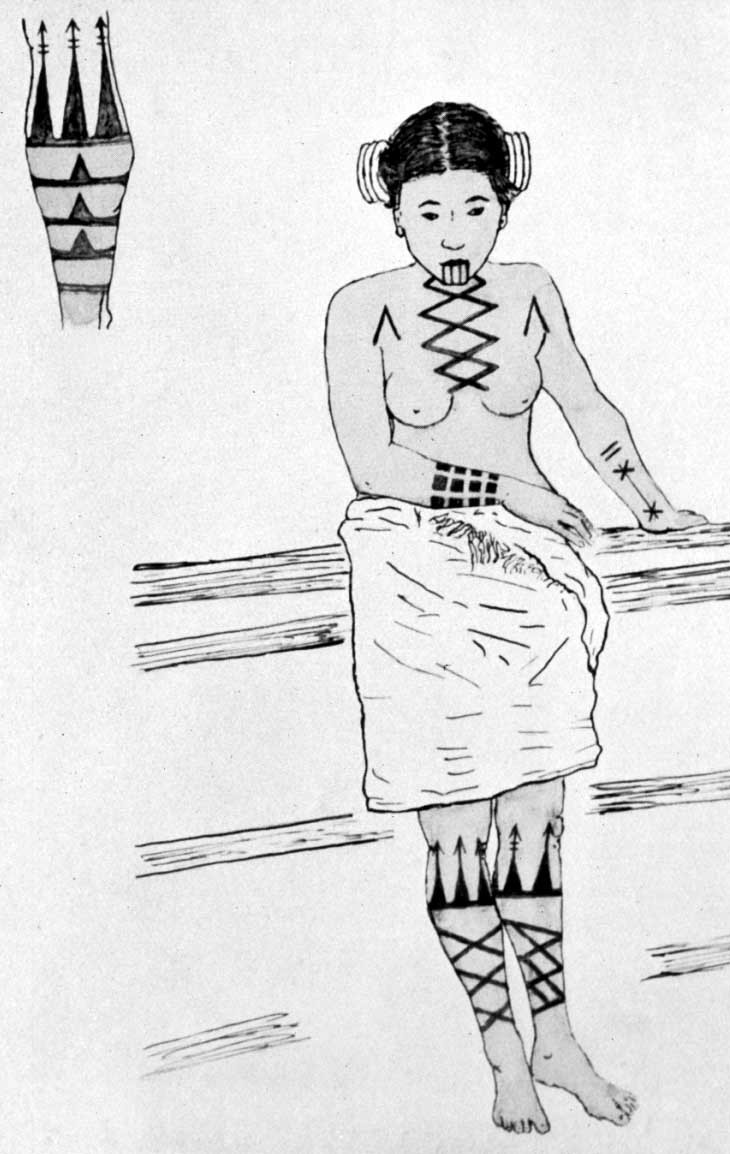

Wancho Naga women received extensive body tattoos, but no facial tattoos. Tattoo designs and placement reflected social status and life stages. Chiefly families had more elaborate designs. Women were tattooed four times in their lives, starting with navel tattoos in childhood, followed by leg tattoos at puberty, thigh tattoos after marriage, and chest tattoos after pregnancy or childbirth.

Wancho woman Apu Wangsni, navel tattoo indicating social status

Wancho woman Apu Wangsni, navel tattoo indicating social status

Wancho queen Phekhaw Wangcha, elaborate leg tattoos signifying royal status

Wancho queen Phekhaw Wangcha, elaborate leg tattoos signifying royal status

Wancho woman with chest tattoo, given after marriage

Wancho woman with chest tattoo, given after marriage

Wancho tattooing was performed by aristocratic women or “tattoo Queens.” The process used cane needles and pigment from soot and pine resin. Wancho men earned tattoos for battlefield achievements, with facial tattoos being the most prestigious warrior marks.

Wancho warrior Langtun Lukham, chest tattoo earned for headhunting

Wancho warrior Langtun Lukham, chest tattoo earned for headhunting

Wancho headhunters with neck and figure tattoos, displaying battlefield victories

Wancho headhunters with neck and figure tattoos, displaying battlefield victories

A Fading Legacy: The Future of Indian Tribal Tattoos

Indian tribal tattoos, with their diverse styles, profound meanings, and ancient origins, represent a remarkable artistic and cultural heritage. From warrior markings to magical symbols and caste identifiers, “indian tattoos tribal” art reflects a deep connection to community, spirituality, and the cosmos.

However, modernization and changing perceptions are impacting these traditions. While many young Indians continue to get tattoos, they often favor Western designs over traditional motifs. Hand-tattooing by women is being replaced by machine tattoos done by men. As younger generations adopt new trends and some view traditional practices as outdated, the future of “indian tattoos tribal” art faces uncertainty.

Despite these shifts, the rich history of Indian tattooing deserves recognition and continued study. It offers invaluable insights into indigenous cultures, belief systems, and artistic expressions. By understanding and appreciating the legacy of “indian tattoos tribal” traditions, we can ensure that this significant part of India’s cultural heritage is not forgotten and its profound value is acknowledged.

Literature

- Chowdury, J.N. (1992). Arunachal Panorama. Itanagar: Directorate of Research.

- Fischer, E. and H. Shah (1973). “Tatauieren in Kutch.” Ethnologische Zeitschrift Zurich 11: 105-129.

- Fuchs, S. (1968). The Gond and Bhumia of Eastern Mandla. Bombay: New Literature Publishing House.

- Ganguli. M. (1984). A Pilgrimage to the Nagas. New Delhi: IBH Publishing.

- Gell, A. (1998). Art and Agency. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gupte, B.A. (1902). “Notes on Female Tattoo Designs in India.” The Indian Antiquary 33: 293-297. July.

- Iyer, D.B.L.K.A. (1935). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. 1. Mysore: The Mysore University.

- Laukien, M. (2005). “Tattooing in India – The Continent of Body Art.” Skin and Ink Magazine (6) 58-76. June.

- Layard, J. (1937). “Labyrinth Ritual in South India: Threshold and Tattoo Designs.” Folklore 48: 115-182.

- Leuva, K.K. (1963). The Asur: A Study of Primitive Iron-Smelters. New Delhi: Bharatiya Adimjati Sevak Sangh.

- Mills, J.P. (1926). The Ao Nagas. London: MacMillan & Co.

- Rao, C.H. (1946). “Note on Tattooing in India and Burma.” Anthropos 37: 175-179.

- Rose, H.A. (1902). “Note on Female Tattooing in the Panjab.” The Indian Antiquary 33: 297-298. July.

- Roy S.C. and R.C. Roy (1937). The Khāriās. Ranchi: “Man In India” Office.

- Rubin, A. (1988). “Tattoo Trends in Gujarat.” Pp. 141-153 in Marks of Civilization (A. Rubin, ed.). Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History.

- Russell, R.V. and R.B.H. Lāl (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India. Vol. III. London: MacMillan and Co.

- Thurston, E. (1898). “Note on Tattooing.” Madras Government Museum Bulletin 2(2) 115-119.

- ____(1906). Ethnographic Notes in Southern India. Madras: Government Press.

- Trivedi, H.R. (1952). “The Mers of Saurashtra: A Study of Their Tattoo Marks.” Maharaja Sayajirao University Journal 1(2): 121-131.

- Verrier, E. (1939) The Baiga. London: John Murray.

- ____(1991). The Muria and Their Ghotul. Bombay: Oxford University Press.