Lisbeth Salander. The name itself conjures a myriad of images: piercing gaze, unmatched hacking skills, and of course, the iconic dragon tattoo snaking across her back. From Stieg Larsson’s gripping Millennium Trilogy to the acclaimed film adaptations, Lisbeth has captivated audiences worldwide. But beyond the gothic aesthetic and anti-social tendencies lies a complex character, and her dragon tattoo is more than just a visual statement – it’s a powerful symbol deeply intertwined with her identity.

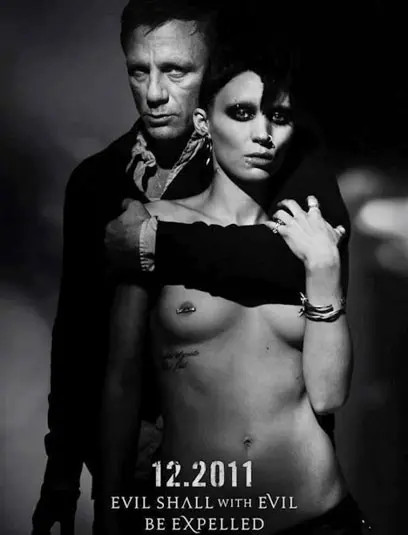

As we delve into the world of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, we encounter not just one Lisbeth, but three distinct yet interconnected iterations: the literary Lisbeth of Larsson’s novels, Noomi Rapace’s visceral portrayal in the Swedish films, and Rooney Mara’s nuanced performance in David Fincher’s American remake. While each actress and adaptation brings a unique flavor to the character, the core essence of Lisbeth, and the enigmatic dragon tattoo, remains a central point of fascination. The narrative differences between the novel and the two films, combined with varying interpretations of Lisbeth’s character, create a rich tapestry for exploration, especially when viewed through the lens of her defining ink.

Let’s first consider the source material, the book. The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo is a sprawling mystery that throws us into the lives of investigative journalist Mikael Blomkvist and the enigmatic Lisbeth Salander. My initial reading impressions, revisited for accuracy, describe it as:

The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo [is] a large scale “locked room” mystery that introduces us to dashing journo, Mikael Blomkvist, and socially awkward heroine, Lisbeth Salander. The unlikely pair join forces to investigate the decades old mystery of a missing girl, uncovering a heinous history of serial murder and sexual abuse in the process.

And further:

For all the hype, Dragon Tattoo is still a mass market genre novel. A well written one, but a genre novel all the same. Being a genre novel, it is not completely devoid of the associated cliches. The story itself is highly procedural, but to Larsson’s credit, it is also immensely readable. For a book its size, the five-hundred plus pages practically turn themselves. The final revelation is a bit of a stretch, and I found the religious angle superfluous at times, but it works well enough given the material. The book doesn’t warrant a sequel based on plot, but there are enough unanswered questions regarding the characters, especially Salander, to make the endeavor worthwhile.

While the novel’s intricate plot and character development are undeniable, it’s important to note that the book is quite exposition-heavy, particularly in its initial chapters. Details about Swedish finance laws and political history, while adding depth, can be cumbersome for some readers. Fortunately, film adaptations wisely streamline these elements, focusing on the core narrative and character dynamics. Despite its density, the novel’s page-turning quality and the allure of Lisbeth Salander made it ripe for cinematic interpretation.

Even with reservations about certain aspects of the novel, the prospect of seeing Lisbeth Salander brought to life on screen was compelling. Often, source material with flaws can translate into exceptional cinema (The Godfather being a prime example). My experience with the Swedish film adaptation shortly after reading the book was, however, somewhat underwhelming. While Noomi Rapace’s portrayal of Lisbeth was a standout, the film itself felt sluggish, struggling to translate the investigative nature of the book into an engaging visual medium.

The announcement of David Fincher directing an English-language remake sparked considerable excitement. Fincher’s ability to create tension and visual dynamism, as demonstrated in Zodiac, suggested he could inject the necessary energy into the narrative. Adding to the anticipation was the promise of a revised ending, hinting at a potentially more impactful climax than the book offered. ‘W’ Magazine reported:

The script […] was written by Academy Award winner Steven Zaillian […] and it departs rather dramatically from the book. Blomkvist is less promiscuous, Salander is more aggressive, and, most notably, the ending—the resolution of the drama—has been completely changed. This may be sacrilege to some, but Zaillian has improved on Larsson—the script’s ending is more interesting.

This news, coupled with Fincher’s directorial talent fresh off The Social Network, raised expectations for a truly compelling adaptation. The promise of a refined narrative and Fincher’s visual storytelling prowess set the stage for a potentially definitive cinematic interpretation of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo.

Opening night of Fincher’s film was an event. Even a minor pre-show kerfuffle with a fellow moviegoer couldn’t dampen the anticipation. Once seated and the lights dimmed, the film’s opening sequence, a visually arresting monochrome nightmare set to Karen O’s powerful vocals, immediately grabbed attention. The title sequence itself is a symbolic representation of Lisbeth’s inner turmoil and strength, hinting at the themes explored throughout the film. We are then plunged into Lisbeth’s world – the snow-laden Swedish landscape, her distinctive style of pressed flowers, piercings, and leather. Fincher’s meticulous direction revitalizes familiar elements, and Rooney Mara’s portrayal of Lisbeth is instantly captivating. She embodies a profound sense of damage and vulnerability, making the audience yearn to understand her, to earn her trust in a way similar to Blomkvist’s journey. There’s a palpable desire to connect with her, to offer solace, perhaps even to be dominated by her fierce independence, all underscored by the atmospheric score of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. The film’s runtime of nearly three hours feels remarkably swift, a testament to its engrossing nature.

Despite the film’s strengths, a sense of dissatisfaction lingered after the initial viewing. Perhaps expectations were too high, but it felt as though Fincher’s adaptation, while visually stunning and well-acted, hadn’t fully resolved the inherent issues within the source material. Post-viewing discussions with friends attempted to pinpoint the exact shortcomings.

One immediate observation was the misleading promise of a “completely changed ending.” This expectation had taken root, leading to anticipation for a significant narrative shift. However, as the credits rolled, the actual differences in the ending were surprisingly subtle. To clarify these nuances, a return to the source material was necessary. A review of book summaries and a re-watch of the Swedish film were undertaken, followed by a second viewing of Fincher’s remake. This comparative analysis aimed to solidify the disparate details before they blurred into an indistinct mass.

The Swedish film, directed by Niels Arden Oplev, emerged from this re-evaluation with a newfound appreciation. It contained crucial details that were surprisingly absent from Fincher’s version. The subtle foreshadowing of Plays With Fire, for instance. While the novel’s initial reveal of Lisbeth’s attempted patricide is unclear (leaning towards a later reveal), Oplev’s film incorporates brief flashbacks, culminating in a full exposition of this pivotal event. Fincher’s film, in contrast, relegates this crucial backstory to a fleeting mention during a post-coital conversation between Lisbeth and Blomkvist – “I tried to kill my father,” she states, lacking context or explanation. This omission diminishes a key aspect of Lisbeth’s character and motivations.

The Swedish film also offers a more nuanced portrayal of Blomkvist’s romantic life. While not as overtly promiscuous as his literary counterpart, he is not as emotionally reserved as Daniel Craig’s interpretation. The book provides extensive backstory on Mikael’s relationship with Millennium co-owner Erika Berger, making their rekindled affair understandable, albeit to Lisbeth’s dismay. In Fincher’s film, the romantic dynamic between Lisbeth and Mikael is emphasized, leading to a perceived betrayal when Mikael returns to Erika. Without the established history between Mikael and Erika (and his wider romantic history), this development feels abrupt. Interestingly, the Swedish film largely sidesteps Lisbeth’s jealousy, instead depicting her withdrawal as a self-protective measure rooted in fear and emotional vulnerability.

Another significant divergence lies in the acquisition of evidence against Wennerstrom. In all three versions, Lisbeth ultimately provides the crucial information. However, a key detail is omitted from the Swedish film. In both the book and Fincher’s film, Henrik Vanger’s promise to provide Blomkvist with evidence against Wennerstrom is the initial catalyst for Blomkvist taking on the Vanger case. However, the evidence initially provided proves unusable due to the statute of limitations. This plot point highlights Blomkvist’s initial motivation and sets the stage for Lisbeth’s crucial intervention. In Oplev’s film, Henrik’s promise is absent, arguably weakening Blomkvist’s initial drive and making his acceptance of the Vanger job appear less goal-oriented and more a means of escaping personal troubles. A protagonist’s clear motivation is a cornerstone of strong narrative, and this alteration in the Swedish film subtly undermines Blomkvist’s agency.

Furthermore, the nuanced detail of Blomkvist’s childhood connection to Harriet and Anita Vanger is more pronounced in the novel and Oplev’s film. This detail adds depth to Blomkvist’s personal investment in the case, extending beyond mere professional curiosity. Oplev’s film visually emphasizes the cousins’ resemblance, a subtle foreshadowing element that could have been effectively incorporated into the remake to enhance the impact of the “twist” ending.

Turning to the endings, variations exist across all three versions concerning Blomkvist’s discovery of Martin as the killer. In the novel, a photograph of Martin wearing the same jacket as the blurry figure in the parade photo is the key. The Swedish film deviates, having Blomkvist and Lisbeth deduce a pattern of Jewish victims, leading them to suspect Harald Vanger. Blomkvist’s subsequent intrusion into Harald’s home leads to an encounter with Martin, setting the stage for the confrontation. Fincher’s film also uses the Jewish victim pattern to implicate Harald, but Blomkvist’s visit to Harald’s house leads to the jacket photograph discovery, mirroring the book more closely. The Swedish film’s approach, while different, arguably builds suspense more effectively.

Martin’s demise also differs. In Larsson’s novel, Martin intentionally crashes his car into a truck. The Swedish film depicts Martin losing control and crashing, with Lisbeth consciously choosing not to save him from the burning wreckage. Fincher’s version also involves a crash, but a gasoline leak ignites the car before Lisbeth can intervene, removing the element of her deliberate choice.

The Swedish film’s ending stands out for its moral complexity. In the book, Lisbeth’s intention to “take” Martin is implied but untested. Fincher’s film has Lisbeth explicitly ask Blomkvist, “May I kill him?” but the explosion preempts her decision. Only in the Swedish film does Lisbeth face a direct moral dilemma. Her inaction, her conscious choice to let Martin burn, is a powerful moment of moral ambiguity, deepening her character and making her a more compelling, albeit flawed, heroine. This aligns with the complex symbolism often associated with dragon tattoos, representing both destructive power and fierce protection.

Finally, the “twist” regarding Harriet’s fate differs significantly. In the book and Swedish film, Harriet is alive in Australia, discovered through phone tapping. Fincher’s film alters this drastically. Anita Vanger is Harriet, a revelation stumbled upon by Blomkvist. This twist feels somewhat arbitrary in Fincher’s version. Had Blomkvist earlier confused the cousins, as in the Swedish film, this revelation would have resonated more organically. The altered ending, while different, doesn’t necessarily surpass the original in terms of narrative satisfaction, and arguably diminishes the impact of the religious motivations behind the killings, a somewhat underdeveloped aspect in Fincher’s adaptation.

The extended epilogues also vary in their effectiveness. While novels can accommodate leisurely post-denouement sequences, films are less forgiving. Both Swedish and American versions have extended epilogues, but Fincher’s feels particularly protracted, especially the “Mission: Impossible”-esque sequence of Lisbeth manipulating Wennerstrom’s finances. The Swedish film’s briefer glimpse of Lisbeth’s blonde-wigged news appearance is more concise and impactful, adhering to the cinematic principle of concluding decisively.

Ultimately, no single version of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo emerges as definitively superior. Each adaptation, book and film alike, possesses strengths and weaknesses. A hypothetical “perfect” version might Frankenstein elements from each, but even then, the underlying story, a relatively generic serial killer plot, remains a core limitation. Despite compelling characters and atmospheric setting, the narrative itself lacks profound originality. The sprawling nature of the book also dilutes the “locked room” mystery aspect in translation. Neither film adaptation fully succeeds in creating genuine suspense or red herrings, leading to a somewhat predictable resolution.

If forced to choose, a preference would lean towards a script informed by the Swedish film’s nuances (with adjustments), directed by David Fincher, and starring Rooney Mara. Fincher could also benefit from studying specific scenes in Oplev’s film, particularly in moments where the Swedish version achieves a rawer, more visceral impact. Despite Fincher’s film’s marketing emphasizing its darkness and edginess, the Swedish film often surpasses it in portraying a grittier reality. The subway attack, for example, is more brutal and unsettling in the Swedish film. Lisbeth’s laptop is not merely broken during a theft attempt, but shattered in a violent assault. The scene culminates in Lisbeth’s animalistic rage, brandishing a broken bottle. Even the initial stages of Bjurman’s abuse are arguably more intensely portrayed in Oplev’s film. And regarding the later, more graphic abuse, comparing the “finer points” of each rape scene is unproductive; both are undeniably horrific.

In conclusion, Lisbeth Salander remains a captivating enigma. Her complexity defies simple categorization. Neither Blomkvist, nor Larsson, nor Oplev, nor Fincher can fully tame her spirit. She is a force of nature – rebellious, impulsive, and deeply flawed. Perhaps this very complexity is the key to her enduring appeal. And the dragon tattoo? It’s a visual shorthand for all of this – a symbol of power, mystery, and untamed spirit etched onto the skin of an unforgettable character. The dragon, a mythical creature embodying strength and chaos, perfectly encapsulates Lisbeth Salander’s essence. As the narrative moves into The Girl Who Played With Fire, with its deeper exploration of Lisbeth’s backstory and a shift away from serial killer tropes, the hope remains that future adaptations will continue to unravel the layers of this iconic character and the powerful symbolism of her dragon tattoo.

Get The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo at Bookshop or Amazon

Get The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo Bluray at Amazon

Get The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo extended trilogy at Amazon

About the author

Joshua Chaplinsky is the Managing Editor of LitReactor. He is the author of The Paradox Twins (CLASH Books), the story collection Whispers in the Ear of A Dreaming Ape, and the parody Kanye West—Reanimator. His short fiction has been published by Vice, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Thuglit, Severed Press, Perpetual Motion Machine Publishing, Broken River Books, and more. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram at @jaceycockrobin. More info at joshuachaplinsky.com and unravelingtheparadox.com.