Inuit culture is rich with history and traditions, and among the most visually striking and culturally significant is the practice of traditional tattooing, known as tupik. For thousands of years, Inuit women have adorned their skin with intricate lines and symbols that tell stories of identity, achievement, and connection to their heritage. Today, artists like Holly Mititquq Nordlum are at the forefront of a powerful revival, bringing tupik back to the forefront of Inuit identity and sparking important conversations about cultural reclamation and pride.

Holly Mititquq Nordlum, an Inupiaq artist from Kotzebue, Alaska, has dedicated her life to promoting and preserving Alaskan Inuit culture. Her artistic journey, influenced by her artist mother, spans various mediums, from painting and sculpture to filmmaking. However, it was the rediscovery of traditional Inuit tattooing that became a central focus of her work, driven by a desire to combat negative perceptions and foster pride within the Inuit community and beyond.

Holly Mititquq Nordlum, an Inupiaq artist, stands confidently, showcasing her traditional Inuit facial tattoos.

Holly Mititquq Nordlum, an Inupiaq artist, stands confidently, showcasing her traditional Inuit facial tattoos.

Nordlum’s path took her from boarding school in Hawaii back to Anchorage, Alaska, considered the largest Inuit “village” due to its significant Inuit population. While teaching art, she realized that focusing solely on the challenges faced by Alaskan Natives, such as alcoholism and suicide, was inadvertently perpetuating negativity. She sought a more positive approach, aiming to showcase the strength and beauty of Inuit culture.

The Resurgence of Tupik: Traditional Inuit Tattooing

Driven by this desire for positive representation, Nordlum became deeply interested in tupik, the traditional Inuit practice of tattooing. Female facial tattoos, in particular, held deep historical roots within Inuit culture. Nordlum’s own great-grandmother bore these markings, and she felt a personal pull towards reclaiming this ancestral tradition. However, living in a Westernized world, she initially hesitated, aware of potential misinterpretations.

An Inuit tattoo artist, Maya Sialuk Jacobsen from Greenland, meticulously hand-tattoos Holly Mititquq Nordlum's chin using traditional techniques.

An Inuit tattoo artist, Maya Sialuk Jacobsen from Greenland, meticulously hand-tattoos Holly Mititquq Nordlum's chin using traditional techniques.

Her research into tupik began five years prior to the original article, but she found no practitioners in Anchorage who still employed traditional methods. With the support of the Anchorage Museum, Nordlum connected with Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, a tattoo artist from Greenland who preserved the ancient Inuit techniques of skin stitching and hand poking. Nordlum brought Jacobsen to Alaska to initiate a tupik training program, with the goal of revitalizing these practices within her community. Nordlum, along with two other women, trained under Jacobsen and became practicing tattoo artists in Anchorage, dedicated to these ancestral methods.

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, a Greenlandic Inuit tattoo artist, poses holding traditional tattooing tools, embodying the revival of ancient art forms.

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, a Greenlandic Inuit tattoo artist, poses holding traditional tattooing tools, embodying the revival of ancient art forms.

This revival was about more than just aesthetics; it was about community healing and reclaiming cultural identity. Nordlum explains, “The point was to bring our community together, to bring these urban Natives like myself together and bring some pride to our communities after the colonization that happened to us. Tattooing provides this vehicle for talking about these issues, not as a negative thing but just as facts. Colonization hurt our communities so how do we heal from that?”

The Significance of Inuit Tattoo Symbols

Traditionally, Inuit tattooing was a practice performed by women, for women. These tattoos were not mere decorations; they were deeply symbolic, celebrating a woman’s life journey and accomplishments. The first chin lines, for instance, marked a girl’s coming of age and entry into womanhood – a significant milestone celebrated within the community. Subsequent tattoos marked other important life events such as marriage and childbirth. The more tattoos a woman bore, the greater her life experience and accomplishments, signifying respect and status within Inuit society.

Nordlum emphasizes that this resurgence is about celebrating Inuit women and girls, a perspective that colonization had suppressed. “With colonization we lost that, but now we’re bringing it back. It’s ultimately about community.” This revival is not about rigidly returning to the past, but rather about adapting traditions to the modern world while retaining their cultural core.

Holly Mititquq Nordlum and Maya Sialuk Jacobsen stand side-by-side, symbolizing their partnership in reviving Inuit tattoo traditions across geographical boundaries.

Holly Mititquq Nordlum and Maya Sialuk Jacobsen stand side-by-side, symbolizing their partnership in reviving Inuit tattoo traditions across geographical boundaries.

As Nordlum states, “Obviously in today’s world not everything is going to equate. I’m not going to tattoo a 13-year-old, but I do talk to adults about what they want, what they can do, and what they want to accomplish. There are only a few getting chin tattoos, but when they [get any tattoos] it’s important culturally because now we live in the Western world. We’re not trying to go back to the way it was. That’s unrealistic.” Instead, it’s about embracing and expressing pride in Inuit heritage within contemporary life. “But we can be proud of who we are and walk around with it every day and that’s enough to bring some healing. That’s what I want to do: recognize we are a people that thrived here and have thousands of years of ancestry and that’s something to be proud of.”

Tupik Mi: Documenting the Tattoo Revival

The impact of colonization on Inuit communities has been profound, bringing shame and suppression of cultural practices. Nordlum’s work directly confronts this legacy. “Just walking around proud is enough. I’m not trying to go back in time; I’m just trying to bring back a little pride and community. I still want to thrive here, but in doing so also bring back a little pride and healing of our own culture.”

However, expressing this pride is not always easy. Nordlum recounts facing stares and negative reactions, especially in tourist-heavy Anchorage. While mainstream Western culture has become more accepting of tattoos, the cultural unfamiliarity with Inuit facial tattoos can still lead to prejudice. Despite these challenges, the growing number of women embracing tupik in Anchorage offers hope and resilience.

A film crew captures the Tupik Mi documentary, highlighting the cultural revival of Inuit tattooing and its impact on individuals and communities.

A film crew captures the Tupik Mi documentary, highlighting the cultural revival of Inuit tattooing and its impact on individuals and communities.

To further her mission of education and celebration, Nordlum embarked on creating a film, Tupik Mi, documenting the journey of Inuit women reconnecting through traditional tattooing. The film follows Nordlum and Jacobsen as they travel and connect with Inuit people across different regions, sharing knowledge of tupik, training other Arctic women, and exploring the personal significance of these tattoos. Tupik Mi aims to unite Inuit people from around the world, fostering a stronger sense of community and collective identity despite colonial divisions. “Bringing Inuit people from around the world together was a goal for us,” Nordlum explains. “Greenland was colonized by the Danish and we were colonized by America, but the language is still the same and the culture is still the same. This is bringing us all together to make a bigger community, and together we can make a bigger impact in the way people perceive us and the way we perceive our community.”

Cultural Sensitivity and Appropriation

While Nordlum is open to tattooing non-Inuit individuals, she maintains a crucial boundary when it comes to culturally significant Inuit designs. She reserves specific tattoos, particularly chin and finger tattoos, with deep Inuit cultural meaning, exclusively for Inuit people. This stance is a conscious effort to protect tupik from cultural appropriation and to preserve its sacredness within the Inuit community.

Holly Mititquq Nordlum tattoos a woman's arm, showcasing her dedication to reviving Inuit tattooing and sharing its cultural significance.

Holly Mititquq Nordlum tattoos a woman's arm, showcasing her dedication to reviving Inuit tattooing and sharing its cultural significance.

“The few things I’m keeping sacred are the chin and finger tattoos that have Inuit significance to them,” she states. “We’re Inuit so we’re keeping them for ourselves because that makes them special for us, and I think that’s an important element because we’ve not been special for so long, it had just been people trying to assimilate us.” Nordlum is acutely aware of the broader issue of cultural appropriation, from corporations using Inuit designs for profit without benefit to the community, to museums displaying ancient artifacts removed from their cultural context. She is a vocal advocate against such practices, using her platform to raise awareness and demand respect for Inuit culture.

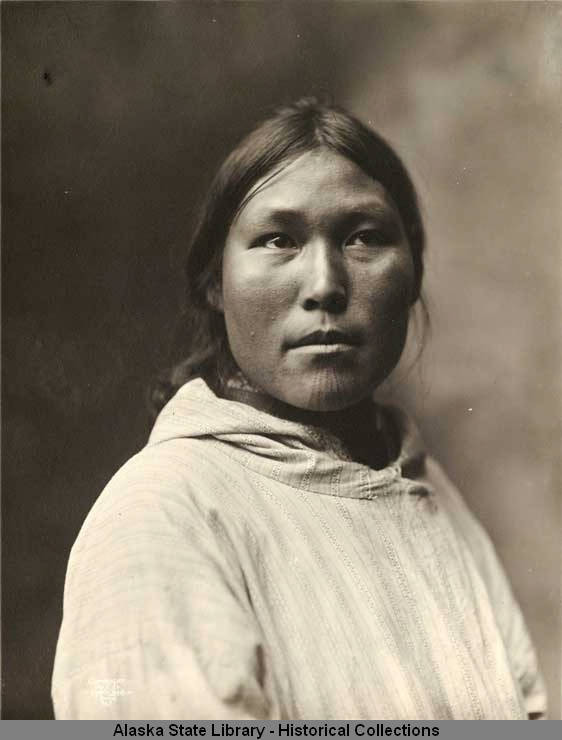

An archival image from 1903 depicts an Inuit woman with traditional facial tattoos, illustrating the historical depth and cultural continuity of Tupik.

An archival image from 1903 depicts an Inuit woman with traditional facial tattoos, illustrating the historical depth and cultural continuity of Tupik.

Nordlum encourages others who experience cultural appropriation to speak out and make their voices heard. “It’s enough to just get it out there. Tell them we’re watching,” she asserts. “Saying it and making people aware is enough. I do understand the frustration in this America that we’re living in. The frustration is unbelievable from my point of view. Everything is being taken, not just from me but from everyone.” Despite facing criticism for being outspoken, Nordlum remains committed to her mission of education, cultural preservation, and empowering Inuit people through the revival of tupik. She sees this as a crucial time for change and embraces the opportunity to be “as fearless as possible” in advocating for her culture.

The resurgence of Inuit Tattoos is a powerful testament to the resilience and enduring strength of Inuit culture. Through the dedication of artists like Holly Mititquq Nordlum and Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, tupik is not only being revived but is also becoming a vital symbol of cultural pride, healing, and self-determination for Inuit people in the 21st century.