For enthusiasts and historians alike, the story of tattooing is often shrouded in captivating myths. One of the most persistent, and arguably misleading, is what we call the “Cook Myth.” This widely circulated idea suggests that modern Western Tattoos originated solely from Captain James Cook’s voyages to Polynesia in the late 18th century. While Cook’s expeditions undoubtedly played a role in popularizing the word “tattoo” in the West, the notion that they introduced or reinvigorated the practice is a historical oversimplification.

This article delves into the fascinating and often overlooked history of western tattoos, debunking the Cook Myth and revealing the deeper, richer roots of body art in Western culture. We’ll explore evidence that tattooing was not a new phenomenon “discovered” in the Pacific, but rather a long-standing, albeit sometimes less visible, tradition within the West itself.

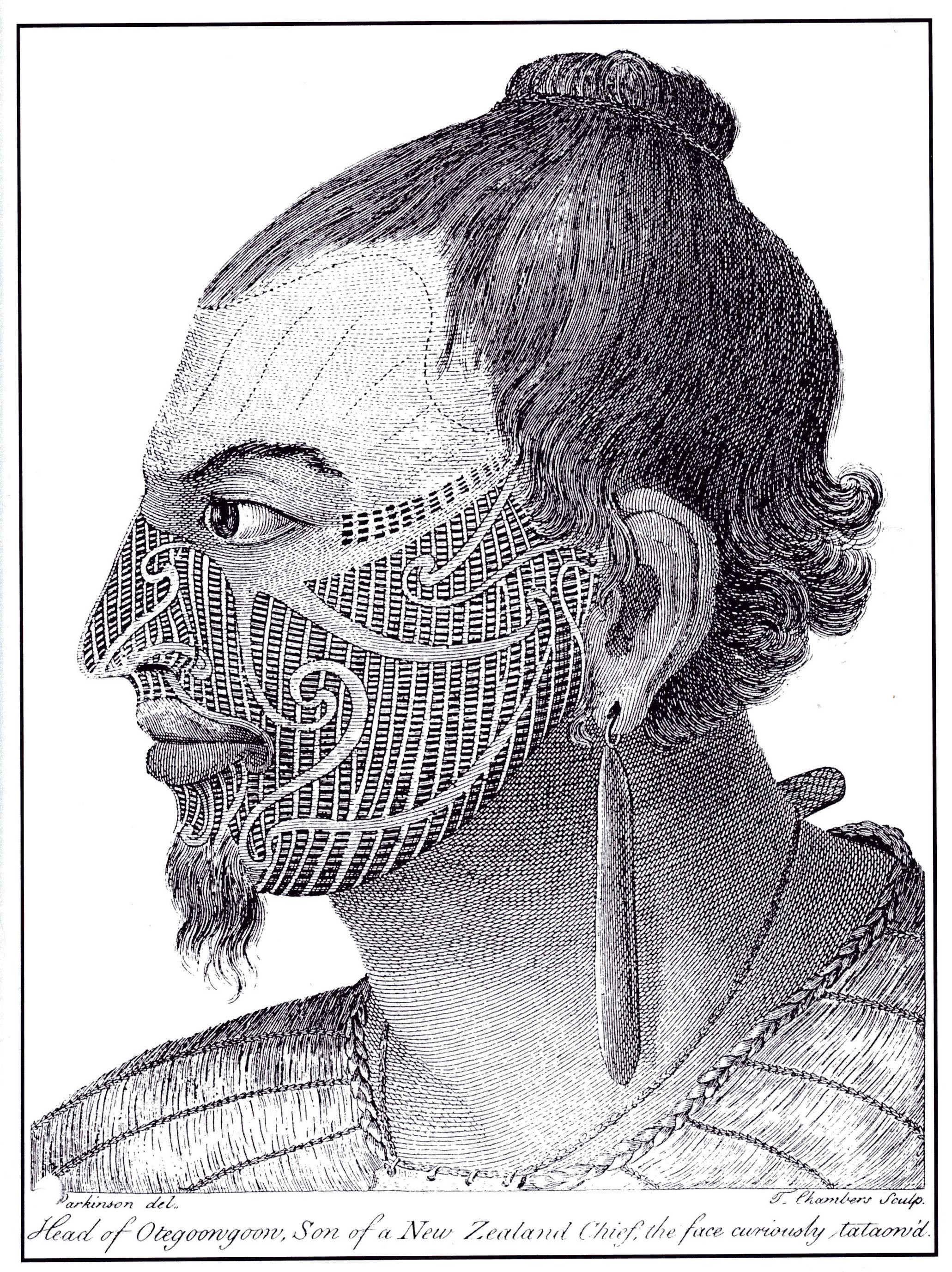

ParkinsonMaori1773001

ParkinsonMaori1773001

Classic depiction of a tattooed Maori individual by Sydney Parkinson, from Captain Cook’s first voyage, an image often linked to the misconception of tattoo origins.

Challenging the Narrative: Pre-Cook Western Tattooing

The Cook Myth often paints a picture where Westerners were largely unfamiliar with tattooing until they encountered the elaborate artistry of Polynesian cultures. However, historical records tell a different story. Long before Cook set sail for the Pacific, various forms of body marking were practiced across Europe.

Consider the observations of Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, a contemporary explorer of Cook. In 1791, while documenting Marquesan tattooing, Fleurieu drew parallels and contrasts to European practices. He noted that tattooing was not exclusive to “half-savage nations,” but was a custom known “from time immemorial” among “civilized Europeans,” specifically mentioning sailors from the Mediterranean, Catalans, French, Italians, and Maltese. These groups, he stated, used tattooing to create “indelible figures of crucifixes, Madonas, &c. or of writing on it their own name and that of their mistress.”

This account highlights several key points:

- European familiarity: Tattooing was not alien to Europeans prior to Pacific voyages.

- Diverse European groups: The practice spanned various European nationalities and cultures.

- Varied motifs: Western tattoos included religious symbols, personal names, and romantic declarations, indicating a range of motivations beyond mere imitation of Polynesian art.

- Ancient roots: Fleurieu explicitly mentions the custom’s long history in Europe.

Furthermore, historical texts reveal a range of terms used to describe tattooing in European languages before the adoption of “tattoo” from Tahitian. People were described as having their skin “pricked,” “marked,” “engraved,” “decorated,” “punctured,” or “stained.” The resulting marks were called “black marks,” “pictures,” “paintings,” “engravings,” or “stains,” often emphasized as “permanent” or “indelible.” Latin texts even used the term stigmata, while French sources utilized piquer and piquage.

These varied descriptors, found across different European languages, demonstrate that the practice of tattooing existed, even if a unified term like “tattoo” was lacking. The absence of a single word does not equate to the absence of the custom itself.

Why the Myth Persists: Language and Limited Perspectives

The Cook Myth, despite historical evidence to the contrary, has proven remarkably resilient. Several factors contribute to its persistence:

- Linguistic Bias: The very word “tattoo” originates from the Tahitian word “tatau,” brought back to the West after Cook’s voyages. This linguistic origin has led many to mistakenly assume a Polynesian origin for the practice of western tattoos as well. As anthropologist Alfred Gell pointed out, this faulty reasoning equates the origin of the word with the origin of the practice.

- Narrow Research Focus: Some historical studies have inadvertently reinforced the myth by focusing primarily on English-language sources or limiting their scope to specific groups, such as long-haul sailors in the British navy. This narrow focus can create a skewed picture, overlooking evidence from other European cultures and social groups.

- Cultural Amnesia and “Us vs. Them” Mentality: There can be a reluctance to acknowledge “taboo” practices within Western history. The idea of tattooing being “reintroduced” from exotic cultures can be more appealing than recognizing its continuous presence within Western society. This aligns with a historical tendency to view Western and non-Western cultures in opposition, with tattooing often being categorized as a “primitive” or “non-Western” practice.

Beyond Sailors: Diverse Expressions of Early Western Tattoos

To truly understand the history of western tattoos, we must look beyond the often-cited example of sailors acquiring tattoos in Polynesia. Various groups and motivations fueled the practice of body marking in the West:

- Religious Tattoos: Religious tattoos, particularly Christian symbols and imagery, have a long and documented history in Europe and the Mediterranean. Pilgrims to the Holy Land often received tattoos as permanent souvenirs of their journey and expressions of faith. These tattoos predate Cook’s voyages by centuries and represent a significant tradition of western tattoos.

- Secular Identification and Romantic Tattoos: Beyond religious and maritime contexts, evidence suggests the existence of secular western tattoos used for identification, group affiliation, or personal expression. As Fleurieu noted, romantic tattoos with names of loved ones were also part of the European tradition. Further research is needed to fully uncover the scope and history of these secular forms of body marking.

- Travelers and “Transculturites”: While sailors are often highlighted, other types of travelers also played a role in the history of western tattoos. Individuals who journeyed to different lands for trade, exploration, or other purposes sometimes adopted local tattooing practices, creating a form of “transcultural” body art that blended Western and non-Western elements.

By considering these diverse forms of tattooing, a more complete and nuanced picture of the history of western tattoos emerges. It becomes clear that tattooing was not simply imported from Polynesia in the 18th century, but rather a multifaceted practice with roots stretching deep into Western history.

Reclaiming the Narrative: A Richer History of Western Tattoos

Debunking the Cook Myth is not just about correcting a historical inaccuracy. It’s about recognizing the long and complex history of western tattoos on their own terms. It means moving beyond a simplistic narrative of “discovery” and “reintroduction” and acknowledging the diverse motivations, techniques, and cultural contexts that have shaped body art in the West.

The voyages of Captain Cook were undoubtedly a significant moment in the popularization of tattooing in the West, particularly within maritime culture. However, they were not the origin of western tattoos. The practice existed long before, evolving through various social, religious, and personal expressions. Further research into diverse historical sources, particularly those beyond English-language accounts and sailor narratives, will continue to reveal the fascinating and intricate tapestry of western tattoo history.

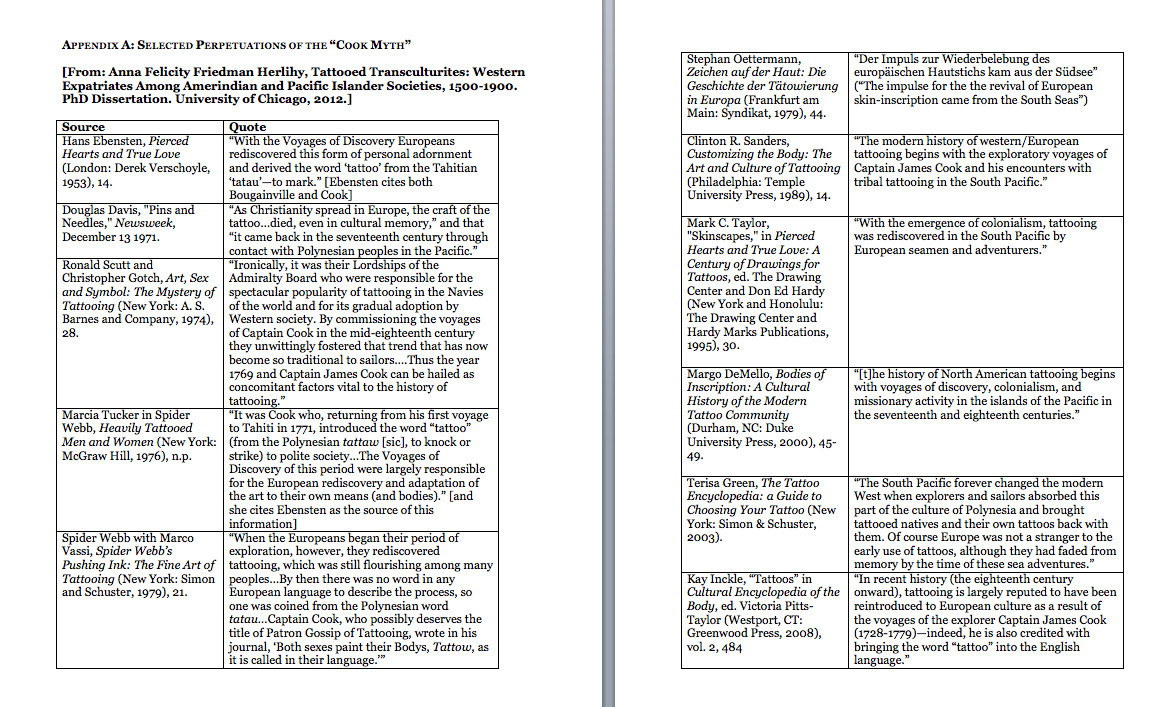

CookMythAppendix

CookMythAppendix

A chart tracing mentions of the Cook Myth in various sources, illustrating the widespread nature of this historical misconception regarding tattoo origins.