Abstract

Background: The increasing popularity of tattoos has led to a parallel rise in tattoo removal requests, driven by evolving personal identities. Laser tattoo removal is recognized as the most effective and safe method. However, the diverse nature of tattoos makes it challenging to accurately predict the number of laser treatments needed, causing uncertainty for patients.

Objective: To introduce a practical, numerical scale for evaluating tattoos and estimating the number of laser removal treatments required for satisfactory results.

Methods and Materials: A retrospective analysis was conducted on 100 patients undergoing laser tattoo removal. We developed an algorithm to score each tattoo across six categories: skin type, location, color, ink quantity, scarring, and layering. This cumulative score, termed the Kirby-Desai score, is proposed to correlate with the number of treatment sessions necessary for effective tattoo removal.

Results: A significant correlation coefficient of 0.757 was observed, indicating a strong relationship between the Kirby-Desai score and the number of treatments. Satisfactory tattoo removal was achieved in all 100 patients (p<0.001).

Conclusion: The Kirby-Desai scale offers a valuable and practical tool for predicting the number of laser tattoo removal sessions. This allows for more accurate cost estimations and improved patient expectations.

Introduction

Tattooing boasts a rich history, dating back to 12,000 BC.1 From ancient practices to modern trends, tattoos have gained widespread appeal across diverse demographics. Current estimates suggest that over 20 million individuals, representing 3–5% of the population, have at least one tattoo.2,3 However, tattoos can become sources of regret, with up to 50 percent of adults over 40 considering removal to address tattoo decisions made earlier in life.4 Laser technology has been employed for tattoo removal since the late 1970s, becoming the preferred method due to its high effectiveness and minimal adverse effects. While the decision to remove a tattoo is often straightforward, uncertainties surrounding the process persist—specifically, the number of treatments required and the likelihood of complete removal. These unknowns can add stress and financial ambiguity for patients.

Whether it’s a large, intricate design or a smaller, perhaps whimsical piece like a Kirby Tattoo, understanding the removal process is crucial. This paper introduces the Kirby-Desai scale as a tool to assess the potential success and estimate the number of laser treatments needed for tattoo removal. This scale is designed for use with quality-switched Nd:YAG (neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) or Alexandrite lasers, utilizing selective photothermolysis with treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks. Medical practitioners can use this scale during initial consultations to provide patients with a clearer understanding of the treatment plan and reduce the uncertainty associated with laser tattoo removal. Currently, patients often receive vague estimates regarding treatment numbers, entering the process without a full grasp of potential outcomes. The Kirby-Desai scale assigns numerical values to six key parameters: skin type, tattoo location, color, ink density, presence of scarring or tissue changes, and tattoo layering. Summing these parameter scores yields a total score that correlates with the estimated number of treatments for successful tattoo removal. Tattoos scoring above 15 points may present significant removal challenges and require careful evaluation by a physician to determine if laser removal is the most suitable option. To our knowledge, the Kirby-Desai scale is the first standardized tool to facilitate comprehensive laser removal assessments, aiding in the development of more precise treatment plans and enhancing patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of 100 patients treated at a private clinic (WK, Dr. Tattoff Inc., Beverly Hills, California) between July 2004 and August 2008 for laser tattoo removal. Patients were selected based on complete treatment records. Exclusion criteria included patients under 18 years of age and those who did not complete the recommended treatment sessions due to personal reasons, such as pain intolerance, appointment scheduling conflicts, or loss of follow-up.

The Kirby-Desai scoring parameters were applied as follows: skin type was scored from 1 to 6 based on the Fitzpatrick skin type classification; location from 1 to 5; color from 1 to 4; ink quantity from 1 to 4; scarring from 0 to 5; and layering from 0 to 2 (Tables 1–6).

Table 1.

Fitzpatrick Skin Type and Kirby-Desai Score

| FITZPATRICK TYPE | SKIN COLOR | CHARACTERISTICS | POINTS IN THE KIRBY-DESAI SCALE |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | White; very fair; red or blond hair; blue eyes; freckles | Always burns, never tans | 1 |

| II | White; fair; red or blond hair; blue, hazel, or green eyes | Usually burns, tans with difficulty | 2 |

| III | White or olive skin tone; fair with any eye or hair color; very common | Sometimes mild burn, gradually tans | 3 |

| IV | Brown; common in people of Mediterranean descent | Rarely burns, tans with ease | 4 |

| V | Dark Brown; common in people of Middle-Eastern descent | Very rarely burns, tans very easily | 5 |

| VI | Black | Never burns, tans very easily | 6 |

Table 6.

Tattoo Layering and Kirby-Desai Score

| TATTOO LAYERING | POINTS IN THE KIRBY-DESAI SCALE |

|---|---|

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 2 |

One investigator recorded the Kirby-Desai score for each tattoo, utilizing patient histories and photographs taken before laser tattoo removal began. The Pearson correlation coefficient between Kirby-Desai scores and the actual number of treatments administered was calculated using SPSS 16.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

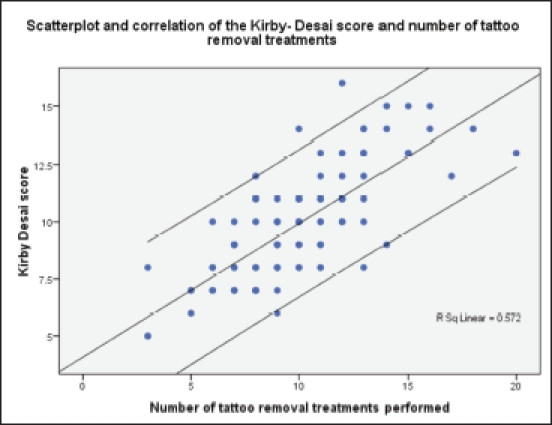

The study results indicated complete tattoo removal in all 100 patients within the subject group. The average number of treatments required was 10 (9.91±3.18), ranging from 3 to 20 sessions. This average number of treatments closely aligned with the average Kirby-Desai score of 9.87, with a standard deviation of ±2.45. Normal distributions for both datasets are illustrated in Figures 1a and 1b. A strong correlation coefficient (r= 0.757) was found between the Kirby-Desai score and the number of laser tattoo removal treatments (Figure 2). Statistical analysis using a t-ratio calculation confirmed that the sample size (N=100) was sufficient to establish a statistically significant association between the Kirby-Desai score and the number of tattoo removal treatments required (p<0.001).

Figures 1a and 1b.

Histograms showing the distribution of (a) calculated Kirby-Desai scores and (b) actual laser treatments required for satisfactory tattoo removal.

Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Scatter plot of Kirby-Desai scores versus number of tattoo removal treatments.

Discussion

Medical literature widely acknowledges that laser tattoo removal via selective photothermolysis necessitates multiple treatments. However, the precise number of treatments for individual patients has remained undefined. Our proposed scale effectively assesses and predicts the anticipated number of treatments needed to achieve complete tattoo removal. The rationale behind each scale parameter is detailed below:

Skin Type. Whether a tattoo is applied professionally or due to trauma, ink must penetrate the dermis to become permanent. Laser removal must therefore reach the dermal layer while minimizing epidermal damage. The epidermis’ basal layer contains melanocytes, which absorb laser energy, with absorption decreasing as wavelength increases.5 Skin type is thus a critical factor in laser tattoo removal. The Fitzpatrick scale, the clinical gold standard for classifying skin types into six categories based on ultraviolet radiation response, reflects skin pigmentation and melanin concentration. Melanin, like tattoo pigment, is a light-absorbing compound of similar size and thermal relaxation times—the time needed to dissipate heat absorbed during laser pulses. This is relevant to the energy needed to disrupt both melanin and tattoo pigment granules.5 While melanin and tattoo ink have different absorption spectra, successful laser tattoo removal is achievable even on darker skin, though the risk of hypopigmentation is higher. Reduced efficacy in higher Fitzpatrick skin types is due to clinicians using lower laser settings and longer intervals between sessions to minimize side effects. The Kirby-Desai scale accounts for this by scoring each Fitzpatrick skin type from 1 to 6 (Table 1).

Location. Tattoo pigment granules in the dermis interact with blood and lymphatic vessels, being engulfed by keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and macrophages. Over time, ink granules are found within dermal fibroblasts near blood vessels, beneath a layer of fibrosis, as evidenced by biopsies taken at 2–3 months and 40 years post-tattoo.4 This arrangement facilitates laser tattoo removal. Laser photons break down pigment molecules into smaller fragments that macrophages then absorb and transport via lymphatic circulation.

Blood and lymphatic supply varies across the body,6 influencing laser tattoo removal efficacy. The head and neck, with abundant lymph nodes and vascular supply, exhibit a strong immune response for ink particle phagocytosis. The trunk also has a significant vascular and lymphatic supply, second only to the head and neck. Proximal extremities have more lymphatic supply than distal extremities. The Kirby-Desai scale adjusts for these regional variations in blood and lymphatic supply (Table 2).

Table 2.

Tattoo Location and Kirby-Desai Score

| LOCATION | POINTS IN THE KIRBY–DESAI SCALE |

|---|---|

| Head and Neck | 1 |

| Upper Trunk | 2 |

| Lower Trunk | 3 |

| Proximal Extremity | 4 |

| Distal Extremity | 5 |

Colors. Tattoo inks are composed of various compounds, with precise compositions often unknown.7 Professional and amateur tattoos differ in ink composition. Amateur tattoos typically use elemental carbon from sources like cigarette ash or India ink. Professional inks use organic dyes mixed with metallic elements, often combining pigments for desired colors.8,9 Common tattoo colors include black, red, blue, green, yellow, and orange. Black pigment granules range from 0.5µm to 4.0µm and are usually carbon and iron-based. Non-black pigments can be twice as large. These differences in size and composition affect treatment needs.9 Black pigments are easiest to remove due to their small size, lack of metallic elements, and broad light absorption. Red pigments are also relatively easy to remove compared to colors like green and yellow, due to their composition of metallic and carbon elements with less titanium dioxide.10 Green, yellow, and orange pigments are more challenging to remove and thus receive higher points on the Kirby-Desai scale (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tattoo Pigment Color and Kirby-Desai Score

| COLOR OF PIGMENT(S) | POINTS IN THE KIRBY-DESAI SCALE |

|---|---|

| Black only | 1 |

| Mostly black with some red | 2 |

| Mostly black and red with other colors | 3 |

| Multiple colors | 4 |

Ink Quantity. The amount of ink in a tattoo, distinguishing between professional and amateur tattoos, influences laser removal. Amateur tattoos are often superficially placed and contain less ink, responding faster to laser treatment. Professional tattoos are deeper in the dermis and have higher pigment density.7,11 Amateur tattoos average smaller sizes (16cm2 vs. 66cm2 for professional tattoos). Amateur tattoos range from 2 to 48cm2, while professional tattoos range from 4 to 200cm2.12–14 The Kirby-Desai scale categorizes ink quantity into amateur (letters, small symbols), minimal (one color, simple design), moderate (one color, complex design), and significant (multicolored, complex design), scoring from 1 to 4 points, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Amount of Ink and Kirby-Desai Score

| AMOUNT OF INK | POINTS IN THE KIRBY-DESAI SCALE |

|---|---|

| Amateur | 1 |

| Minimal | 2 |

| Moderate | 3 |

| Significant | 4 |

Scarring and Tissue Change. Tattooing can lead to complications like granulomas, lichen planus, keloids, and psoriasis.15,16 Tattoo placement can cause increased collagen deposition and scar formation. Scarring propensity varies, but higher Fitzpatrick skin types (5 and 6) are more prone to scarring. Normal healing after tattooing involves immune cell extravasation, fibroblast proliferation, and neovascularization to restore tissue structure. However, excessive fibroblast activity can lead to permanent scarring. Tattoo pigment within fibrotic dermis is harder to remove due to cell congestion, hindering immune cell penetration.17 The Kirby-Desai scale includes scarring and tissue change (Table 5).

Table 5.

Scarring and Tissue Change Amount and Kirby-Desai Score

| SCARRING AND TISSUE CHANGE AMOUNT | POINTS IN THE KIRBY-DESAI SCALE |

|---|---|

| No Scar | 0 |

| Minimal amount of scarring | 1 |

| Moderate amount of scarring | 3 |

| Significant amount of scarring | 5 |

Layering Tattoos. Patients sometimes cover unwanted tattoos with new ones, often larger and darker to conceal the original. Tattoo ink translucency necessitates darker tones for effective cover-ups. Layered tattoos, being larger and darker, require more removal treatments. Layering adds 2 points to the Kirby-Desai scale, while non-layered tattoos receive 0 points (Table 6).

Our retrospective study showed a strong correlation between Kirby-Desai scores and the number of laser tattoo removal treatments (r=0.757, p<0.0001). Further studies with larger cohorts are needed to confirm the scale’s reproducibility, as our study group, with a 100% tattoo removal success rate, may not fully represent tattoos with greater removal challenges (scarring, layering). Multivariate linear regression analyses in future studies could further clarify the relationships between Kirby-Desai parameters.

It is well-established that multiple laser treatments are necessary for tattoo removal via selective photothermolysis. The Kirby-Desai scale enhances the art of laser tattoo removal by enabling medical professionals to better estimate the number of treatments required, leading to improved patient communication and realistic expectations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sarah Brice, Ian Kirby, Emily Holmes, Marielle Bernstein, Corrie Wahl, and Corey Ordoyne for their contributions to this paper.

References

[1] History of Tattoos. Vanishing Ink Tattoo Removal. https://www.vanishingink.com/history-of-tattoos. Accessed August 18, 2009.

[2] Armstrong ML, Roberts AE, Koch JR, Saunders JC, Owen DC, Metzger R. Tattooed Army soldiers: examining the incidence, motivations, regret, and attitudes toward the US Army tattoo policy. Mil Med. 2008;173(6):521–529.

[3] Tattoo Statistics. Tattoo Removal Facts. http://www.howtoremovetattooes.com/tattoo-statistics/. Accessed August 18, 2009.

[4] Anderson RR, Geronemus RG. Laser treatment of tattoos. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1995;14(4):296–300.

[5] Nelson JS, Margolis R, Koo J, et al. Q-switched ruby laser treatment of tattoos. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126(12):1683–1684.

[6] Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2005.

[7] Chung J, Choi M, Choi Y, Seo J, Park C, Kim J. Analysis of tattoo pigments in human skin using Raman spectroscopy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15(4):195–201.

[8] Engel E, Santoro-Höwing K, Vasani R, König B Jr, Holzle E, Pfeiffer R. Tattoo inks in human skin and laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy on tattoo biopsies. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(8):e277–e283.

[9] Leclere FM, Porte L, Geiger D, et al. Identification of pigments present in black tattoos by laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy and Raman confocal microscopy. J Raman Spectrosc. 2010;41(11):1557–1564.

[10] Bäumler W, Eibler ET, Hohenleutner U, Sens B, Sauer J, Landthaler M. Q-switched ruby laser for tattoo removal: influence of modulation, repetition rate, and pulse duration. Lasers Surg Med. 2003;33(4):237–243.

[11] Ross EV, Naseef GS, Lin G, Kelly KM, Domankevitz Y, Anderson RR. Comparison of responses of tattoos to picosecond and nanosecond Q-switched neodymium: YAG lasers. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(2):167–171.

[12] Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Tattoo removal with the Q-switched ruby laser. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19(11):974–978.

[13] Scheibner A, Kenny GM, White W, et al. Q-switched ruby laser versus trichloroacetic acid for removal of amateur tattoos. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):595–599.

[14] De Las Morenas JM, Ruiz-Rodriguez R, Leticia MS, Perez-Diaz D, Moreno-Arias GA. Tattoo removal: a comparative study between Q-switched ruby and Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2006;8(3-4):161–165.

[15] Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoo reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(4):375–376.

[16] Roberts JL. Dermal and epidermal complications of tattoos. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(1):139–147.

[17] Baalbaki EB, Awad SS. Laser tattoo removal: a review. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32(5):985–993.