For centuries, if not millennia, India has nurtured a vibrant and diverse heritage of tattooing, stretching across the vast subcontinent. From the lush, rain-soaked mountains of Northeast India, encompassing Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland, to the arid landscapes of Kutch in Gujarat, bordering Pakistan in the far west, tattoos in India have served purposes far beyond mere adornment. They have been integral to beauty standards, social identity, and even believed to accompany the individual into the afterlife.

Despite the remarkable diversity of tattooing traditions across India, comprehensive documentation remains surprisingly limited. Outside of scattered academic papers and governmental reports, much of the existing literature is found in obscure early 20th-century census pamphlets, often buried deep within archives and museum libraries. Contemporary ethnographic records are also relatively scarce. This scarcity can be attributed to the historical isolation of many tattooed communities in remote regions, coupled with societal pressures that have marginalized and overlooked these “primitive” practices in favor of more urban and “modern” lifestyles. As some observers have noted, tattoos became markers of tribal identity, unfortunately associated with inferiority in a rapidly changing India.

Nevertheless, through diligent research of older sources and firsthand accounts from Naga informants during recent visits to their region, a substantial amount of information can be pieced together. What follows is an extensive overview of traditional tattooing practices in India, both past and present, offering a glimpse into this fascinating world.

The Ancient Roots of Indian Tattooing

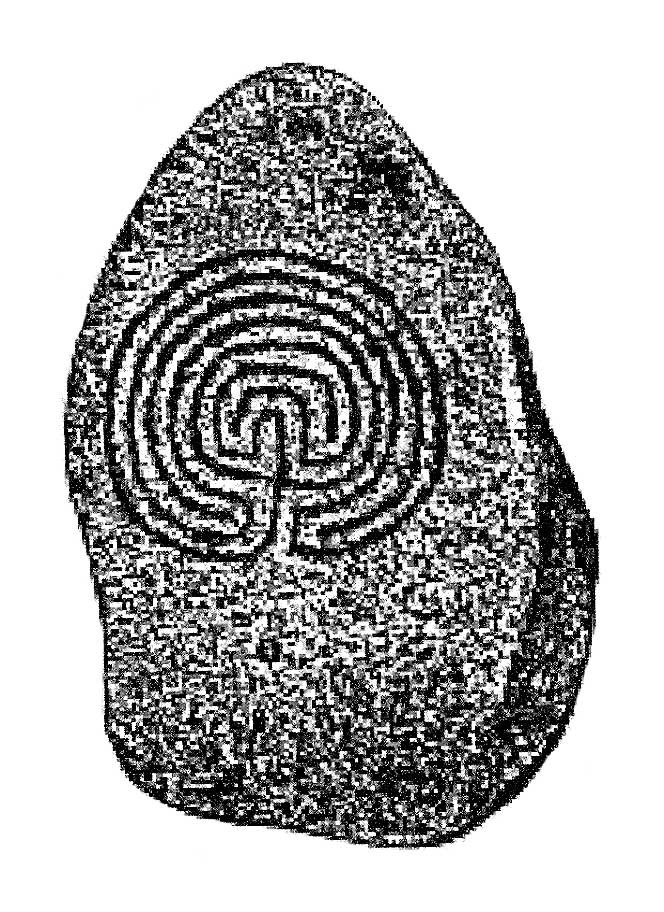

The practice of tattooing, known as godna in Hindi, is deeply rooted in India’s past, its exact age shrouded in mystery. One potential clue to its antiquity lies in the striking resemblance between labyrinth designs found in ancient petroglyphs and similar patterns in tattoos. For instance, a rock art site in Goa, tentatively dated to 2500 B.C., features a labyrinth carved into stone. Another labyrinth, dating back to 1000 B.C., is inscribed on a dolmen shrine in the Nilgiri Hills, displaying a remarkably similar configuration.

2500-year-old labyrinth cut into stone, Goa.

2500-year-old labyrinth cut into stone, Goa.

Nilgiri Hills labyrinth, 1000 BC.

Nilgiri Hills labyrinth, 1000 BC.

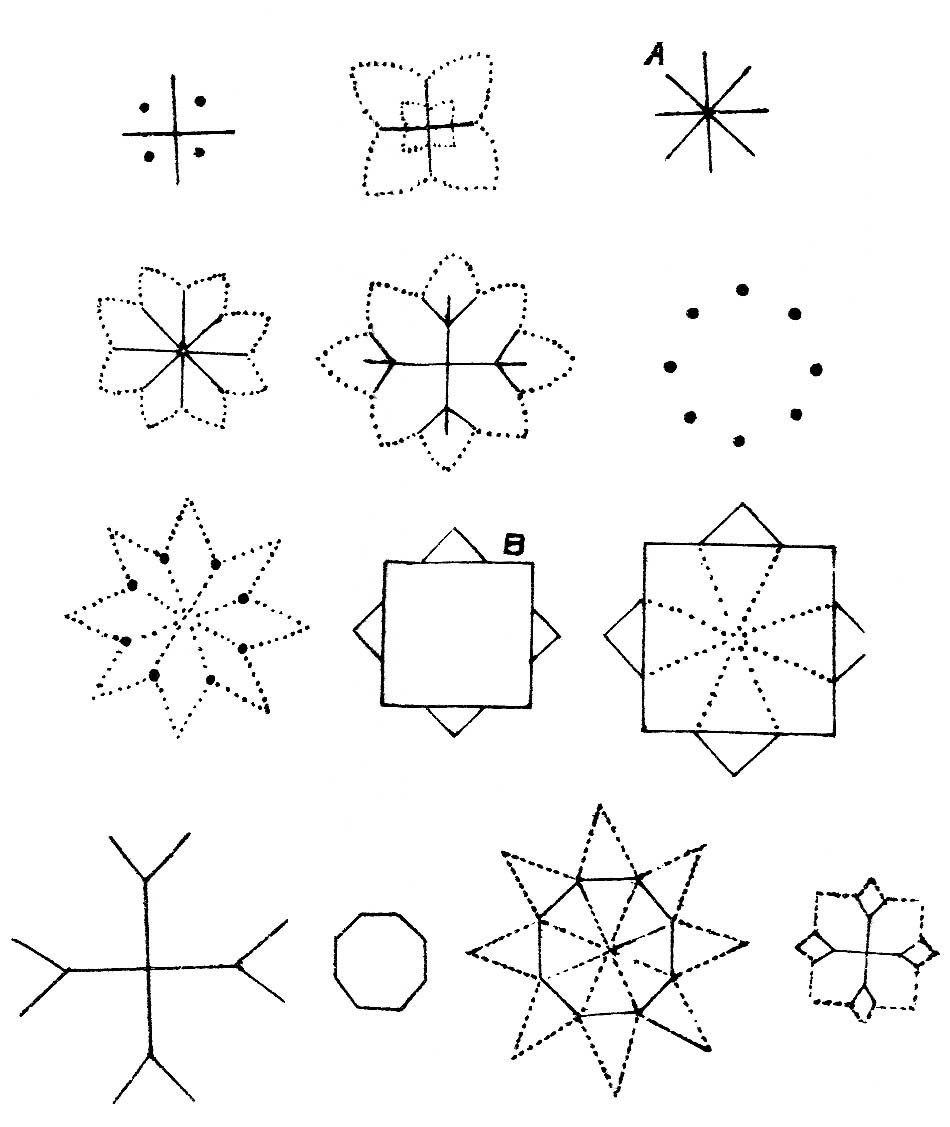

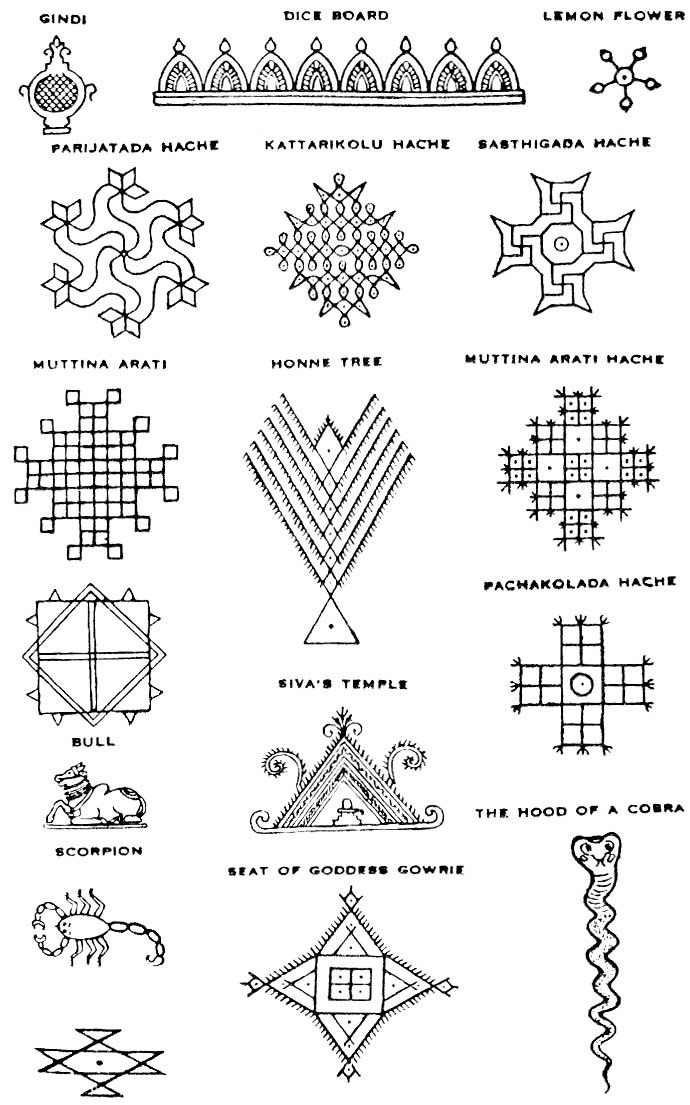

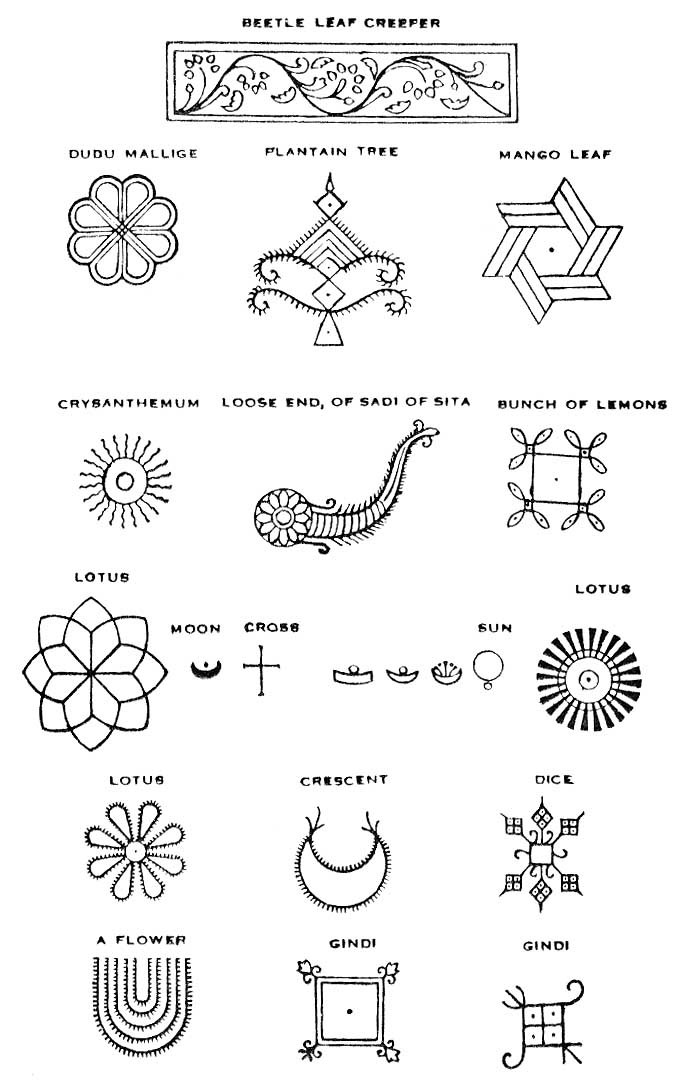

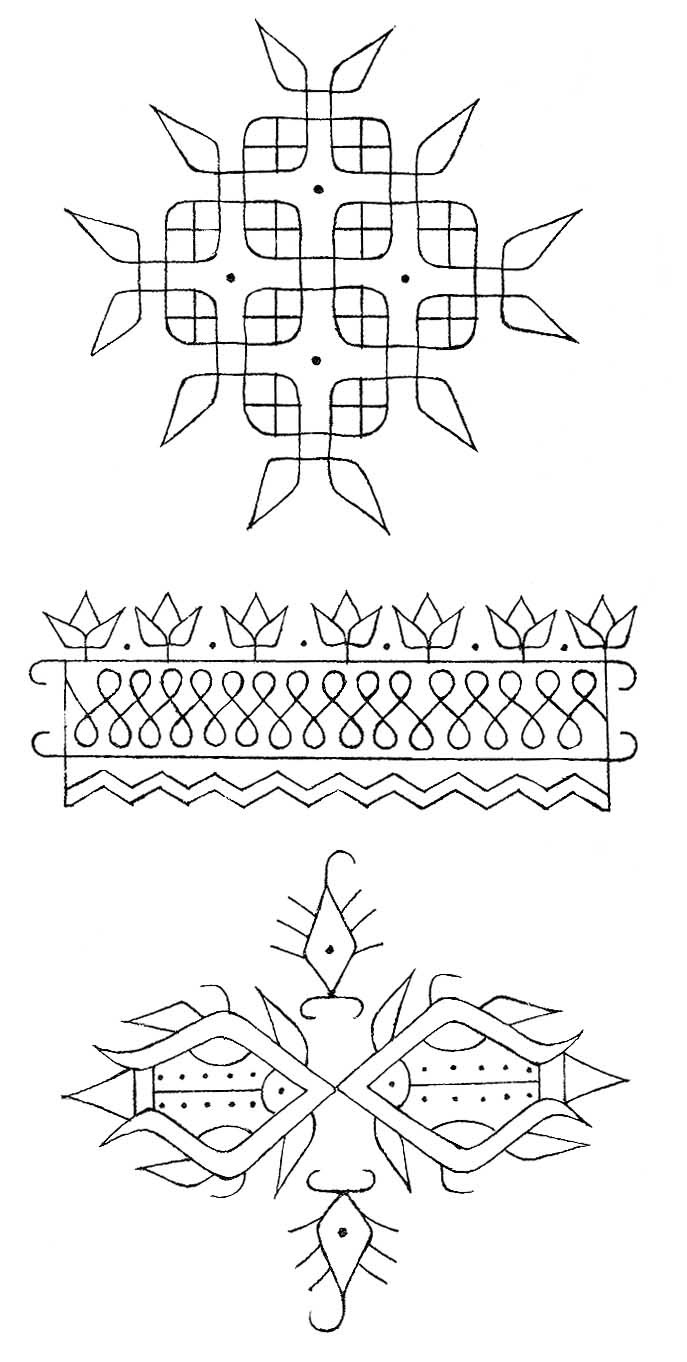

In South India, these labyrinthine patterns find a parallel in magical designs known as kolam (Figs. 3 & 4). Traditionally created by women using lime, rice powder, or other materials that flow between the fingers like sand, kolam served dual magical purposes. They were associated with the protective, fertile, and auspicious cobra deity (naga) and also possessed apotropaic power, believed to repel or ensnare malevolent spirits. Drawn at dawn, particularly during times believed to be rife with demons, kolam are intricate, symmetrical figures appearing to be formed from a single continuous line, tracing a complex maze-like path between rows and columns of dots. Typically placed near the entrance of homes, kolam were intended to provide protection and prosperity for the inhabitants.

Drawing a kolam.

Drawing a kolam.

Kolam tattoo, ca. 1920.

Kolam tattoo, ca. 1920.

Common Tattoo Designs and Their Meanings for Women

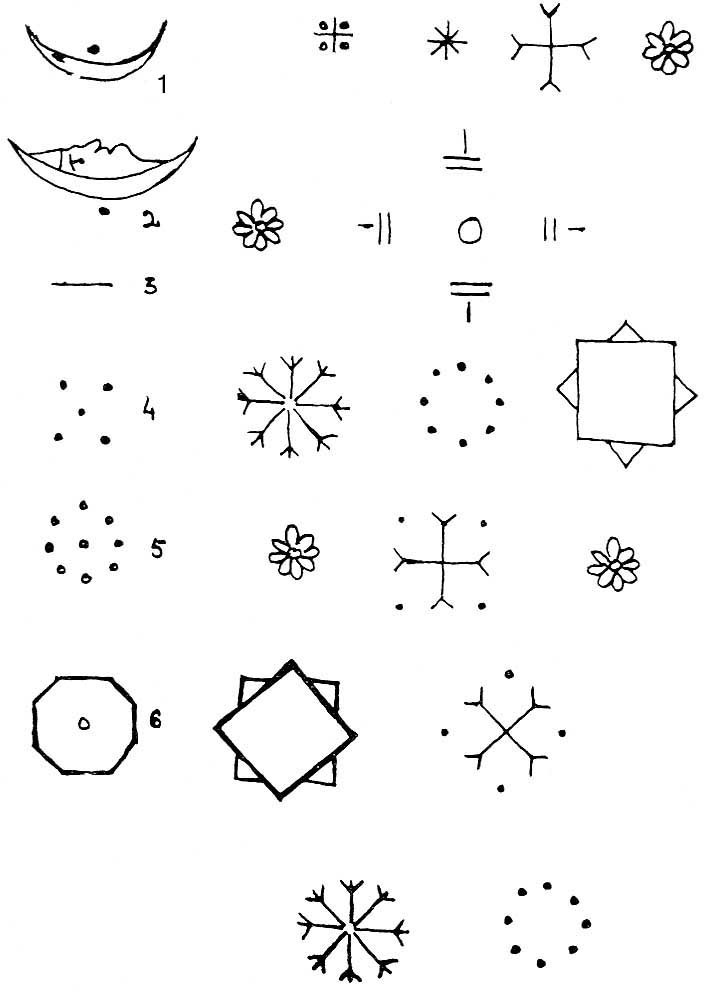

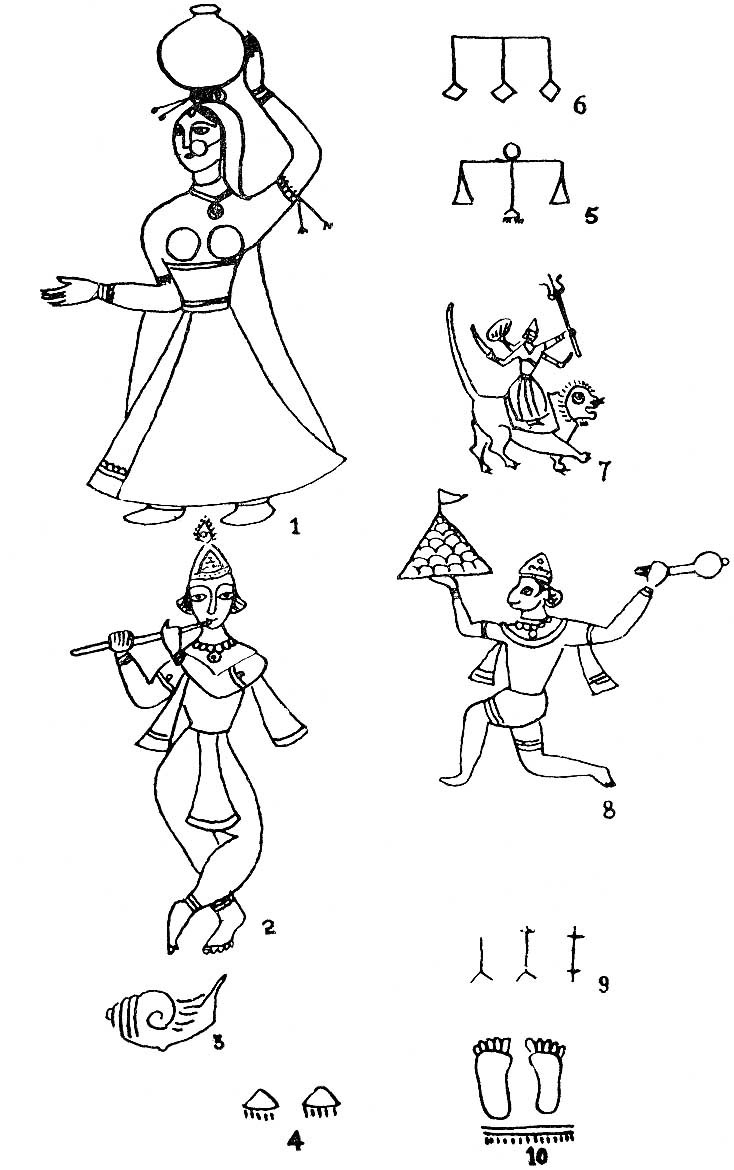

Across India, tattoos were deeply interwoven with magical beliefs. A 1902 article, “Notes on Female Tattoo Designs in India,” provides valuable insights into these beliefs. According to the article, a simple black dot, often tattooed as a mole on the forehead or chin, was thought to protect the wearer from the Evil Eye. This tattooed dot was also seen as an emblem of Chandani, the equivalent of Venus, whose celestial dance with the Moon, personified as male, symbolized the union of lovers. The Moon itself was referred to as Raktipati or Taraganapati, “King of the Night,” “Husband of the Stars.”

Figs. 1-6. Various tattoos referenced in text.

Figs. 1-6. Various tattoos referenced in text.

Rohini, the Moon’s favorite wife, was represented by a dot (•), while a crescent symbolized the Moon itself. Often, a dot within the crescent’s horns depicted the Moon’s face, sometimes even drawn in profile with another dot below representing his beloved consort – a potent symbol of marital bliss. A line tattooed between the eyebrows mimicked the red powder or ashes (angara or vibhuti) applied to that spot for protection against all evils.

The “Panch,” or five Pandava brothers, renowned for their harmonious co-existence with a single wife, were represented by four dots in a square, pierced by a central dot (see Fig. 4). This design served as a charm for domestic harmony among siblings. The nine planets, or grahs (Fig. 5), believed to exert significant influence over human destiny, were also represented in tattoo form as protection against negative influences. This was symbolized by eight dots in a circle with one in the center, mirroring the ring containing nine gems worn as a charm.

The eight-sided figure with a central circle depicted the lotus (phul), the sacred seat of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth. This symbol also represented the entire universe and was rendered in various styles (Fig. 6). Triangles held mystical significance, representing the female power, yoni. This symbolism was even reflected in religious practices, where Brahmins performing ceremonies in Sudra homes would draw a triangle in water on the ground, instead of the swastika or square used in homes of the “twice-born” castes.

Fish tattoos.

Fish tattoos.

The fish emblem, also representing yoni, was considered auspicious, originally symbolizing female power and fertility.

Caste Marks in Tattoos

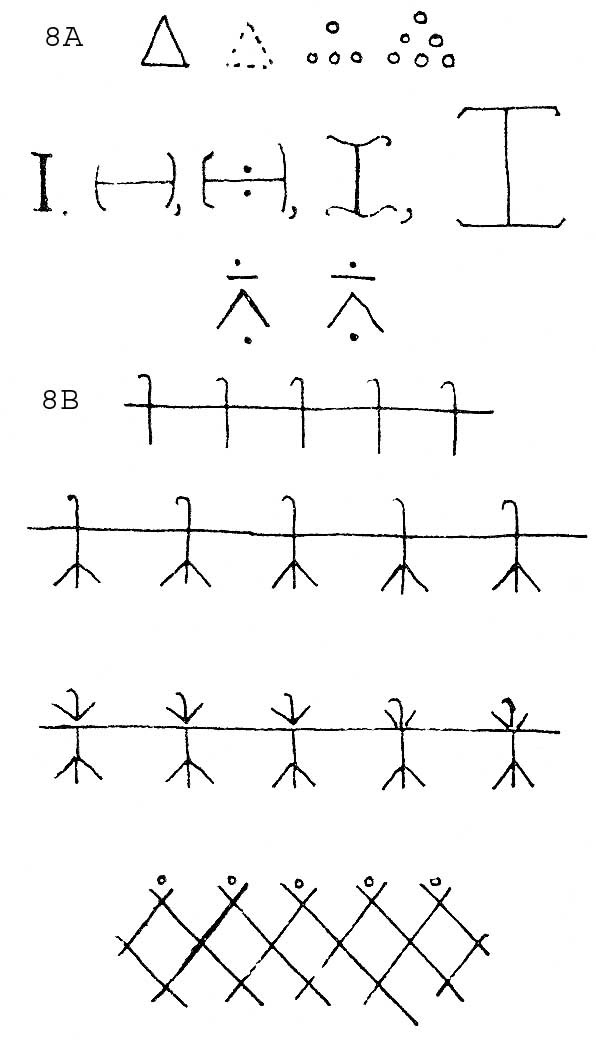

Historically, tattoos often served as indicators of profession or caste. For instance, the ateran or uteran (spindle) was once tattooed on nomadic women of spinning castes (Fig. 8A). By the early 1900s, these women had transitioned to itinerant mat or rope-makers.

Spinner and milkmaid caste marks.

Spinner and milkmaid caste marks.

Milkmaids of Krishna were identified by a specific tattoo (Fig. 8B), denoting their caste as Ahir or Goval. The number of maids depicted was consistently five. Mystic signs like A (representing the eight directions) and B (representing the eight points of the compass, formed by two intersecting squares symbolizing Heaven and Earth) also appeared in tattoo designs.

Tattoos of heaven and earth.

Tattoos of heaven and earth.

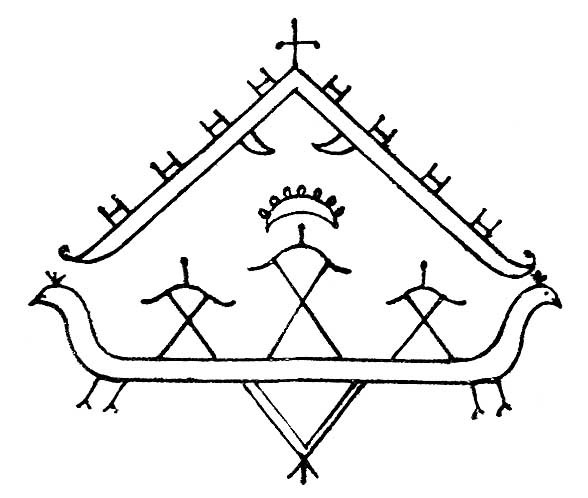

The Kanhayya’s mukat, or crown tattoo, also known as “Krishna’s Crown,” was an unmistakable caste marker around 1900. Despite being called mukat (“crown”), the design depicted the peacock throne (mayur) of Krishna. Krishna was shown seated in the center, crowned, with his wife Rukmini and brother Balaram on either side. Rajput women often bore this emblem on their arms, reflecting their aspirations for brave husbands and warrior lineage.

Krishna’s Crown.

Krishna’s Crown.

Camels, vital beasts of burden for caravans, were also represented in tattoos. Kasars, copper and brass pot traders from Nasik, featured two camels on their goddess’s pedestal. Women with camel tattoos were often identified as Banjaras, nomadic traders, with dotted and linear styles distinguishing northern and southern tribes. The Rabaris of Kutch in Gujarat also incorporated camel symbols into their tattoos, reflecting their nomadic trading lifestyle.

Other caste-specific tattoo designs from the Punjab region (early 1900s) included the madhavi (churn), ateran (spindle), camel, needle, sieve, and warrior on horseback, each denoting castes such as milkmaids, spinners, traders, cobblers, farmers, and Rajputs. These designs are believed to be remnants of “obsolete totems,” even if their original significance was no longer fully recognized.

Figurative and Protective Tattoos

Symbols like the lotus, peacock, fish, triangle, and swastika were considered lucky and even more so when tattooed on the left arm. The chakra (wheel), stars, pauchi, and “Sita’s kitchen” served as protective charms. The legend of Sita, protected by an enchanted circle around her hut (gumpha or kitchen), highlighted the protective power of such symbols.

Figurative Tattoos

Figurative Tattoos

Tattooing scorpions, cobras, bees, or spiders stemmed from sympathetic magic, believed to offer protection from these creatures. Parrots, considered lovebirds, held special charm value. Spiders were particularly noteworthy, believed to possess the power to cure leprosy.

Beyond symbolic protection, some Indian communities believed in the medicinal properties of tattoos. Mal Paharia women of Jharkhand believed tattoos maintained organ health and proper function. Muslim Maler women in Punjab believed forehead tattoos promoted safe childbirth.

The Dhelki Kharia of Jharkhand had a rich tattooing tradition, initiating girls as soon as they could walk, or sometimes delaying until ages ten or eleven, but always before marriage. Failure to tattoo a girl was a social and religious offense, requiring atonement through the sacrifice of a white fowl to Ponomosor (the Supreme Being) and drinking a few drops of its blood. Maler or Dhokar women were the tattoo artists, using a three-pronged iron instrument and pigment made from soot (preferably charred behloa wood) mixed with mother’s milk. Turmeric paste was applied post-tattooing. The ritual took place outside the home, and the tattooed girl underwent purification with turmeric and oil before re-entering, as contact with the tattoo artist was considered ritually polluting.

A Kharia origin myth recounts a story of women repelling enemies and protecting their flag during a river crossing, leading to forehead tattoos resembling flags as a commemorative practice.

Across India, a widespread belief held that tattoos accompanied the soul to heaven. Tattoo marks were seen as enduring identifiers of the soul in the afterlife.

Mysore: Gypsy Tattoo Traditions

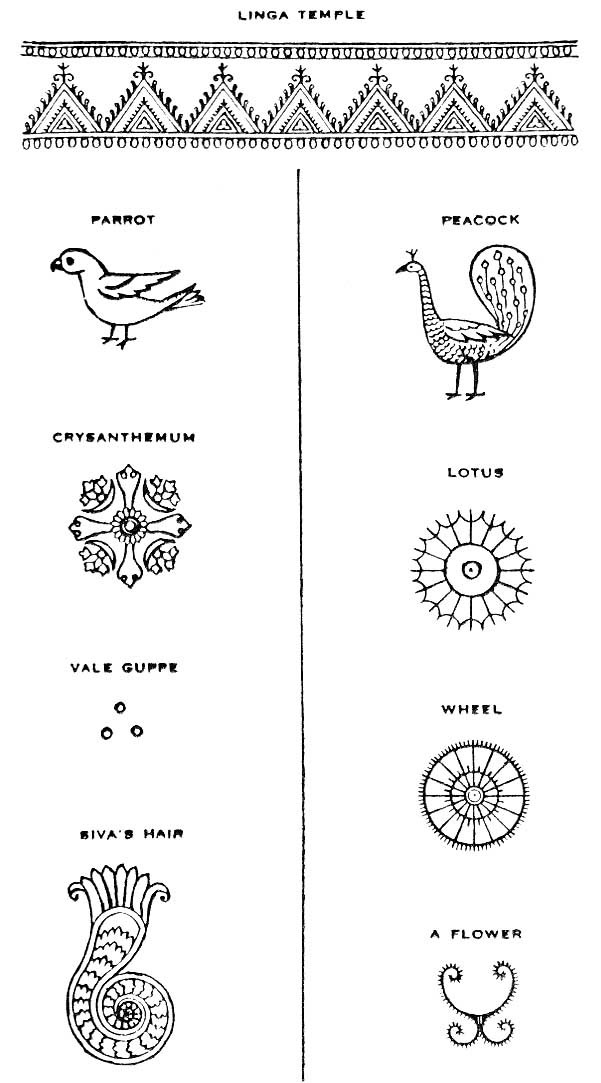

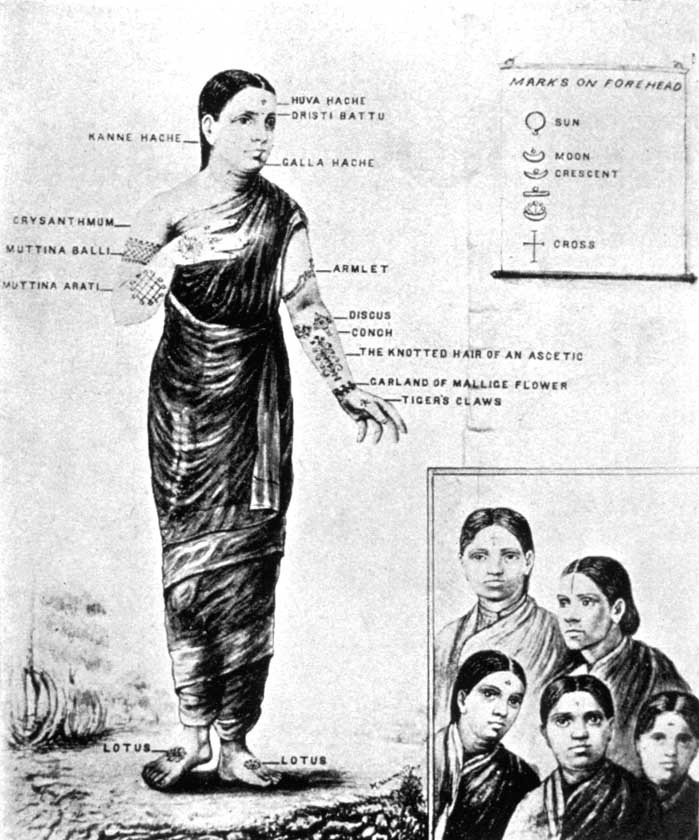

Around 1900, Korathi (Gypsy) women in Mysore practiced tattooing on both men and women using a pricking method. They skillfully inked intricate kolam designs and other beautifying motifs.

Tattooed women of Mysore.

Tattooed women of Mysore.

Mysore Tattoo Artist

Mysore Tattoo Artist

Korathi artists were nomadic, traveling widely. They were compensated with rice, plantains, betel leaves, nuts, and sometimes cash. Before beginning, the artist would bless the client. During the tattooing process, they chanted nursery rhymes or Gopika Gita songs to distract from the pain. One example of a Korathi tattoo song included verses like:

“Stay, darling stay – ’tis only for an hour,

And you will be the fairest of the fair…”

The tattooing tool consisted of multiple needles bound together. Patterns were chosen from drawings and traced onto the skin with ink before being pricked in. The skin was cleaned with cold water, ink applied, and coconut oil and turmeric powder used to alleviate pain, brighten color, and prevent swelling. Some tattoo pigments were known to ancient Indian doctors, suggesting a possible connection to medicinal tattooing for ailments like rheumatism.

Various kolam and other protective tattoos.

Various kolam and other protective tattoos.

Pigments were made from betel leaf juice soot mixed with cow’s milk or breast milk, soot from earthen pans mixed with breast milk, or soot from turmeric-coated tiles. Clients believed tattoos served as a passport to heaven and forgiveness of sins, while lack of tattoos risked Yama, the god of death’s displeasure. Some tattoos were considered talismans for wealth. In Mysore, untattooed Hindu women were considered unclean, restricted from touching corn or serving food.

Hindu traditions from around 1910 attributed tattoo origins to divine figures. Vishnu was said to have tattooed Lakshmi’s hand with his weapons, the Sun, Moon, and Tulsi plant for protection. Krishna supposedly tattooed his wives with his four totems: sankh (conch), chakra (wheel), gada (mace), and padma (lotus). Priests in Dwaraka marked pilgrims with these symbols.

Vishnu and Lakshmi Tattoo

Vishnu and Lakshmi Tattoo

Another tradition linked tattooing to Sita, Rama’s wife, suggesting it originated from fear of abduction of indigenous women. Tribal marks, including ornaments, religious drawings, charms, and symbols, aided in identification.

Other Hindu-related tattoo symbols included dots for Lakshmi (wealth), Sita for chastity, peacocks for royalty, fish for fertility, and combs for marital happiness. Ganesh worshippers undergoing tattooing rituals involved offering coconuts and burning incense to ward off the Evil Eye.

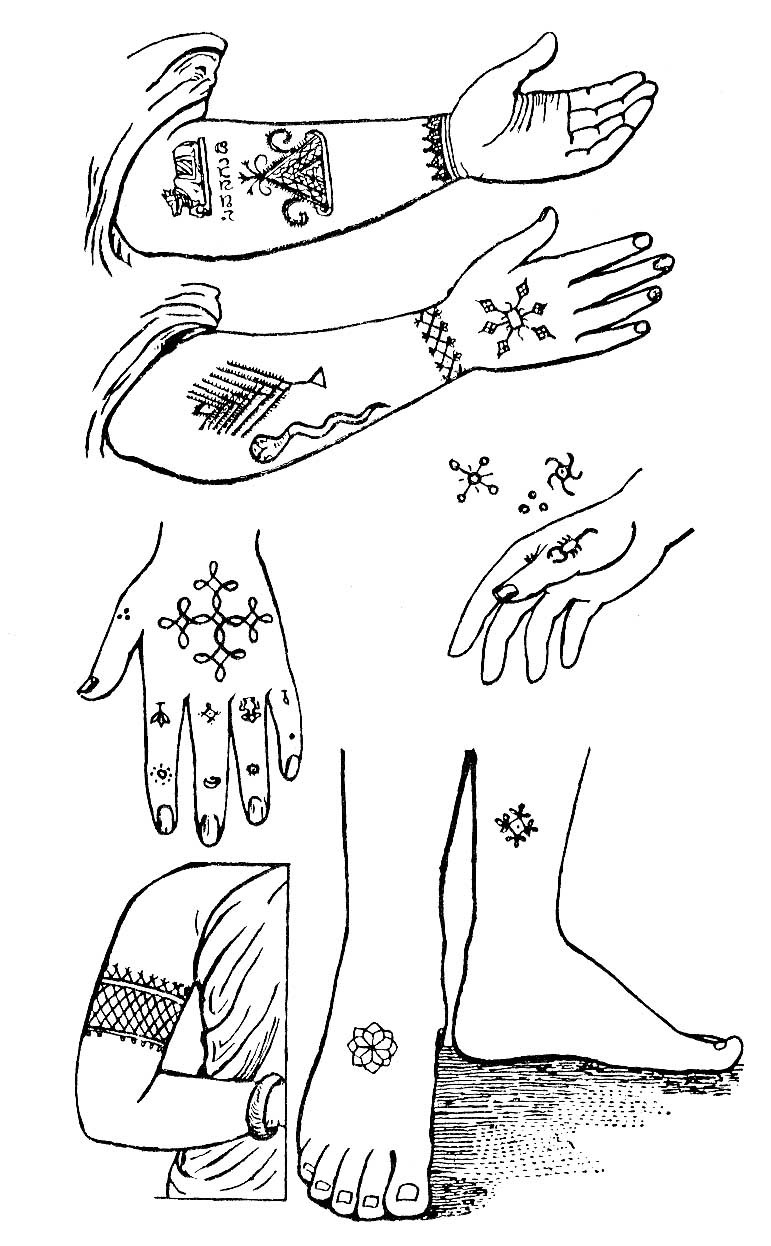

Madras: Traveling Tattoo Artists and Remedial Tattoos

In Madras, like Mysore, female tattoo artists traveled the countryside, departing Madras during harvest season and visiting neighboring districts, including Pondicherry and Cuddapah. Their clientele included Brahmin women, Hindus, Paraiyas, and Tamil Muslims. Patterns ranged from simple dots and lines to complex geometric and natural motifs like scorpions, birds, fish, and lotuses, many symbolizing luck. Common tattoo locations for women included arms, forelegs, forehead, cheeks, and chin.

Madras tattoos: 1) Pāniāri, 2) Krishna, 3) Conch, 4) Feet of Rama, 5-6) Kāvad, 7) Kali, 8) Hanuman, 9) Holy Men, 10) Footprints of Ramdevji.

Madras tattoos: 1) Pāniāri, 2) Krishna, 3) Conch, 4) Feet of Rama, 5-6) Kāvad, 7) Kali, 8) Hanuman, 9) Holy Men, 10) Footprints of Ramdevji.

Tattooing was sometimes used remedially for muscular pain and other ailments, applied over joints or affected areas. One account describes a Bedar man with a dislocated shoulder tattooed with Hanuman to relieve pain.

A legend recounts a Paraiya woman who died after requesting a bodice tattoo, the needles puncturing her heart, leading to a superstition against breast tattooing.

Tamil Kolam Tattoos and Korava Artists

Tamil kolam tattoos.

Tamil kolam tattoos.

Tamil tattooing, known as pachai kuthikiridu (“pricking with green”), was practiced by traveling Korava women, who were also fortune tellers. Their ink was made from turmeric powder and Sesbania grandiflora leaves, ground together, rolled into a wick, and burned in a castor oil lamp under an earthen pot to collect soot, which was then mixed with mother’s milk or water. The tattooing tool was similar to Mysore, using needles bound together.

Patterns were selected from paper drawings created by the artist, traced onto the skin, and then pricked in. Afterward, the tattoo was washed, pigment rubbed in, and oil and turmeric powder applied for pain relief, color enhancement, and swelling prevention. Korava artists were skilled at intricate patterns but required designs for initials or names. By 1910, they were even copying complex Burmese designs. Fees ranged from a quarter anna for a dot to twelve annas for complex designs, with rural payment often in rice.

Madhya Pradesh: Tribal Tattoos of Khonds, Bhumia, and Baiga

A century ago in Mandla, both Khond and Bhumia men and women were heavily tattooed, though male tattooing was declining. Baiga men wore moon (chandrama) tattoos on hands and scorpion (bichhu) tattoos on forearms, sometimes tattooing painful areas to treat rheumatism.

Bhumia and Khond girls were first tattooed as young children, with forehead, temple, and right cheek markings. The forehead tattoo, a horseshoe-shaped hearth symbol (chulwa) above the nose, symbolized household duties. Temple and cheek tattoos (dipa) were lines and dots. Puberty brought arm, chest, and shoulder tattoos, and pre- or post-marriage tattoos on legs and thighs. Extensive tattooing was a sign of wealth.

Bhumia facial tattoos.

Bhumia facial tattoos.

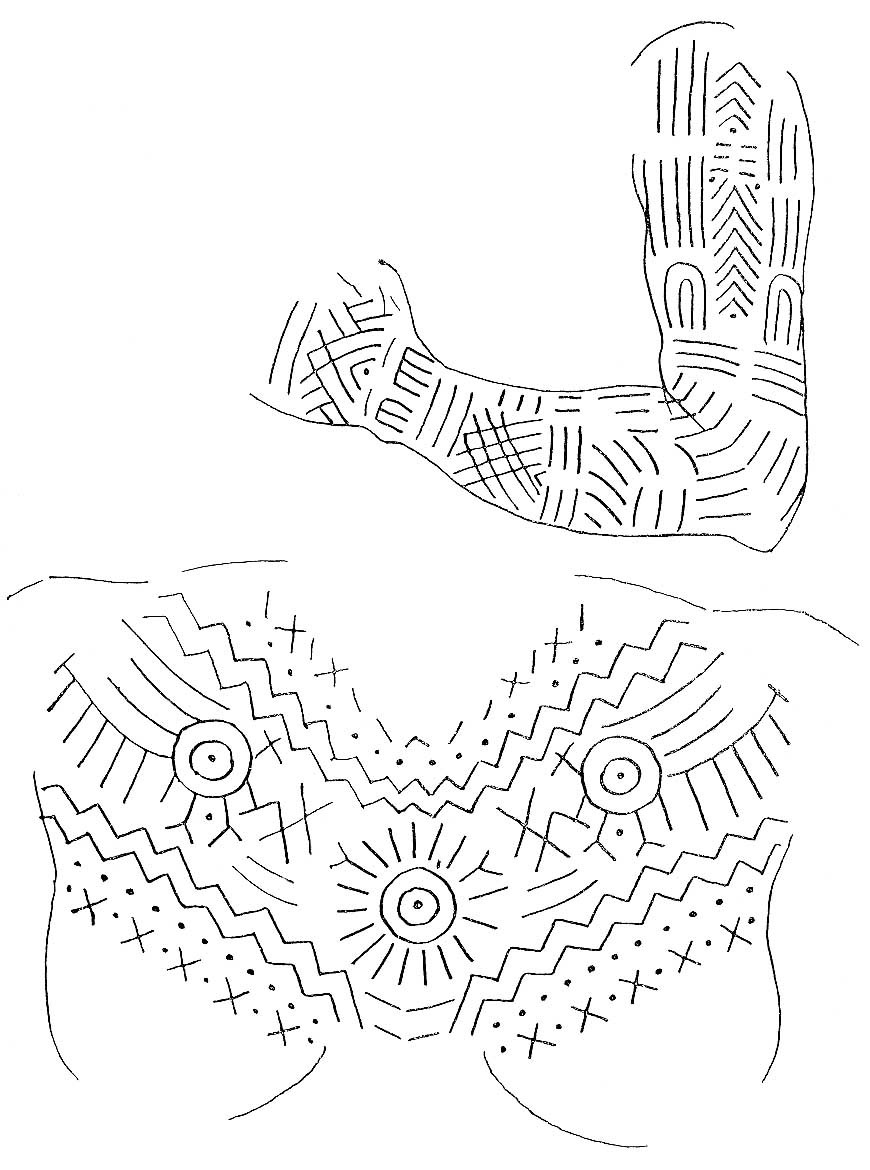

Bhumia body tattoos.

Bhumia body tattoos.

Baiga tattoos were applied by Badna caste tattooers (badnin or Godnaharin), still active at fairs and markets. Pigment was made from bhilawan tree juice or burnt snake skin mixed with black til (sesame) and ramtilla oil. Skin was pricked with needles and juice rubbed in. Modern tattooists use electric machines. After tattooing, the area was washed with cow dung water or soapnut liquid for cooling and pain relief. Soapnuts were also used as amulets for teething children.

Bhumia leg and thigh tattoos.

Bhumia leg and thigh tattoos.

Traditional tattooing was painful, lasting for days. Elders joked about enduring tattoo pain versus childbirth pain. Tattooing was avoided during monsoon season due to infection risks. Baiga women’s tattoos were considered sexually expressive and stimulating. A Baiga man remarked on the beauty of tattooed women, comparing them to bangles. Tattoos were seen as permanent adornment, lasting beyond death. Baiga beliefs included the idea that tattoos could be “sold” after death. The dhandha back tattoo, a six-dot riddle, was believed to persist into reincarnation.

.](https://i0.wp.com/www.larskrutak.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/DSC_6488-Edit-scaled.jpg)

Baiga men were traditionally forbidden from witnessing tattooing. Tattooed girls underwent two days of seclusion, covered in turmeric and oil, then bathed. Violations were believed to anger Bhagavan, the Supreme Deity. In the 1990s, Baiga women linked tattoos to health benefits like arthritis prevention, weather immunity, poison resistance, and blood disorder protection.

.](https://i0.wp.com/www.larskrutak.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/DSC_5656-Edit.jpg)

Baiga Forehead Markings and Tattoo Progression

Baiga girls around age eight received a “V” mark on their forehead, along with dots and lines. Tattooists were paid with turmeric, salt, chili, a coin wrapped in leaves, blessed the girl, and received payment. Puberty brought peacock or basket (dauri) tattoos on the breast and turmeric root (haldi-gāth) tattoos on the arm. Marriage brought jhophari patterns on the back of the hand and palāni or kajeri lines on thighs. Knees received phulia flower motifs, and backs were tattooed with flies, men, magic chains (sakri), and dhandha designs. Legs were tattooed with fishbones and steel (chakmak). Tattoo costs varied, increasing over time.

.](https://i0.wp.com/www.larskrutak.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/DSC_6769-Edit-scaled.jpg)

Muria Khond women were tattooed by female relatives or Ojha women. Ink was made from charcoal dust, incense, and til or mahua oil, burnt and scraped. Bamboo pens and needle instruments were used. Tattooists invoked the Seven Sisters of Bara Deo (Supreme Protector) before and during tattooing, sometimes singing songs like:

“Listen to our prayer. Yours is the promise we made that day. Let the burning of the needles cease.”

Payment included rice, turmeric, oil, chilies, and salt, waved around the tattooed girl in a cooling ritual.

.](https://i0.wp.com/www.larskrutak.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/DSC_6787-Edit-scaled.jpg)

Khond Ghat Tattoos and Magical Protection

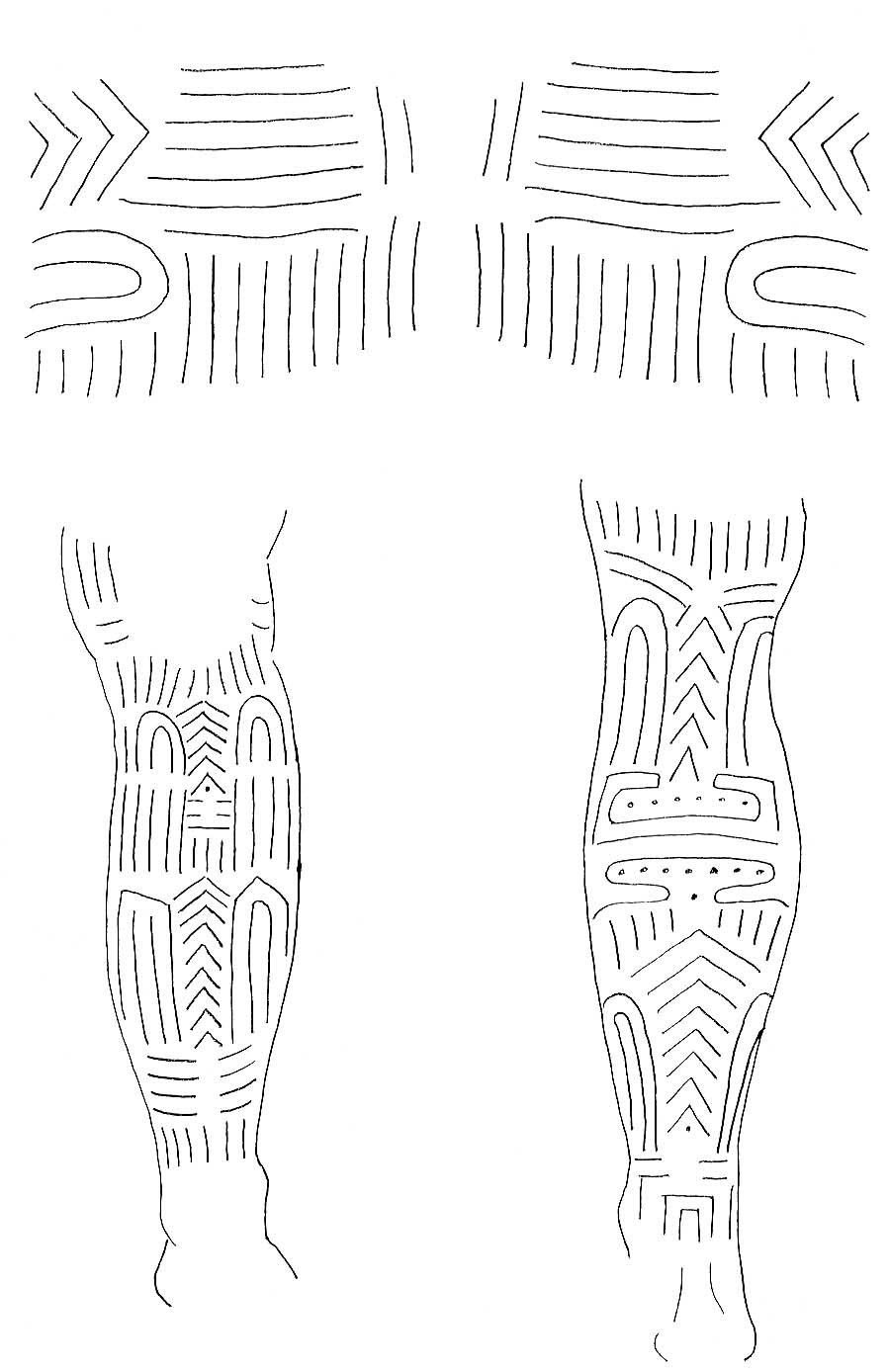

Khond women heavily tattooed their bodies, especially legs with parallel lines called ghats or “steps,” sometimes interspersed with sankal or “chain” designs, possibly for leg strength.

Khond ghat tattoos on legs. Khond Ghats

Khond ghat tattoos on legs. Khond Ghats

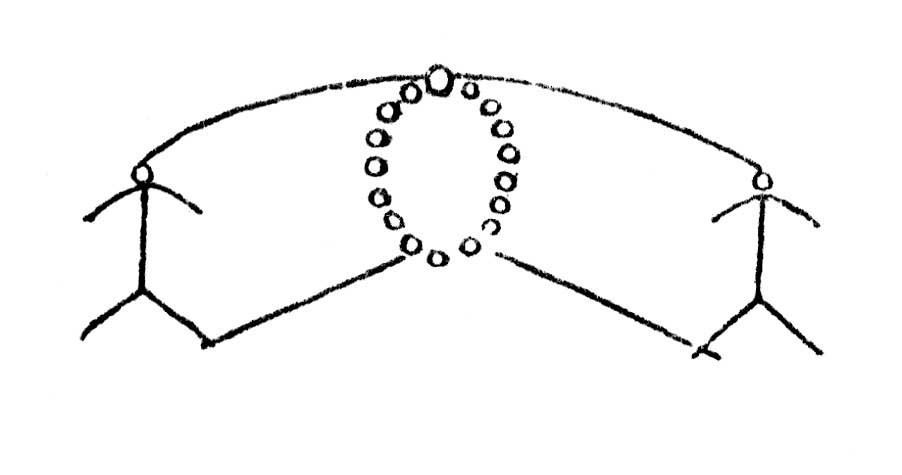

Khond, Bhumia, and Baiga tattooing was originally for magical protection, like talismans, and potentially totem identification. A Baiga priest (ca. 1915) explained tattoo meanings: triangular foot sole tattoos for earth protection, oval left sole tattoos for “Foot-God” Padam Sen Deo, toe and foot line tattoos for Elephant God Gajkaran Deo, back-of-leg tattoos for Baiga priests and priestesses for labor strength, horse tattoos on upper legs for Horse-god Koda Deo, Hanuman tattoos on upper arms for strength, back oblong tattoos for Bhimsen (cooking-place/rain god), Bara Deo tattoos on breast for child protection (after childbirth), and Kanteshwar Mata (necklace goddess) tattoos around the neck. Forehead tattoos of Chandi Mata (moon goddess) were for husband’s life protection, applied after marriage hair parting.

Bara Deo Tattoo.

Bara Deo Tattoo.

Origins of tattooing in Madhya Pradesh are linked to Bara Deo’s sons, Murha (Muria) and Ojha. Ojha’s wife learned tattooing, receiving divine protection from Bara Deo against evil magic during the practice. Bhumia women believed tattoos pleased Bhagavan in the afterlife. Muria Khonds saw tattoos as a “passport” to the afterlife, pleasing the Creator god Mahapurub. Sorcerers tattooed images of their deities for constant protection against evil magic.

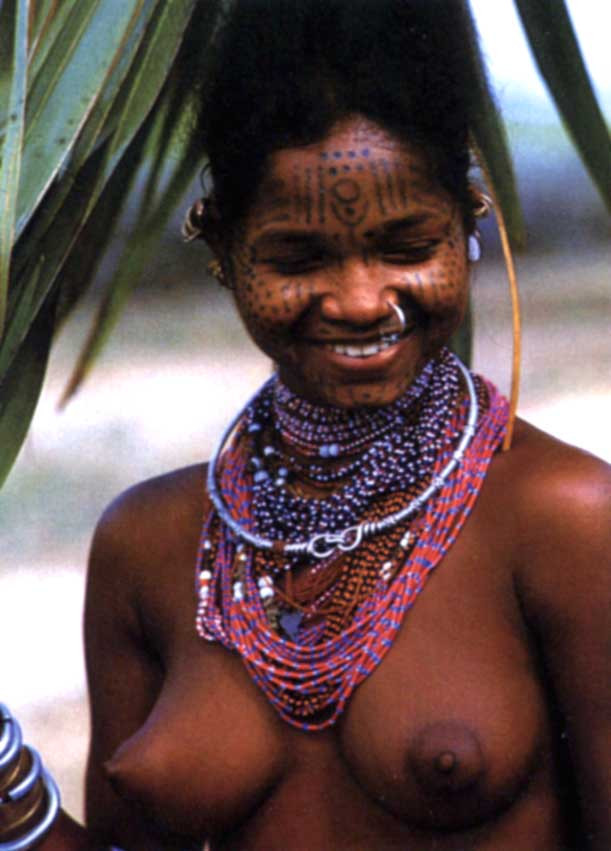

Kutia Khond woman of Orissa.

Kutia Khond woman of Orissa.

Gujarat: Mer and Rabari Tattoo Traditions

Gujarat tribes like the Mer believed tattoos, not wealth, were the true afterlife companions. A Mer proverb stated, “We may be deprived of all things of this world, but nobody has the power to remove the tattoo marks.” A Mer tattoo song echoed this sentiment.

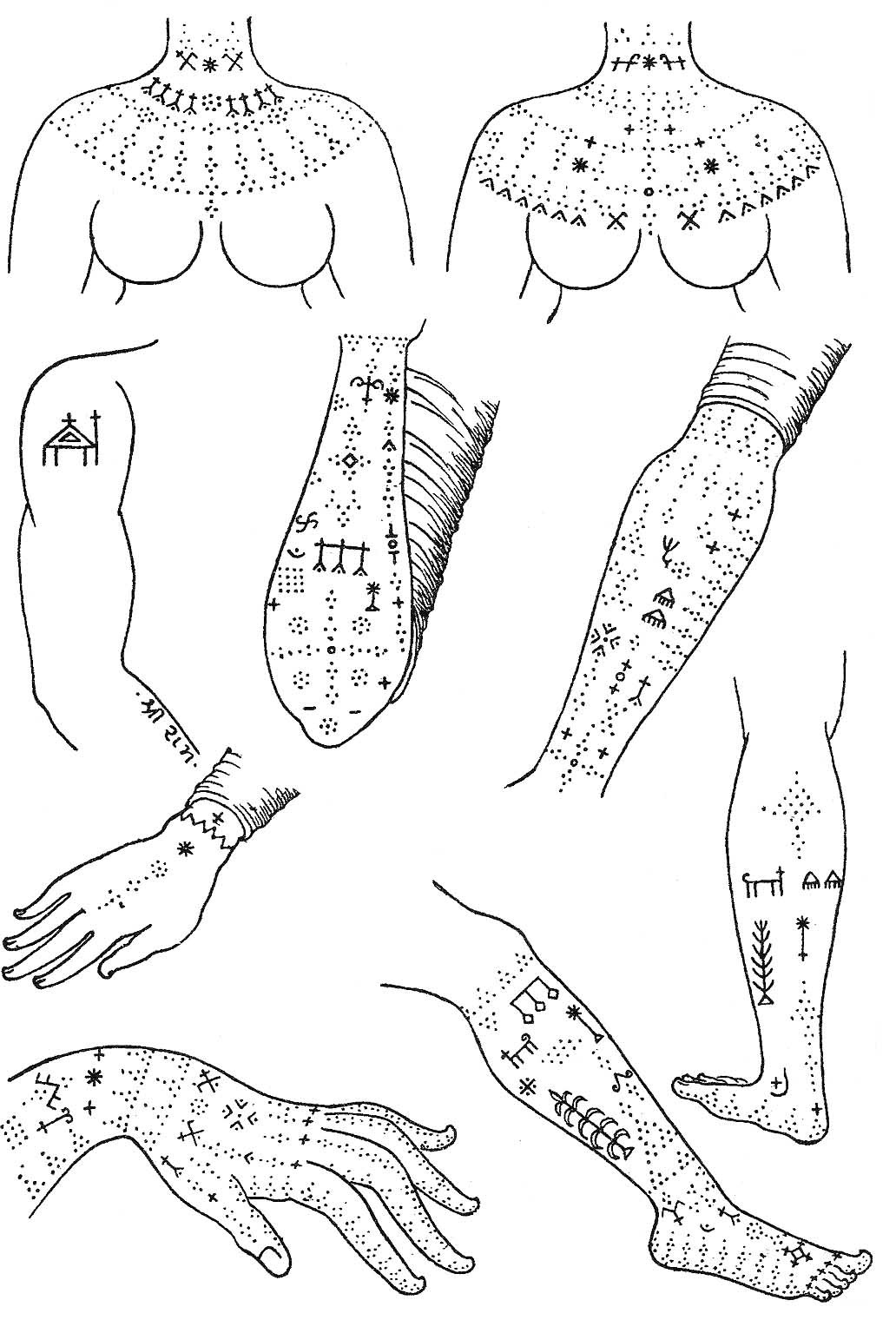

Mer body tattoos.

Mer body tattoos.

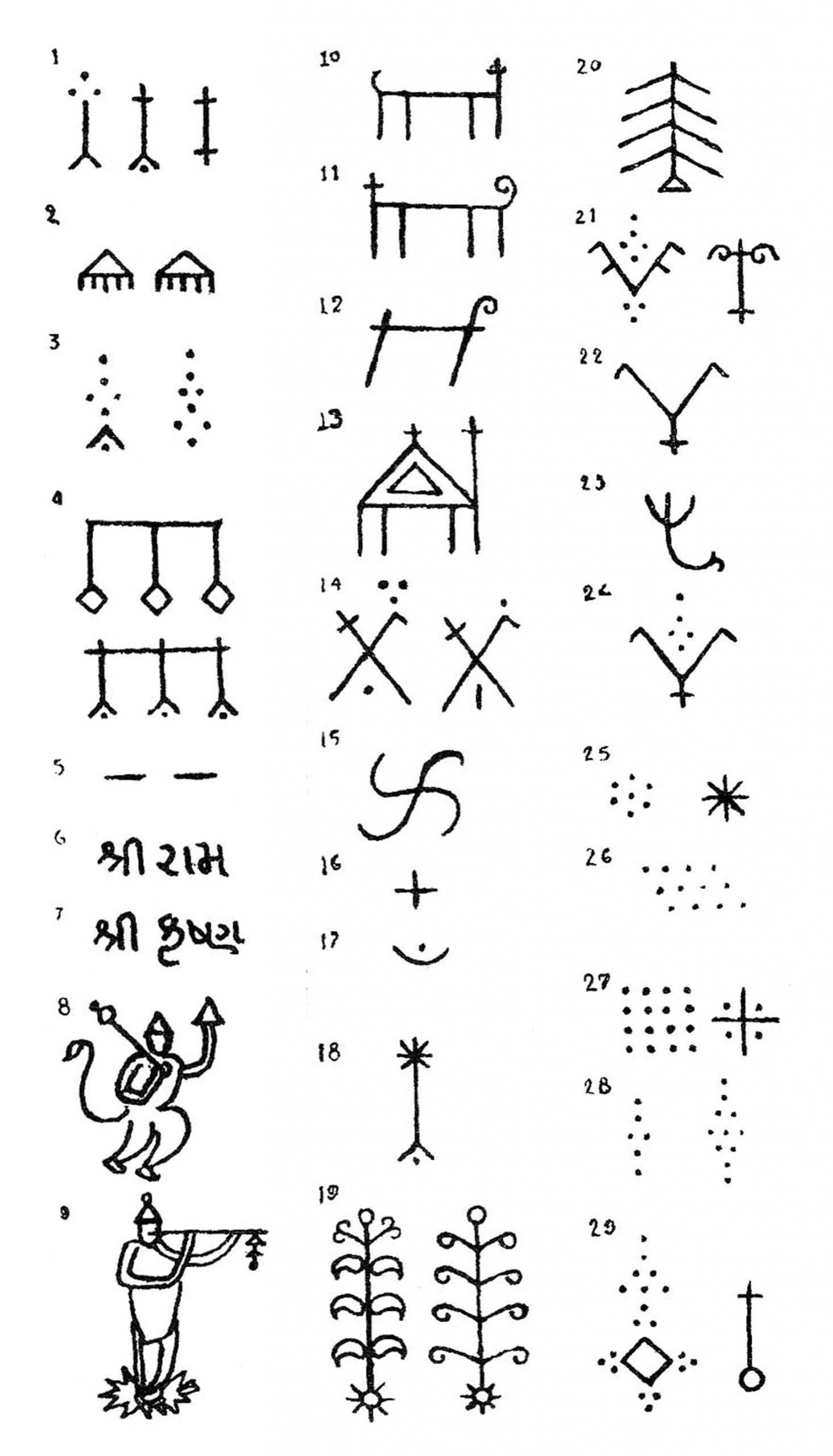

The Dangs shared this belief, fearing God’s red-hot ploughshare for the untattooed in the afterlife. Mer tattoo motifs included holy men, Rama and Lakshmi’s feet, women carrying water, Shravana carrying parents, and deities like Rama, Krishna, and Hanuman. Animals like lions, tigers, horses, camels, peacocks, scorpions, bees, and flies were popular, along with nature symbols (coconut, date palm, mango, acacia, champa flowers, almonds) and everyday objects.

Mer tattoo motifs: Mer tattoos: 1) Holy men, 2) Feet of Rama, 3) Pāniāri, 4) Kāvad, 5) Feet of Lakshmi, 6) Name of Rama, 7) Name of Krishna, 8) Hanuman, 9) Krishna, 10) Tiger, 11) Lion, 12) Horse, 13) Camel, 14) Peacock, 15) Scorpion, 16) Bee, 17) Fly, 18) Coconut tree, 19) Mango tree, 20) Date palm, 21) Large Bāval tree, 22) Small Bāval tree, 23) Champa flower, 24) Kevado plant, 25) Flower, 26) Almond nut, 27) Pedestal, 28) Yoke strap, 29) horse’s saddle bag.

Mer tattoo motifs: Mer tattoos: 1) Holy men, 2) Feet of Rama, 3) Pāniāri, 4) Kāvad, 5) Feet of Lakshmi, 6) Name of Rama, 7) Name of Krishna, 8) Hanuman, 9) Krishna, 10) Tiger, 11) Lion, 12) Horse, 13) Camel, 14) Peacock, 15) Scorpion, 16) Bee, 17) Fly, 18) Coconut tree, 19) Mango tree, 20) Date palm, 21) Large Bāval tree, 22) Small Bāval tree, 23) Champa flower, 24) Kevado plant, 25) Flower, 26) Almond nut, 27) Pedestal, 28) Yoke strap, 29) horse’s saddle bag.

Mer men had wrist, hand, and shoulder tattoos, often camels. Right-side tattoos in men may relate to the right hand’s importance in Hindu rituals. Hindu motifs like Rama, Krishna, Hanuman, and Om reflected Hinduization.

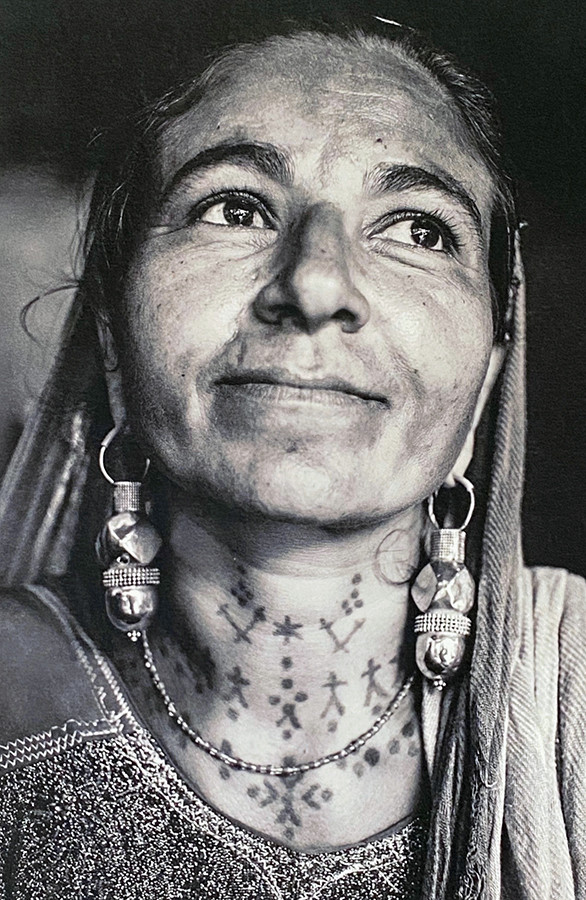

Tattooed Mer woman, Junaghad. Photograph © Shatabdi Chakrabarti.

Tattooed Mer woman, Junaghad. Photograph © Shatabdi Chakrabarti.

Mer girls were tattooed around seven or eight years old, starting with hands and feet, then neck and breast, ideally before marriage. Untattooed brides faced criticism from in-laws.

Tattooing tools were reed sticks with needles. Pigments were soot and cow urine/tulsi juice (blue-black/green) or red mercury oxide. The hānsali neck tattoo was a favorite, resembling a silver necklace, featuring flowers, peacocks, holy men, and deri (churning pot cover) motifs. Pāniāri (water pitcher) motifs adorned breasts and forearms. Legs were tattooed up to the knees with nature motifs. Pāniāri girdles on inner feet were considered charming. Mer women or wandering groups like Vāgharis and Nats were tattoo artists, paid in grain or cash. By the 1950s, men with machines were increasingly common.

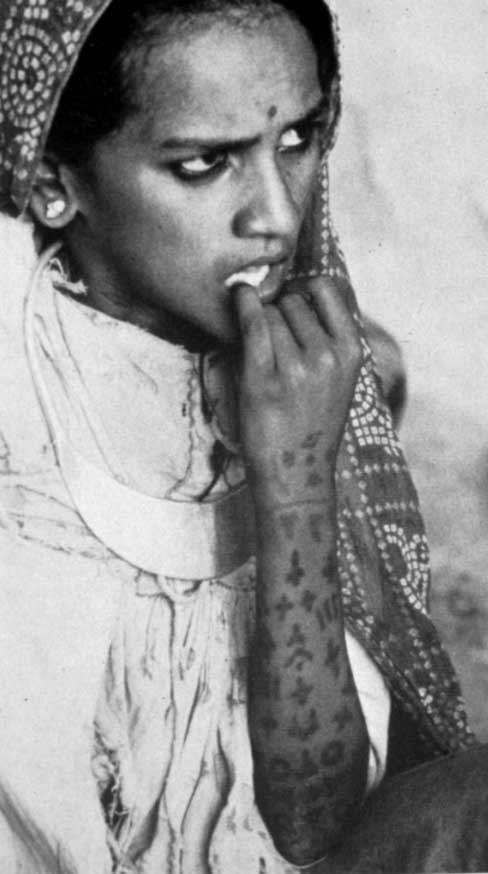

Tattooed Rabari woman.

Tattooed Rabari woman.

Rabari of Kutch also practiced tattooing, though younger urban women were adopting it less. Traditional trajuva patterns were passed down, with elder women tattooing at gatherings.

Rabari forearm markings.

Rabari forearm markings.

Rabari tattoo tools

Rabari tattoo tools

Pigment was lampblack with kino tree tannin, mother’s milk, or urine. Kits were simple: needle and gourd. Bodies were extensively tattooed: face, neck, breasts, arms, hands, legs, feet. Some Kutch tattoos were caste marks, others for fertility or attracting husbands, and nature-inspired motifs for protection. Many Rabari motifs mirrored Mer designs in form and meaning.

Naga and Arunachal Pradesh: Warrior Tattoos and Tribal Identity

The Naga ethnic groups of Northeast India and Northwest Myanmar migrated around A.D. 400, settling in mountainous terrain. Formerly headhunters (outlawed in 1953), they maintained animistic beliefs focused on unseen powers. Tattooing was widespread, now rare, but well-documented from the 1920s-30s.

Among Ao Naga, tattoo artists were elderly women, operating in the jungle during December and January. Tattoo knowledge was hereditary in the female line.

Tattoo style of the Ao Naga Chungli subgroup.

Tattoo style of the Ao Naga Chungli subgroup.

Girls were tattooed pre-puberty for social acceptance and marriage prospects. During tattooing, girls were held down on bamboo mats, while the tattooist used cane thorns on wooden holders, hammered with a kamri root. Patterns were marked with wood and dye from napthi tree bark soot. Screaming during tattooing led to fowl sacrifice to appease spirits.

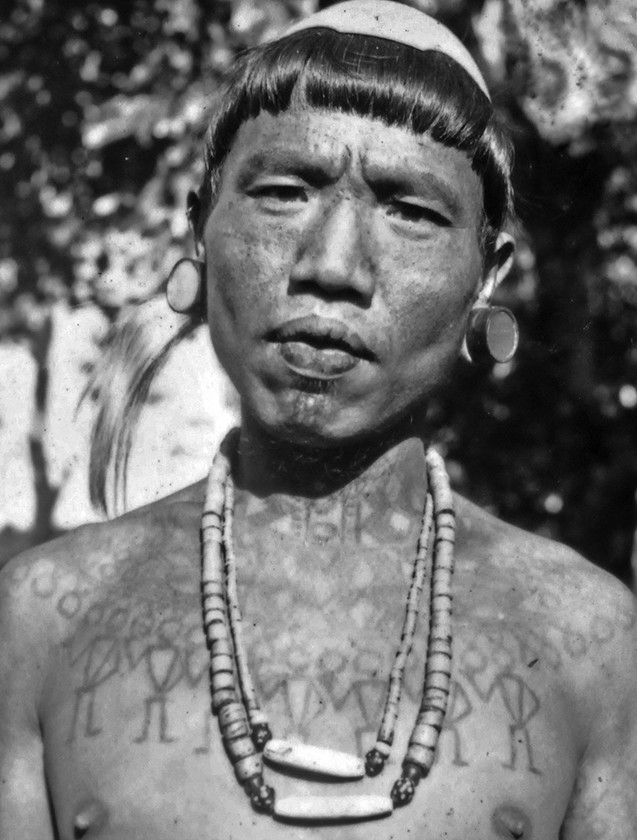

Among Konyak, young men were ceremonially tattooed after participating in headhunting, a sign of manhood and magical power. Tattooing was performed by the chief’s principal wife, taking a full day for one face. Veteran warriors earned neck and chest tattoos for multiple kills.

Konyak tattooist hand-tapping a girl’s legs. 1936. Photograph by Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf.

Konyak tattooist hand-tapping a girl’s legs. 1936. Photograph by Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf.

Konyak Warrior Tattoo

Konyak Warrior Tattoo

Headhunting rituals included egg smashing and rice beer libations on enemy heads, skull feeding ceremonies, and head display on log drums. Heads were then kept in clan morung (men’s house). Even after headhunting bans, Konyak continued tattooing rituals with substitutes like monkey skulls. Facial tattooing is now rare among younger Konyak and Wancho men.

The late Konyak warrior Lanang of Longwa village which straddles the Myanmar border. His goggle-like facial markings denote his participation in hand-to-hand combat, and the V-shaped chest tattoos were earned for dispatching two enemies. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

The late Konyak warrior Lanang of Longwa village which straddles the Myanmar border. His goggle-like facial markings denote his participation in hand-to-hand combat, and the V-shaped chest tattoos were earned for dispatching two enemies. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

The former Konyak warrior and gaonbura (village headman) Nokngam of Shangnyu village, Nagaland. His faded W-shaped chest motifs were given after initiation into the men’s house (paan), and the facial tattooing after participation in first combat. His neck tattoos (ding hu) were earned for head-taking in his youth and established his identity as a great warrior (naomei). Stylistically, neck tattoos were composed of subtle yet distinctive design elements that varied across Konyak villages; they could be read by others and identified the man thus marked. When this photograph was taken, Nokngam was the only tattooed warrior of the naomei class still living in Shangnyu. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

The former Konyak warrior and gaonbura (village headman) Nokngam of Shangnyu village, Nagaland. His faded W-shaped chest motifs were given after initiation into the men’s house (paan), and the facial tattooing after participation in first combat. His neck tattoos (ding hu) were earned for head-taking in his youth and established his identity as a great warrior (naomei). Stylistically, neck tattoos were composed of subtle yet distinctive design elements that varied across Konyak villages; they could be read by others and identified the man thus marked. When this photograph was taken, Nokngam was the only tattooed warrior of the naomei class still living in Shangnyu. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Chang and Phom Naga men had different tattooing. Boys in war parties but not in battle had ear piercings. Head-takers received chest tattoos described as “ostrich feathers,” “V-shaped,” “fertility fountain,” or “tiger chest” by Khiamniungan, believing they became “tiger-like.” Human figure tattoos were added for more kills. Arms, shoulders, calves, and backs were also tattooed.

Former Phom Naga warrior Eno Henham Buchemhü of Yongshei village, Nagaland. Over the past century, writers have described the broad V-shape style chest tattooing of Phom, Chang, and some neighboring Konyak villages as “ostrich feathers” or a “fertility fountain.” Neither of these explanations are correct and Phom warriors have told me they symbolize the horns of a mithun, a sacred semi-domesticated bovine. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Former Phom Naga warrior Eno Henham Buchemhü of Yongshei village, Nagaland. Over the past century, writers have described the broad V-shape style chest tattooing of Phom, Chang, and some neighboring Konyak villages as “ostrich feathers” or a “fertility fountain.” Neither of these explanations are correct and Phom warriors have told me they symbolize the horns of a mithun, a sacred semi-domesticated bovine. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Chang women were only face-tattooed, mostly foreheads, believed to scare tigers. One village’s forehead tattoo was linked to a maiden’s sacrifice to stop a flood. Other Naga groups believed forehead tattoos aided ancestor recognition or served as afterlife currency. Abor of Arunachal Pradesh shared similar beliefs.

Chellia, a great Khiamniungan warrior of Noklak village, Nagaland, who tallied eight human kills during his military career. The tattooed anthropomorphs symbolize some of his victims, and his arm tattoos represent “the path of the tiger.” The V-shaped chest motif signifies the “tiger chest.” Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Chellia, a great Khiamniungan warrior of Noklak village, Nagaland, who tallied eight human kills during his military career. The tattooed anthropomorphs symbolize some of his victims, and his arm tattoos represent “the path of the tiger.” The V-shaped chest motif signifies the “tiger chest.” Photograph © Lars Krutak.

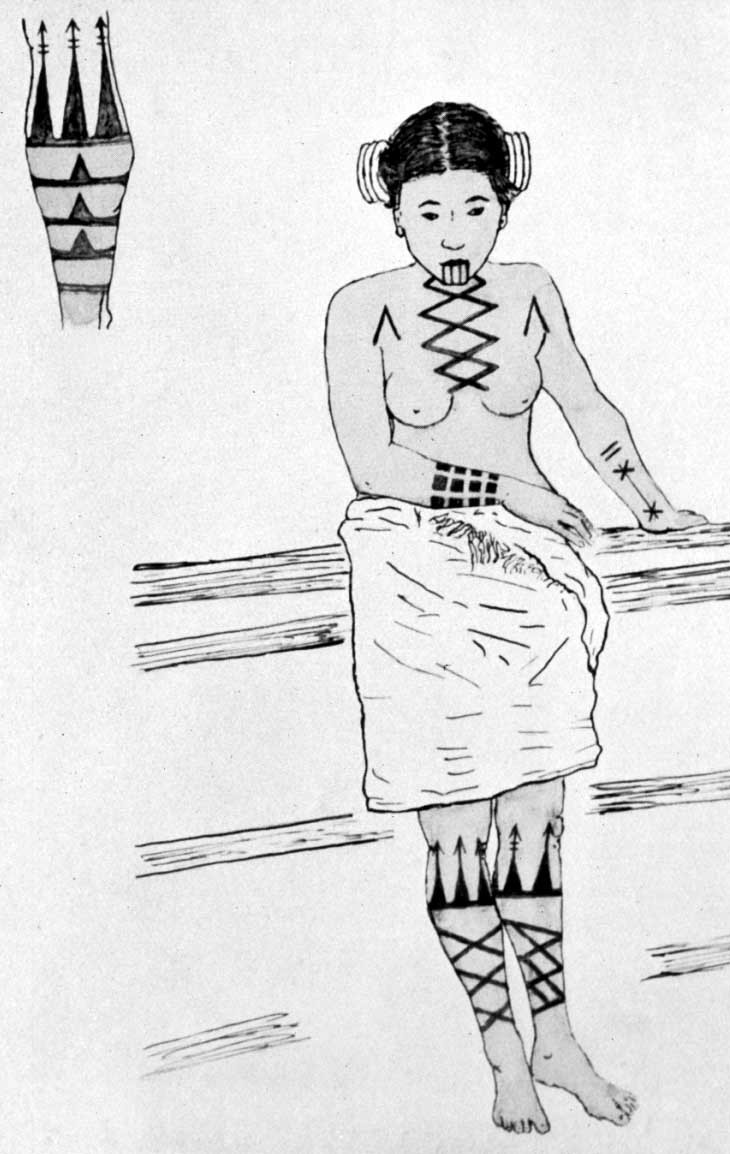

Wancho Naga women lacked face tattoos but had extensive body tattoos with social and ritual significance. Designs varied by social status, with chiefly families having elaborate tattoos. Tattoos marked life stages: puberty, marriage, pregnancy.

Wancho navel tattooing illustrates the social status of the bearer. Queens (anghya) possessed /// marks at the terminus of each tattooed line. Common women, like Wancho elder Apu Wangsni of Nianu village, Arunachal Pradesh, do not have such lines.

Wancho navel tattooing illustrates the social status of the bearer. Queens (anghya) possessed /// marks at the terminus of each tattooed line. Common women, like Wancho elder Apu Wangsni of Nianu village, Arunachal Pradesh, do not have such lines.

First tattoos (chung hu) were navel crosses at ages six to seven. Puberty brought calf and leg tattoos. Marriage brought thigh tattoos. Chest tattoos, resembling “M” shapes, came in the seventh month of pregnancy or after the first child. Aristocratic women had more elaborate designs, including arm and shoulder tattoos.

Phekhaw Wangcha, a Wancho queen and former tattooist of Nianu village, Arunachal Pradesh, wears special tattoo leg motifs consisting of various XXX, diamond, and Y-form patterns that only women of her social status can own. Her turquoise color beads also indicate her high rank. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Phekhaw Wangcha, a Wancho queen and former tattooist of Nianu village, Arunachal Pradesh, wears special tattoo leg motifs consisting of various XXX, diamond, and Y-form patterns that only women of her social status can own. Her turquoise color beads also indicate her high rank. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Wancho tattooing tools were similar to Ao Naga. “Tattoo Queens” (chief’s wives) were tattoo artists, after divination rituals and feasts. Pigment was soot, pine resin, and water. Skin was stretched during tattooing. Bluish plant juice enhanced color and healing. Payment included pig legs, rice, and zu (rice beer).

Wancho woman of Nianu village displaying the chest tattoo that is given after a girl has wed. The anghya of the village bears a slightly different style which is more V-shaped in form. I was told the motif represents an anthropomorphic being and no further information was given regarding its origin or meaning. Nianu village, Arunachal Pradesh. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Wancho woman of Nianu village displaying the chest tattoo that is given after a girl has wed. The anghya of the village bears a slightly different style which is more V-shaped in form. I was told the motif represents an anthropomorphic being and no further information was given regarding its origin or meaning. Nianu village, Arunachal Pradesh. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Wancho men earned tattoos through headhunting, tattooed by the Queen. Facial tattoos (thun hu) were prestigious warrior marks, with leg tattoos for taking hands or feet. Chest tattoos and brass ornaments symbolized kills. Tiger slayers could also earn tattoos. Warrior tattooing followed kills by days, performed by the Queen. Extensive tattoos signified prowess. Warriors observed post-tattooing taboos.

Tattooing was an expensive undertaking among the Wancho Naga, unless you were a member of the royal family and paid no fee. However, the former warrior Langtun Lukham of Nianu village paid a pig’s leg and a quantity of rice beer (zu). He received his tattoo for participating in a successful headhunting raid and his chest tattoo was completed in one day. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Tattooing was an expensive undertaking among the Wancho Naga, unless you were a member of the royal family and paid no fee. However, the former warrior Langtun Lukham of Nianu village paid a pig’s leg and a quantity of rice beer (zu). He received his tattoo for participating in a successful headhunting raid and his chest tattoo was completed in one day. Photograph © Lars Krutak.

Wancho headhunters once displayed neck tattoos and human figures that tallied their victories on the battlefield. Photograph by Verrier Elwin. Courtesy of Ashok Elwin.

Wancho headhunters once displayed neck tattoos and human figures that tallied their victories on the battlefield. Photograph by Verrier Elwin. Courtesy of Ashok Elwin.

India: A Land Etched in Eternal Ink

From Naga warrior tattoos to magical kolam and Hindu pantheon designs, Indian tattoo cultures present a rich and diverse visual art form spanning millennia. While modernity and Western influences bring transformations, vestiges of indigenous tattooing persist, revealing deep cultural integration with human, spiritual, and environmental worlds. Tattooing defined identity, maturity, social roles, and artistic expression. Though modern Indian youth increasingly favor Western tattoo styles, the legacy of traditional Indian Tattoos remains a vital part of India’s cultural heritage, deserving continued attention and appreciation.

Literature

Chowdury, J.N. (1992). Arunachal Panorama. Itanagar: Directorate of Research.

Fischer, E. and H. Shah (1973). “Tatauieren in Kutch.” Ethnologische Zeitschrift Zurich 11: 105-129.

Fuchs, S. (1968). The Gond and Bhumia of Eastern Mandla. Bombay: New Literature Publishing House.

Ganguli. M. (1984). A Pilgrimage to the Nagas. New Delhi: IBH Publishing.

Gell, A. (1998). Art and Agency. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gupte, B.A. (1902). “Notes on Female Tattoo Designs in India.” The Indian Antiquary 33: 293-297. July.

Iyer, D.B.L.K.A. (1935). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. 1. Mysore: The Mysore University.

Laukien, M. (2005). “Tattooing in India – The Continent of Body Art.” Skin and Ink Magazine (6) 58-76. June.

Layard, J. (1937). “Labyrinth Ritual in South India: Threshold and Tattoo Designs.” Folklore 48: 115-182.

Leuva, K.K. (1963). The Asur: A Study of Primitive Iron-Smelters. New Delhi: Bharatiya Adimjati Sevak Sangh.

Mills, J.P. (1926). The Ao Nagas. London: MacMillan & Co.

Rao, C.H. (1946). “Note on Tattooing in India and Burma.” Anthropos 37: 175-179.

Rose, H.A. (1902). “Note on Female Tattooing in the Panjab.” The Indian Antiquary 33: 297-298. July.

Roy S.C. and R.C. Roy (1937). The Khāriās. Ranchi: “Man In India” Office.

Rubin, A. (1988). “Tattoo Trends in Gujarat.” Pp. 141-153 in Marks of Civilization (A. Rubin, ed.). Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History.

Russell, R.V. and R.B.H. Lāl (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India. Vol. III. London: MacMillan and Co.

Thurston, E. (1898). “Note on Tattooing.” Madras Government Museum Bulletin 2(2) 115-119.

____(1906). Ethnographic Notes in Southern India. Madras: Government Press.

Trivedi, H.R. (1952). “The Mers of Saurashtra: A Study of Their Tattoo Marks.” Maharaja Sayajirao University Journal 1(2): 121-131.

Verrier, E. (1939) The Baiga. London: John Murray.

___(1991). The Muria and Their Ghotul. Bombay: Oxford University Press.